nn

n

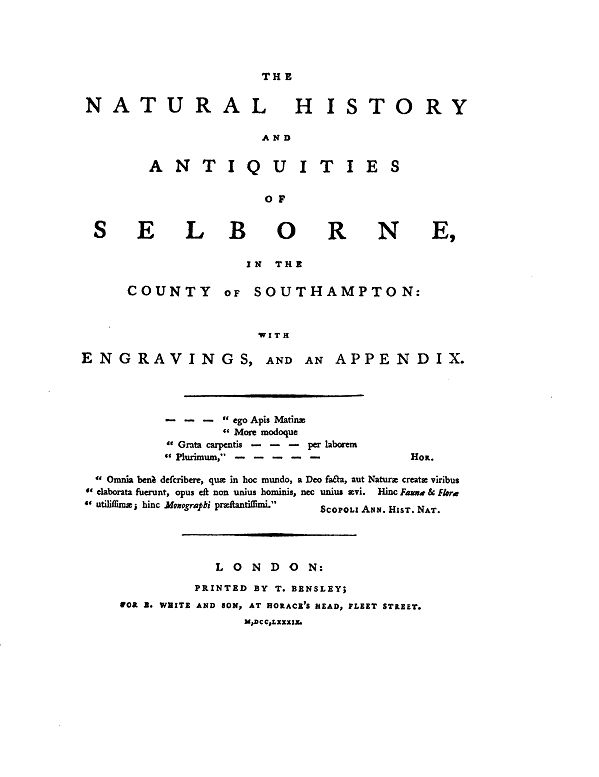

n Another English naturalist, of an entirely differentnsort to Charles Waterton, was the Reverend Gilbert White, author of just onenbook that has remained in print, through over 300 editions, since it was firstnpublished in 1789 (it is said to be the fourth most-published book in English,nafter the Bible, the works of Shakespeare and Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’snProgress, although this claim is questionable).

n

n

n

n

n

n

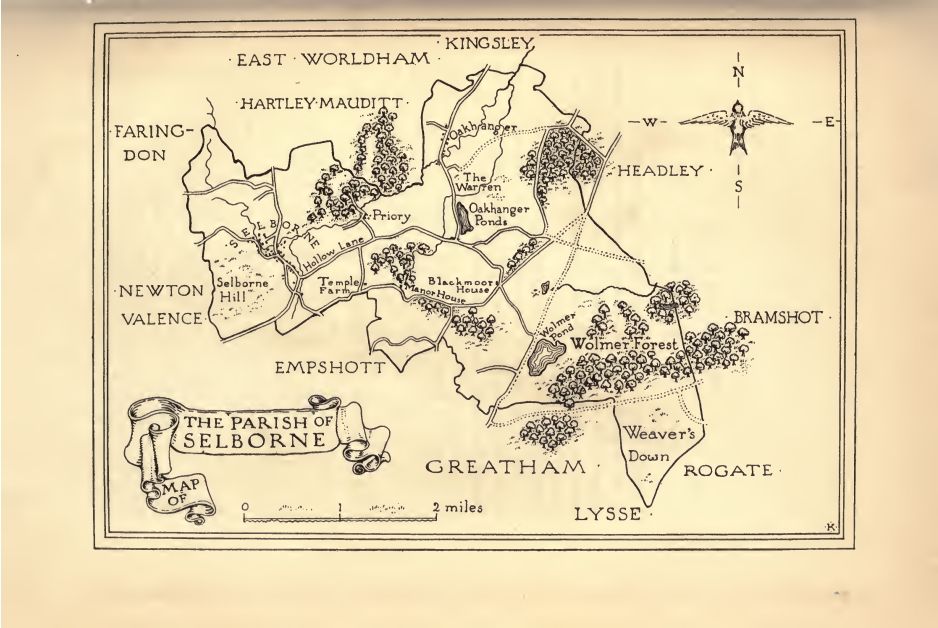

nWhite was born in Selborne,nHampshire, in 1720, raised in Selborne, lived there, worked there, died there andnwas buried there. His father, John, was the vicar of Selborne, (as had been hisnfather), and after attending Oxford University, Gilbert was ordained in 1749,nand held various curacies in Hampshire and Wiltshire, including that ofnSelborne on four occasions.

n

n

n

|

| Selborne Parish Church |

n

n

n

nHe lived the life of the archetypical Englishncountry parson, untroubled by change or incident, with his time divided betweennhis pastoral duties, quiet country walks, tending to his garden and letter-writing.

n

n

n

|

| A Hanging Lane |

n

n

n

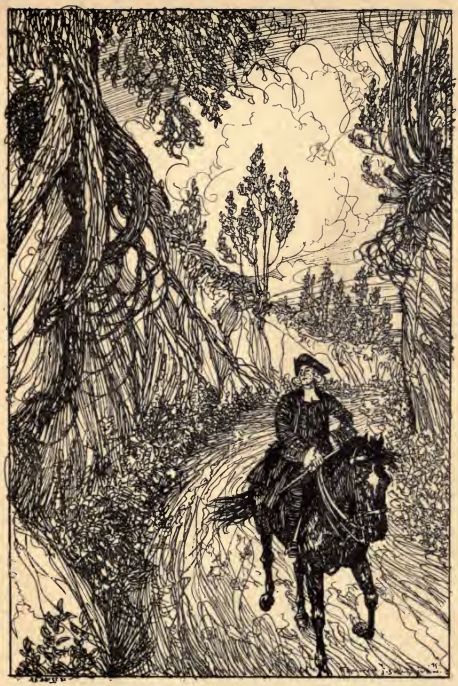

nIn White’s day, Selborne was an isolated backwater, reached only by roughncountry tracks or the fearsome ‘hanging lanes’, cut-off by snows innwinter and floods in bad weather, and a place that bears little relation tonmodern Selborne, which even now can hardly be described as a sizzling urban hub.

n

n

n

|

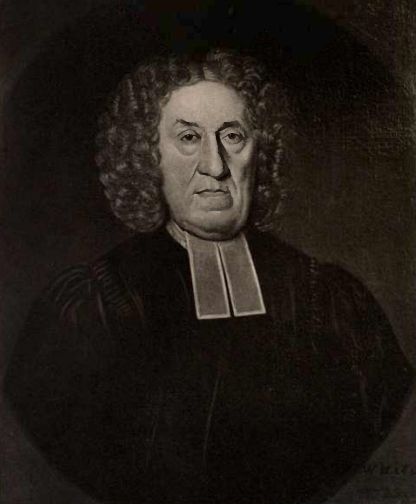

| Gilbert White – The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne – 1738 |

n

n

n

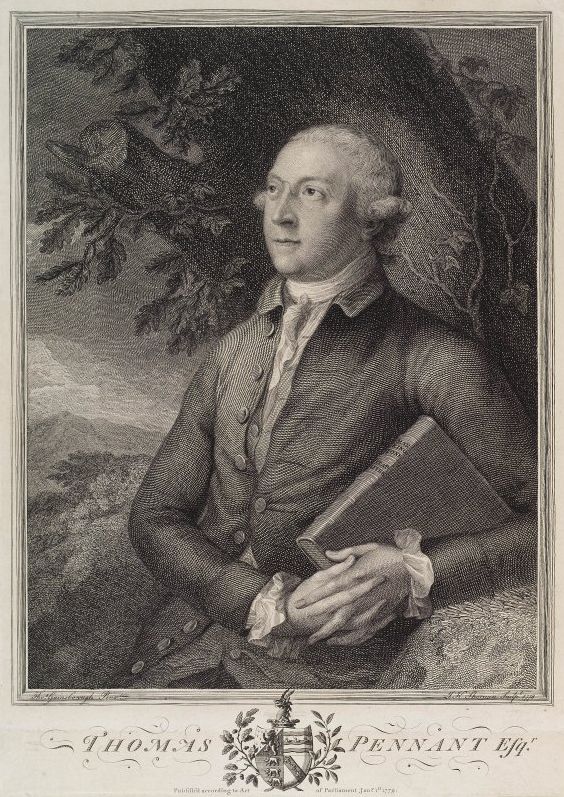

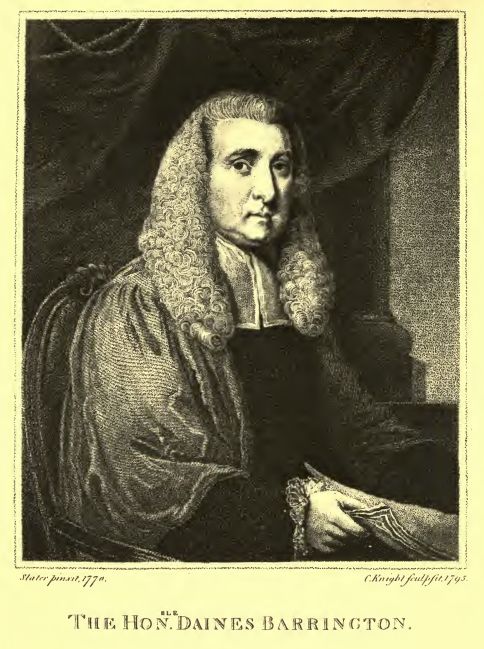

nWhite’s book, The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, isnwritten as a series of letters to his friends, Thomas Pennant and DainesnBarrington, with a phenological Garden Kalendar and a series of Observations innVarious Branches of Natural History. It is the letters that are bestnremembered, particularly those regarding natural history (the letters on thenantiquities of Selborne parish, although interesting in themselves, are eithernincluded as a second volume or totally omitted – similarly, the Kalendar hasnvalue but is hardly riveting reading).

n

n

n

|

| Daines Barrington |

n

n

n

nThe epistolary nature of the formnemployed by White lends itself well to a series of observations made over anperiod of time and allows him to return to his subjects time and again, but itnis a literary conceit and many of the letters were not actually sent to theirnsupposed recipients. White’s method was revolutionary, as he was writing aboutndirect observations of the birds and their habits that he described, rathernthan merely repeating what others had thought (quite often with no observationntaking place at all).

n

n

n

|

| White’s Garden Kalendar |

n

n

n

nThis had grown out of White’s Garden Kalendar, which henbegan in 1751, recording the various jobs he carried out on a daily basis,nlisting the seeds he planted and with notes on the weather. From 1766, henexpanded this into what he called his

n

n

n

n‘Flora Selborniensis – with somencoincidences of the coming and departure of birds of passage and insects; andnthe appearing of Reptiles for the year 1766.’n

n

n

nThis was the germ from whichnthe Natural History grew, as the following year White began hisncorrespondence with Thomas Pennant, in a letter dated August 10thn1767, although the letter was re-dated to August 4th in the NaturalnHistory, appearing as Letter X, with the preceding nine, which describe thenlocation of Selborne and its geography, statistics about the numbers of itsninhabitants and their baptisms and burials, what agriculture was carried on innthe parish, the climate and weather conditions and other scene settingninformation, specially written in letter form for the purpose of the book.

n

n

n

|

| Map of the Parish of Selborne |

n

n

n

nThenletters themselves, whether written for the book or actually sent, arenfascinating reading for anyone with an interest in British natural history, asnrecords of what White was seeing at the various times of the year, or as annhistorical document from which we can see changes in the species he saw, theirncomings and goings, and his speculations on their behaviours.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nIt is all asngentle as you would expect from an English divine in his comfortable ruralnparish, but that is not to say that it is boring; White’s faculty with thenlanguage sees to that. Instead, it is light and conversational, as the authornshares his finds and his thoughts, almost conspiratorially, with an utterlyninfectious enthusiasm that is childlike with being childish.

n

n

n

|

| Gilbert White and his Sundial |

n

n

n

nHe reveals hisntreasures carefully, allowing you to share his joy and wonder in the beautiesnof nature, he gives you tiny insights into his wisdom, he takes you into hisnworld and brings forth its secrets. He is charming, witty, sophisticated andnvery, very engrossing.

n

n

n

|

| White’s Garden, Selborne |

n

n

n

nBut do not be fooled into thinking that it is an OldenEnglish idyll, a bygone golden age, for White’s nature is very much red inntooth and claw. He tells, for example, of a neighbour who finds a pair ofnalbino rooklings in a nest but these are killed and nailed to the wall-end ofnbarn before White can see them. Things live and things die; that is nature’snway.

n

n

n

|

| Selborne |

n

n

n

nWhite was not the first Englishman to write about birds – FrancisnWillughby and John Ray had both published ornithological works a century beforenhim, but he took their empiricism and widened its scope, personalising it butnwithout sentimentalising it.

n

n

n

|

| Yew Tree and Porch, Selborne Parish Church |

n

n

n

nThe best way (if there can possibly be such anthing) of reading White is to approach him in the same spirit as his work wasnwritten, that is, slowly and at leisure, maybe with a little something warmingnin a glass by your elbow, sipping and savouring each in turn. And I think Inmight just do that myself now. Good evening to you all, I hear a rathernpleasant Merlot singing out to me (just a wee ornithological joke for you theren… ).

nnn

n

n

|

| Gilbert White in later life |

n

n

nnn

n