n

n

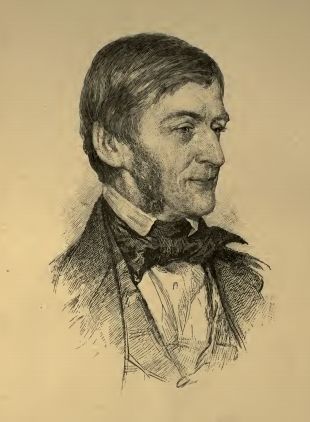

n She had with her letters of introduction, written fornher by Ralph Waldo Emerson (amongst others), and in June 1853 she called on thenfamous writer, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle at his home in CheynenRow, Chelsea. Carlyle and his wife received Bacon with affection and kindnessnalthough there are hints that they were also patronisingly indulging theirnvisitor and her queer notions for their own amusement.

n

n

n

n

|

n

| Ralph Waldo Emerson |

n

n

n

n

nEmerson had written tonCarlyle that Miss Bacon,

n

n

n

n“… has a private history that entitles her to highnrespect,”

n

n

n

nand Carlyle replied,

n

n

n

n“As for Miss Bacon, we find her, with hernmodest shy dignity, with her solid character and strange enterprise, a realnacquisition,” adding, “I have not in my life seen anything so tragicallynquixotic as her Shakspeare enterprise: alas, alas, there can be nothingnbut sorrow, toil, and utter disappointment in it for her.”

n

n

n

nHowever, therenis a different tone in a letter Carlyle wrote to his brother,

n

n

n

n“For thenpresent, we have (occasionally) a Yankee Lady, sent by Emerson, who hasndiscovered that the ‘Man Shakespear’ is a Myth, and did not write those Playsnwhich bear his name, which were on the contrary written by a ‘SecretnAssociation’ (names unknown): she has actually come to England for the purposenof examining that, and if possible, proving it, from the British Museum andnother sources of evidence. Ach Gott!—.”

n

n

n

nBacon herself, in a letter to hernsister, provides more light on their meeting,

n

n

n

n“Do you mean to say,’ so andnso, said Mr. Carlyle, with his strong emphasis; and I said that I did; and theynboth looked at me with staring eyes, speechless for want of words in which tonconvey their sense of my audacity. At length Mr. Carlyle came down on me withnsuch a volley. I did not mind it the least. I told him he did not know what wasnin the Plays if he said that, and no one could know who believed that thatnbooby wrote them. It was then that he began to shriek. You could have heard himna mile.”

n

n

n

nIf nothing else, it’s nice to imagine that dour Scot Carlyle beingnreduced to shrieking.

n

n

n

n

|

n

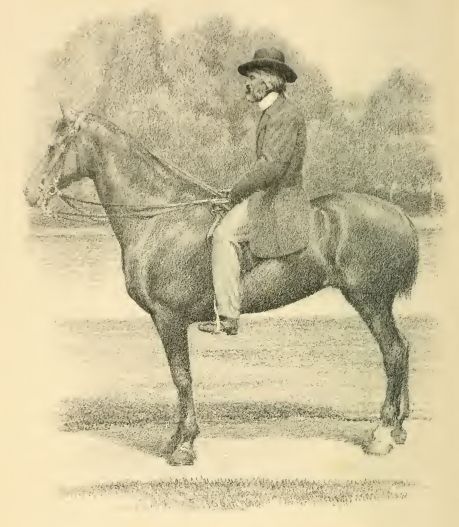

| Thomas Carlyle sitting on a horse. |

n

n

n

n

nAfter a stay in London, Bacon moved to St Albans – afternall, Sir Francis had been Viscount St Albans. The money allotted to her by hernAmerican patrons had been intended to last for the summer of 1853 but Delia,nused to poverty, managed to spin it out long enough to last for two years, asnshe toiled away on her book, and when she couldn’t afford to light a fire, shenwrote propped up in her bed in order to keep warm. In November 1854, the coldndrove her from St Albans back to London,

n

n

n

n‘… it was uniformly colder in mynroom than it was out of doors in the daytime.’

n

n

n

nThe Carlyles found hernlodgings and provided her with meals, and Carlyle advised her on Englishnpublishers, offering, if needed, to write an introduction for her book, whereasnEmerson offered to deal with the American part of the enterprise. However,nthere were problems, as Bacon was dealing with one publisher through Emersonnand dealing with another directly herself.

n

n

n

n

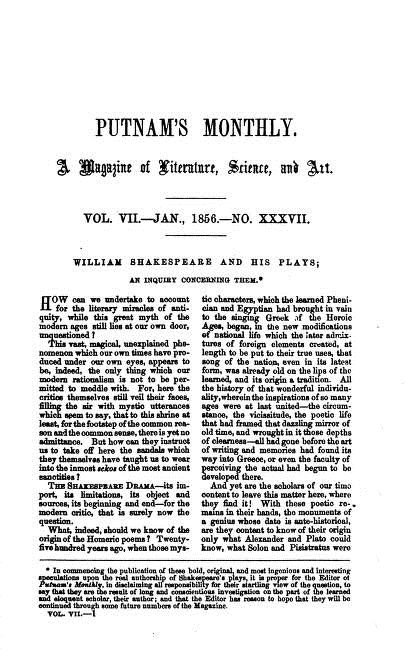

|

n

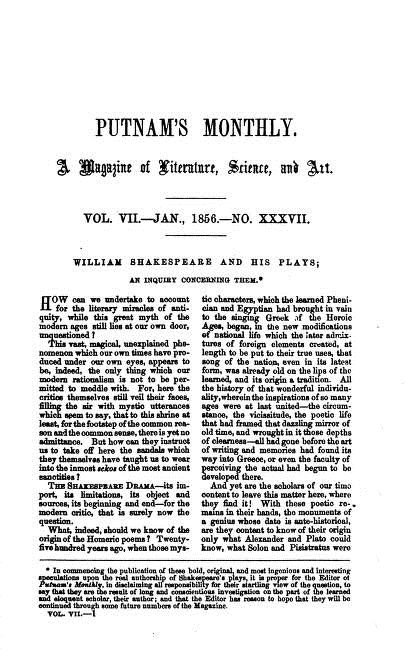

| Delia Bacon – William Shakespeare and his Plays – Puttnam’s Monthly – January 1856 |

n

n

n

n

nThis confusion resulted in annarticle appearing in Puttnam’s Monthly as ‘William Shakespeare andnhis Plays: An Inquiry Concerning Them’ in January 1856, for which shenreceived a much-needed eighteen pounds fee, but it caused the Americannpublisher that Emerson had negotiated with to publish her work as a book tonwithdraw that offer. To issue her book as a series of magazine articles insteadnwas not really what anyone had intended, and it was Bacon’s lack of businessnsense that almost scuppered everything. The position wasn’t helped when Londonnpublishers began to write polite letters of rejection to Bacon, all of themnseemingly unwilling to publish any criticism of the National Bard.

n

n

n

n

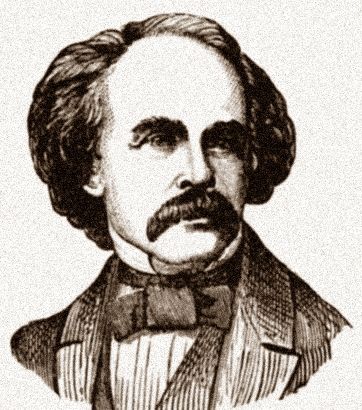

|

n

| Nathaniel Hawthorne |

n

n

n

n

n

Help camenthrough Nathaniel Hawthorne, the extremely famous and respected Americannauthor, who was also the Consul to Liverpool, a lucrative but unappealingnposting. Bacon wrote a modest letter to Hawthorne (she was a close friend ofnMiss Elizabeth Peabody, the sister of Mrs Hawthorne), asking for counsel andnassistance and Hawthorne’s sense of honour meant that he could not refuse hernappeal, regardless of the cost in time and effort to himself. His help came atnprecisely the right time for Bacon, as Emerson began to express doubts of evernfinding an American publisher who would be willing to undertake the productionnof her book, and who then added to her troubles by informing her that the copynof her manuscript in America had been mislaid. n

n

n

|

n

| Nathaniel Hawthorne – Our Old Home – 1863 (1891 ed). |

n

n

nIn his collections taken fromnhis English notebooks and published as Our Old Home, Nathaniel Hawthornendescribes the single meeting he had with Bacon, in London in late July 1856.nThe chapter is called Recollections of a Gifted Woman, and in itnHawthorne describes a tall, elegant middle-aged woman, striking now and ‘exceedinglynattractive once’, who speaks friendlily and openly about her theories.nAlmost at once, Hawthorne realises that she has become a ‘monomaniac’, and thatnher belief in her ideas,

n

n

n

n“… had completely thrown her off her balance.”

n

n

n

nShe placed a hand on a book of Francis Bacon’s letters and confides how she hasndiscovered within them a key, secret but definite and precise instructions onnhow to find a will and other documents that were concealed in a hollow space innthe under-surface of Shakespeare’s gravestone, which would provide undeniablenproof of her theories. In a low, quiet tone, she went on to explain hownProvidence was guiding and providing for her; she had been led to her currentnlodgings and her kindly landlord and landlady. Hawthorne himself had beennprovided for her, a sympathetic, American author with the power experience andninfluence to aid her, just at the precise time when she needed a negotiatornwith the publishers. He bit his tongue, hoping that there remained in her NewnEngland head enough common sense to spare her from her from the worst of herncurrent bewilderment.

n

n

n

n

|

n

| Miss Delia Salter Bacon |

n

n

n

n

nHawthorne left Bacon after about an hour and they nevernmet again, but a story reached him that some months previous to his interviewnDelia Bacon had gone to Stratford, taken lodgings and started to haunt thenchurch in which Shakespeare was interred. She became acquainted with the clerknand began to sound him out regarding access to the tomb. Sensibly, the clerkninformed the vicar who, on learning the facts, sought the advice of a lawyer.nShe was told that it might well be possible for her to have the gravestonenlifted, if it were done in the presence of the vicar and his clerk, and afternnightfall. Then, the doubts began. Had she really read her Bacon correctly? Henmentioned a tomb, but was it Shakespeare’s tomb, or his own, or Sir WalternRaleigh’s, or that of Edmund Spenser. She held back but continued to haunt thenchurch. One night, she crept in alone with a dark lantern in her hand andngroped her way towards the chancel. She sat by the grave, examined the gaps innthe stones but did nothing else. Presently, the clerk emerged from the darknessnand made his presence know; he had been watching her all along. The tombnremained unopened.

n

n

n

nTomorrow – from bad to worse

n

n

n

n