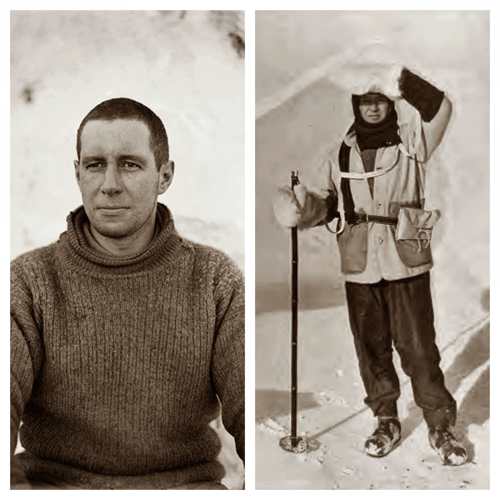

Apsley Cherry-Garrard faced death. He thought about lost chances and missed paths. “Men don’t fear death,” he wrote, “they fear the pain of dying.” In his despair, he considered overdosing on morphine. Yet, he craved something simple: tinned peaches in syrup. These thoughts often fill the minds of those nearing the end.

The blizzard raged at force twelve, the highest level on the storm scale. They lost their tent on July 22nd and the igloo roof the next day. Snow buried them, and they hadn’t eaten for thirty-six hours. On Monday, the storm eased slightly. They crawled out from under the snow and rocks, managed to light a stove, and melted snow. They boiled pemmican and made tea, albeit with penguin feathers and dirt. Surprisingly, it was the best meal they had ever had.

Afterward, they searched for anything salvageable. ‘Birdie’ Bowers found the tent, half-buried in a snowdrift. It had snapped shut like an umbrella, saving it from being blown away. They set it up again, securing it better than ever before. They debated their next move. Bowers wanted to hunt penguins again, and Cherry agreed. However, Wilson suggested they return to McMurdo Sound. They packed what they could onto one sled and left the other behind, marked with a note.

The return journey was just as brutal. Bowers fell into a crevasse, and Cherry and Wilson struggled to pull him out. Their sleeping bags, clothes, and tent froze solid. Despite the exhaustion, they trudged on, frostbitten and weary, often dozing off while walking. They finally reached Hut Point at Cape Armitage, where they found more fuel oil, two stoves, and cocoa. They feasted on the supplies.

The next day, they pushed hard for Cape Ross, arriving at 11 PM on August 1st. They had been gone for thirty-six days and traveled sixty-seven miles. Cherry-Garrard wrote, “… ended the worst journey in the world.”

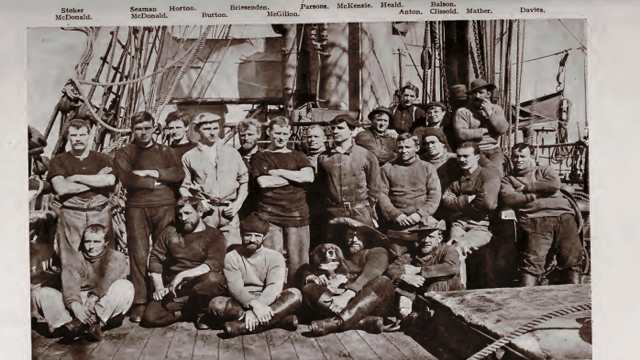

Captain Scott noted in his journal on August 2nd that the Crozier Party returned after five weeks of extreme hardship. They looked worn and weathered, their faces scarred, but remarkably few had frostbite. Their main issues stemmed from lack of sleep. After a good rest, they appeared much better.

Cherry wrote that once they were freed from their frozen clothes, they slept for what felt like an eternity. They quickly recovered, though Cherry lost some toenails and had a blister on his heel. By October 1911, they were fit enough to join Scott’s push for the South Pole.

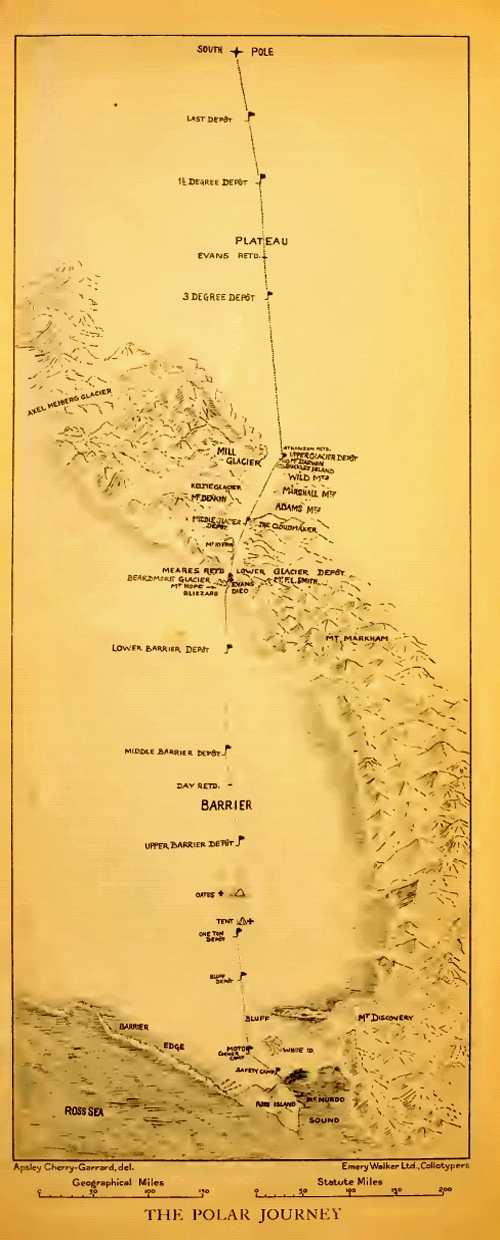

The expedition began with a Motor Party carrying supplies, but both sledges broke down after 50 miles. The four-man team had to carry a 740-pound load for 150 miles to latitude 80° 30′ South. On November 21st, three other teams joined them, and they continued to the Beardmore Glacier with ponies and dogs. A blizzard in early December halted their progress. The exhausted ponies were shot, and the dogs were sent back.

After climbing the glacier and reaching the polar plateau, some, including Cherry, returned to Cape Evans. Scott, Wilson, Bowers, Lawrence ‘Titus’ Oates, and Edgar Evans pressed on for the Pole. They reached the South Pole on January 17th, 1912, only to find that Norwegian Roald Amundsen had arrived thirty-three days earlier. Scott described the Pole as “an awful place.”

Meanwhile, those who returned earlier set out to create supply depots for the returning party. Cherry and dog-handler Dmitri Gerov supplied the One Ton Depot in late February 1912. They waited for Scott’s team until March 10th, when their dog supplies ran low.

Scott’s team began their return from the Pole on February 7th, facing poor conditions. Oates suffered from frostbite, and Evans was in bad shape with injuries. On February 17th, Evans collapsed and died at the glacier’s base. Around March 17th, Oates calmly told Scott, “I am just going outside and I may be some time,” before walking out into the storm.

A blizzard trapped them just eleven miles from One Ton Depot. As supplies dwindled, their situation worsened. Scott’s diary entry from March 29th, 1912, read: “Every day we have been ready to start for our depot, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, and the end cannot be far.”

Back at Cape Evans, acting commander Edward Atkinson feared for Scott’s safety. He set out with a relief party but was turned back by bad weather. In October, he led another party south and found the bodies of Scott, Wilson, and Bowers in their tent. They also found Oates’s sleeping bag but not his body.

The Terra Nova returned to New Zealand in February 1913. Cherry’s health declined after returning to England. He suffered from depression, irritable bowel syndrome, and what we now call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. To cope, he wrote a two-volume account of the expedition, titled The Worst Journey in the World (1922). National Geographic Magazine later voted it the greatest true adventure book ever written.

Cherry was haunted by the loss of Scott and the Polar party for the rest of his life. He felt guilty for not doing more when he was at One Ton Depot. He regretted not going on with the dogs to meet them, just eleven miles away.

As for the Emperor Penguin eggs, Cherry delivered them to the Natural History Museum in 1913. He faced an unhelpful caretaker who referred him to the Chief Custodian of Eggs. After some insistence, he received a receipt for the eggs. Later, when Scott’s sister asked to see them, she was told they didn’t exist. She threatened to expose the situation, leading to a letter revealing the eggs had been passed to Professor Assheton for examination, but he died before starting the work. The eggs then went to Professor Cossar Ewart, who concluded that the journey was not in vain.

In 2007, the BBC produced a docudrama titled The Worst Journey in the World, starring Mark Gatiss as Cherry-Garrard. The Cape Crozier igloo was rediscovered by the Fuchs-Hillary Trans-Antarctic expedition in 1957-58.

Cherry married Angela Turner in 1939 but chose not to have children due to fears of inherited mental illness. He passed away on May 18th, 1959. He once said, “If you have the desire for knowledge and the power to give it physical expression, go out and explore.” His journey remains a testament to human endurance and the quest for knowledge.