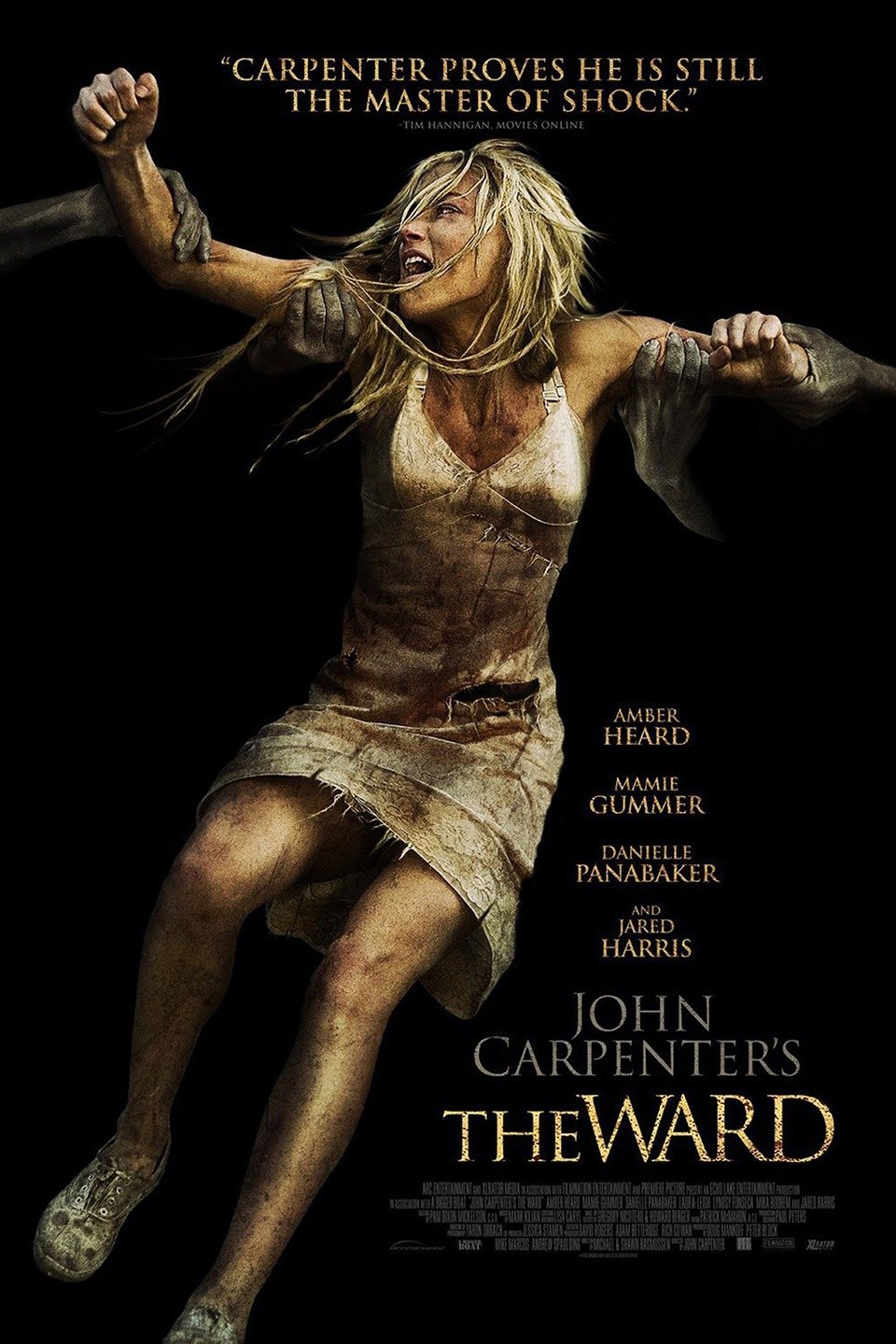

The Ward (2011) Movie

John Carpenter’s return to the big screen after a decade’s absence is cause for both excitement and anxiety from fans. Carpenter’s messy output in the 1990s deserves some reappraisal, especially his Vampires (1998), a glorious camp satire on action machismo and a film fascinatingly preoccupied with corporeal destruction of nominally inhuman monsters, and the beautifully coherent structuring of the schlock epic Ghosts of Mars (2001).

But it’s hard to deny Carpenter, who had made a name for himself through his uncanny sense of rhythm and storytelling precision, was barely bothered in making many of his films fit together as he had been; movies like Escape from LA (1997) and In the Mouth of Madness (1995) were crazy train wrecks of movies with more ideas then sense.

The Ward, which sees Carpenter following in the footsteps of James Mangold’s Identity (2003) and Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island (2010) in playing out gimmick psycho-thriller material, very quickly proves different: here Carpenter is playing the cinematic equivalent of a five-finger exercise, applying his expert, compact cinematic energy to a screenplay written by others (Michael and Shawn Rasmussen) and riffing on familiar refrains. As such, it’s a very minor but still quietly delightful success, as Carpenter bolts concise visuals and a steadily cranking pace to a story that has no pretensions to deep seriousness, and comes up all the better for it. Ironically, the cheery absurdity of the material spurs Carpenter to indulge his showman’s streak.

The year, as a title informs us, is 1966: Amber Heard is Kristen, a lank-haired young woman glimpsed darting through the woods in a slip, eluding a patrolling police car, before coming across a remote farmhouse which she sets fire to. The police drag her away from the scene as she struggles furiously, and she’s placed into a locked ward in a big dark old hospital. There, she meets her fellow inmates: bespectacled, arty Iris (Kick Ass’s Lyndsy Fonseca), bitchy seductress Sarah (Danielle Panabaker), obtuse redneck Emily (Mamie Gummer), and regressive, child-like Zoey (Laura-Leigh).

They’re all under the care of psychiatrist Dr Stringer (Jared Harris), and the watchful eye of humourless Nurse Lundt (Susanna Burney) and sinister orderly Roy (Dan Anderson). The set-up and mix of patients on the ward seems strange; even stranger is the fact Kristen keeps glimpsing a stranger darting by the door of her cell, finds the broken remnants of a bracelet under her bed, and slowly comprehends the uneasiness of her fellow patients, who believe no-one ever gets released from the ward. Kristen is beset by bad dreams of being chained up in a basement as a child, with a hulking man approaching her, clearly about to molest her. When Iris is taken in for a session with Dr Stringer, he hypnotises her, and when she awakens she’s being bundled along by a grotesque wraith, which kills her by jamming a syringe in her eye.

The Ward should be regarded as an attempt to reinvigorate the “fun” horror film of the past, and it succeeds in a fashion that’s far more integral and intelligible than Sam Raimi’s attempt to do the same thing with Drag Me To Hell (2009). What Carpenter’s return should not be burdened with is the expectation that in returning he stands a chance of reviving the relevance of old-school horror cinema after Wes Craven’s relative failure with Scream 4 (2011).

Whilst moving with a quicker, less deliberate pace of editing than was displayed in his classics, the early sequences of The Ward are still laid out with a classic Carpenter sense of mood, his camera exploring the shadowy aisles of the hospital’s interior scanning the hospital’s menacing exterior, roving widescreen shots that absorb multiple levels of detail and frames that bind actions together. His usual talent for mustering an ensemble cast is also soon apparent, in the toey interaction of its young actresses. Carpenter doesn’t push the film’s period setting hard, using it mostly as an excuse to indulge some of the old-fashioned paraphernalia of psych-ward horror (unfortunately, no-one says “Nymphos!”, but there is a nude shower scene), as when Kristen, after a hysteria attack, is subjected to electroshock therapy.

The period settings, and the events underpinning The Ward, have a certain consequential depth, as Carpenter, who made female characters essential not just as pursued victims but as psychic focal points and springboards for horror with Halloween (1978), here presents characters who seem ever so slightly overstated in their schismatic, role-playing qualities, who might form one functioning person if combined. Nascent warrior-woman Kristen emerges from a past of trauma and forms a hard new point-guard to the group neurosis, and represents, after a fashion, the modern woman being painfully born. There’s a casually great scene early on, where the girls dance to bubblegum pop on the ward, only to be plunged into blackness by a power failure, with menacing visions of the spectral assassin haunting them glimpsed in stroboscopic lightning blasts.

That assassin, when glimpsed, is an amusingly retrograde manifestation of beyond-the-grave grotesquery. The question as to where the threat is coming from, and why the ward authorities seem to be covering it up and even facilitating it, becomes the most urgent engine of the plot, as, of course, none of the staff believes Kristen’s attempts to alert them to the menace assaulting the girls.

After Iris vanishes, Kristen believes she has to escape, and she and Emily break out of the war, crawling through air ducts and eluding staff, until they finish up in the hospital morgue. But rather than finding Iris, as she hoped, Kristen finds only the wraith, waiting for her. I supposeThe Ward will be, and should be, castigated for its cheerful clichés and already over-familiar twist ending, in an era where novelty is everything and self-seriousness is a rule, but frankly I wasn’t watching it for that.

I was watching it for the fun of seeing Carpenter orchestrate his increasingly intense stalk and chase sequences, eliciting impressive suspense without much gore or post-production gimmickry. He stokes a great lead performance from Heard, who, having played a not-dissimilar role as a Janus-faced beauty in Jonathan Levine’s All the Boys Love Mandy Lane (2006), possesses the kind of premature gravitas and husky-voiced self-assuredness that easily evokes some of the actresses Carpenter once favoured. In real life and on screen, Heard suggests the regulation blonde hottie but with a subtle dissonance in experience and outlook, and it’s a quality that invests Kristen, whose survivalist grit proves to have a very interesting genesis.

In short The Ward might well be a more effective, as well as much less pretentious, take on the theme than some of its recent antecedents, in which the drama one sees in the bulk of the movie proves to be an interior psychic battle. But there’s a fleetingness to Carpenter presenting a heroine who is Laurie Strode and Michael Myers and all the others too, contained in the one skin. Likewise Carpenter’s institutional paranoia is apparent throughout, especially in the images of the opening credits in which practices of witch-hunting and medieval torture are suggestively correlated with ‘60s psychiatric techniques.

Whilst the film doesn’t possess that innately individual, eccentric yet hypnotic rhythm that can make even Carpenter’s less successful films worth repeated viewing, a la Prince of Darkness (1987), nor much of his trademark dry humor, nonetheless the expert tension-building and no-bullshit editing in sequences when Kristen and Emily, and later Zoey, try to escape the ward, are master-classes in this sort of thing.

The final scenes, with hopes of regeneration springing from enthralling trauma, nonetheless give way to the customary Carpenter refusal to give complete closure, with an eruptive personality that just won’t be repressed, not after having been schooled in the necessities of survival, exploding from a mirror (evoking, at once, the similar, if more subtle, final shot of Prince of Darkness as well as the vicious black punch-line of The Fog, 1979) to reclaim her progenitor. And perhaps, given the film’s portrayal of therapy attempting to nullify experience and survivalist capacity in favour of the illusion of normality and conformity, that’s not such a depressing coda.