Absinthe, known as the Green Fairy, has long been shrouded in mystery, controversy, and myth. From the salons of 19th-century Paris to the bohemian circles of artists and poets, absinthe earned a notorious reputation as a hallucinogenic, brain-rotting elixir that fueled creativity and madness alike. But how much of this reputation is real, and how much is just hype?

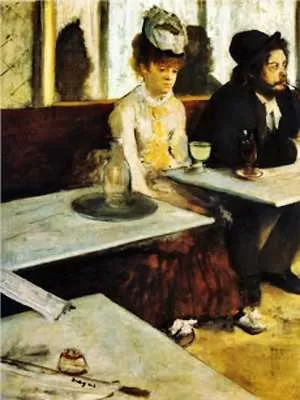

Absinthe first gained popularity in the late 18th century and quickly became the drink of choice for famous artists and writers, including Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, and Oscar Wilde. Its vibrant green color and ritualistic preparation method made it a favorite among the avant-garde, who saw it as a symbol of rebellion and artistic freedom. However, the drink’s rise in popularity came with tales of visions, hallucinations, and even madness, cementing its dark allure.

The most infamous event linked to absinthe occurred in 1905 when Swiss laborer Jean Lanfray murdered his family after drinking absinthe. Outrage followed, leading to calls for a ban. However, Lanfray had also consumed an excessive amount of other alcohol, including wine, brandy, and crème de menthe, yet absinthe took the blame. Soon after, bans swept across Switzerland, France, the U.S., and other countries, though curiously, the UK did not follow suit.

The primary ingredient blamed for absinthe’s supposed mind-altering effects is thujone, a compound found in wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), one of absinthe’s key ingredients. Thujone was believed to be a hallucinogen, though modern research has debunked this myth. Thujone also appears in common herbs like sage and tansy, as well as everyday products like vapour rubs, without causing any hallucinogenic effects. At high levels, thujone can cause muscle spasms, but the amount present in absinthe is not enough to have significant effects on the human brain.

Despite the bans, anise-flavored spirits like pastis emerged as alternatives. Developed by Paul Ricard in 1932, pastis contains similar flavors to absinthe but without wormwood. Absinthe and pastis both turn cloudy when water is added—a phenomenon called la louche—but only absinthe carries the historical stigma of the Green Fairy.

Today, absinthe is experiencing a renaissance. Countries have lifted bans, and it is no longer viewed as a dangerous or forbidden drink. Studies have shown that absinthe is no more harmful than any other alcoholic beverage, and thujone is not chemically related to THC, the active component in cannabis, as was once thought. Instead, absinthe’s notorious reputation stemmed largely from exaggerated claims, moral panic, and the desire of some drinkers to seem edgy or artistic.

Preparing absinthe involves pouring a measure of the spirit into a glass and slowly adding iced water until it reaches a cloudy green hue. Traditionally, sugar may be dissolved into the drink using a special slotted spoon, though the more theatrical practice of lighting the sugar on fire is a modern and inaccurate twist. Collectors today still seek vintage absinthe paraphernalia, like branded carafes and specialized glasses, embracing the ritual and romance of the Green Fairy while leaving the myths behind.

The truth about absinthe is far less dramatic than the legends suggest. It remains an iconic and misunderstood spirit, woven into the fabric of art, culture, and history—its allure enduring, but its dangers greatly exaggerated.