Exploring Victorian Art and the Interplay of Science and Faith

In a quiet corner of a study, a painting hangs that captures a moment frozen in time: William Dyce’s “Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th, 1858,” more commonly referred to simply as “Pegwell Bay.” Completed by 1860, this masterpiece offers more than just a glimpse of a family’s day at the seaside—it’s a profound meditation on time, science, faith, and the fragile nature of existence.

This article explores how Dyce’s work encapsulates the era’s shifting views and scientific discoveries that challenged long-standing beliefs.

A Closer Look at William Dyce’s Background and Influences

William Dyce, born in Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1806, was a key figure in Victorian art. He studied painting at the Royal Academy schools and spent time in Rome, where he met Friedrich Overbeck and the Nazarenes—a group of 19th-century German artists who sought a return to the spirituality of early Christian art. The Nazarenes’ ideals significantly influenced Dyce, helping shape the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848, a group that aimed to defy conventional artistic norms and embrace meticulous attention to detail and nature. Dyce’s work, characterized by his detailed and careful observations, is seen as a precursor to the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and “Pegwell Bay” is a shining example of this.

The Scene at Pegwell Bay: More Than Meets the Eye

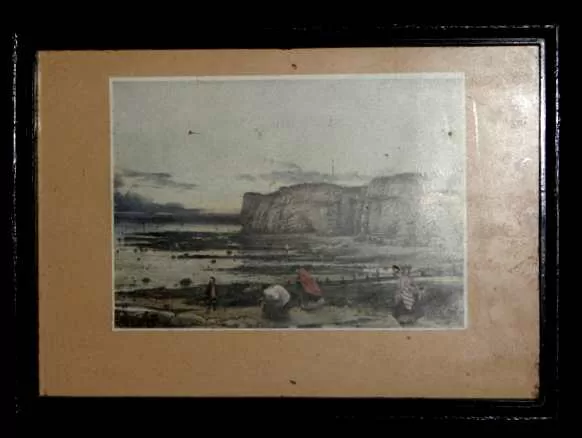

At first glance, “Pegwell Bay” appears to be a simple family scene. In the foreground, Dyce’s wife, her two sisters, and his son collect seashells while fishermen with shrimping nets and donkeys dot the background. However, Dyce’s painting goes beyond a mere family outing. The sky darkens as evening sets in, casting a somber tone that suggests the inevitable passage of time. But the real focal point of the painting is the faint streak of a comet—Donati’s Comet—visible in the twilight sky. This rare celestial event was first observed in June 1858 and was the second brightest comet of the 19th century. Its appearance in the painting marks a specific historical moment, drawing attention to the vastness of time and space.

Time, Impermanence, and the Symbols of Nature

The cliffs in the background, meticulously depicted with visible strata of rocks, flints, and fossils, tell their own story of Earth’s deep history. These elements symbolize the slow but constant process of erosion, change, and the inexorable march of time. Fossil hunting and seashell collecting were popular Victorian pastimes, capturing the public’s fascination with natural history. Dyce’s attention to these details highlights the impermanence of life and the continuity of nature’s cycles.

The inclusion of Donati’s Comet against the darkening sky serves as a powerful reminder of humanity’s fleeting existence in the grand scheme of the cosmos. As the comet blazes across the sky, it underscores the depth and immensity of space—a universe that exists far beyond human comprehension and control.

Victorian Science vs. Faith: A Crisis of Belief

The mid-19th century was a time of great scientific discovery and, consequently, profound existential crisis for many. Advances in geology, like those of Scotsman James Hutton, introduced the concept of ‘deep time,’ revealing that the Earth was much older than previously thought. His ideas were popularized by John Playfair and Charles Lyell, whose works directly influenced Charles Darwin during his voyage on the HMS Beagle. Darwin’s groundbreaking publication, “On the Origin of Species” (1859), which emerged around the time Dyce was working on “Pegwell Bay,” further eroded the traditional understanding of nature as God’s unchanging creation.

The discoveries of fossils, such as those unearthed by Mary Anning, also challenged the notion of a perfect, unchanging world. They served as undeniable evidence that entire species had gone extinct long before humanity’s existence, casting doubt on the concept of divine design. The tension between new scientific evidence and established religious beliefs led to a broader intellectual and spiritual conflict during the Victorian era.

Pegwell Bay’s Symbolism: The Tide of Faith

The symbolism of Pegwell Bay’s location adds another layer to Dyce’s message. Pegwell Bay sits near Ebbsfleet, the landing place of St. Augustine, who brought Christianity to England in the 6th century. Dyce’s choice of setting subtly suggests that just as the cliffs erode and the tide ebbs and flows, so too does faith shift and change over time. This theme echoes the sentiments of Victorian poet Matthew Arnold in his famous work “Dover Beach,” which laments the retreat of the “Sea of Faith” in the face of modernity.

Arnold’s words resonate with the painting’s overall atmosphere, capturing a moment when faith, once as solid as the cliffs themselves, appears to be withdrawing like the tide. Dyce’s depiction of this specific location hints at the cyclical nature of belief and the human struggle to reconcile new scientific understandings with deeply ingrained spiritual convictions.

Art Reflecting the Human Condition

“Pegwell Bay” remains a profound piece of art that captures the Victorian era’s anxieties and hopes. Dyce’s meticulous attention to detail, combined with his ability to weave a complex narrative about time, nature, and belief, makes this painting not just a family portrait but a powerful commentary on the human condition. The presence of Donati’s Comet reminds us that while scientific discovery can illuminate our understanding of the universe, it also challenges us to reconsider our place within it.

In essence, William Dyce’s “Pegwell Bay” stands as a timeless reflection of the struggle between old and new beliefs, the passage of time, and the enduring impact of scientific advancement on the human psyche. It invites viewers to look closer, not just at the painting, but at the broader questions it raises about our world, our history, and our future.