Tin boxes might seem like simple storage solutions today, but their history is steeped in the curious world of science, exploration, and debate. A decorative tin box, much like the one used for storing pens and pencils, connects us to stories of natural history, scientific discoveries, and the clash of ideas from the Renaissance to the early modern era. This tale involves some of the greatest thinkers of the past, including Aristotle, Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, and Thomas Jefferson, each challenging and reshaping our understanding of the natural world.

The Rise of Empirical Science and the Fall of Ancient Wisdom

The Renaissance was an age of questioning and rediscovery. With the growth of empirical science, scholars began to scrutinize ancient texts, finding that the “wisdom of the ancients” didn’t always align with observed reality. Aristotle, one of the most revered ancient philosophers, was no exception. Despite his many contributions, his works contained numerous inaccuracies that became increasingly evident as science advanced.

For instance, Aristotle claimed that dogs’ skulls were made from a single bone, that bees collected honey that fell from the sky, and that horses had bones in their hearts. These errors highlighted the limitations of relying solely on ancient texts without verification. Pliny the Elder, another ancient authority, also penned some dubious claims in his Natural History, blending fact and myth in a way that fascinated later scholars but also misled them.

Buffon’s Hypothesis: Degeneration of New World Species

As empirical science gained ground, new encyclopedic works began to emerge. One of the most influential was Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon’s Histoire Naturelle. Buffon’s 36-volume series attempted to catalog the natural world comprehensively, but it also introduced controversial theories, especially about the animals of the New World.

Buffon argued that species in America had “degenerated” compared to their Old World counterparts, a view that extended to humans. He claimed that due to poor nutrition, damp climates, and swamps, American natives were lazy, lacked physical vigor, and even had smaller reproductive organs. This “degeneracy hypothesis” angered Americans, who felt it insulted their land and people. Buffon’s theory wasn’t just an academic curiosity; it carried implications for trade, immigration, and national pride.

Thomas Jefferson’s Campaign Against Degeneracy

Thomas Jefferson, then serving as the American minister to France, took Buffon’s remarks personally. Determined to disprove the notion of American inferiority, Jefferson devoted a large section of his only book, Notes on the State of Virginia, to debunking Buffon’s claims. He even went to great lengths to present Buffon with physical evidence, including the skin of a panther and a stuffed moose, hoping these impressive specimens would change the Comte’s mind.

However, Buffon remained unmoved by Jefferson’s efforts, even after receiving a moose that had undergone a challenging journey involving missing antlers, frozen forests, and a creative addition of elk horns. Jefferson’s attempts to defend the dignity of the New World highlighted the broader cultural clash between European skepticism and American determination.

The Great American Incognitum: A Giant Misunderstood

Amid the debate, American naturalists uncovered something extraordinary in the early 1700s at Big Bone Lick, Kentucky: enormous fossilized bones. These bones, later assembled in Philadelphia, revealed a creature unlike anything known—a gigantic, elephant-like beast dubbed the “Great American Incognitum.” Naturalists, eager to emphasize the ferocity and size of this animal, mistakenly added claws from a giant ground sloth and exaggerated its proportions, believing it to be a carnivorous terror of prehistoric America.

Charles Willson Peale and his son Rembrandt displayed the first complete skeleton of the Incognitum, capturing public imagination with dramatic descriptions of the beast as a monstrous carnivore that could destroy forests and devour entire villages. The skeleton toured America and Europe, captivating audiences with the idea that such fearsome creatures had once roamed the continent.

Mastodon and the Birth of Extinction Theory

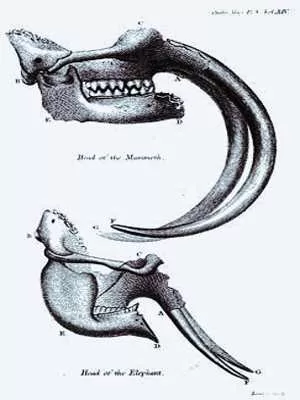

The fascination with the Incognitum led to further scientific investigation, notably by Georges Cuvier, a pioneering anatomist and naturalist. In 1796, Cuvier examined the bones of the Incognitum and named it the “mastodon,” based on the nipple-like shapes of its teeth. This discovery was groundbreaking because it challenged the prevailing belief that all species created by God still existed in some form.

Cuvier’s work on the mastodon was one of the first to argue convincingly for the reality of extinction, a concept that upended traditional views of a perfect, unchanging natural world. His findings forced scientists and theologians alike to reconsider the idea of a divinely ordered Great Chain of Being. If species could go extinct, then the natural world was not static; it was dynamic, filled with change and loss.

The Legacy of the Incognitum and the Rise of Evolutionary Thought

Cuvier’s identification of the mastodon as a herbivore rather than a monstrous carnivore didn’t just correct misconceptions; it laid the groundwork for future evolutionary theory. The idea that creatures could disappear, adapt, or evolve reshaped our understanding of life on Earth, influencing thinkers like Darwin and paving the way for modern biology.

The journey from a tin box with a decorative elephant to the halls of scientific discovery is a reminder of how human curiosity can transform our understanding of the world. From Aristotle’s ancient errors to the debates between Buffon, Jefferson, and Cuvier, each discovery—no matter how flawed—has contributed to the ever-evolving narrative of natural history. As we continue to question, observe, and explore, we honor the legacy of those who dared to challenge the wisdom of the past in the pursuit of truth.