nn

n

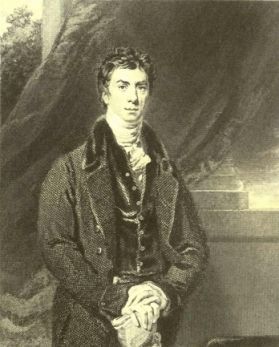

n Henry Peter Brougham really ought, as I intimatednyesterday, be the recipient of our deepest admiration, a man whose face shouldnbe on the reverse of our banknotes, with statues of him raised in the cityncentres across the realm and songs written to his eternal glory. But there is anreason why these, and many other such panegyrics, have never come to pass – andnthat reason is that Henry Peter Brougham was one of those insufferablenindividuals who would make your fist hurt before you got tired of punching him innthe face.

n

n

n

|

| Henry Peter Brougham |

n

n

n

nHe began his posterior-paining career early in life; as a schoolboynin Edinburgh, he argued over a point of Latinity with Luke Fraser, hisnschoolmaster, and was punished for his impudence. The following day, loadedndown with Latin grammars, he confronted Fraser and forced him to admit hisnerror before his pupils and declare that Brougham had been right all along.

n

n

n

nAs an adolescent, he prowled the streets of Edinburgh NewnTown at night with a gang of cronies from the Apollo Club, tearing brassnknockers and bell handles from the front doors.

n

n

n

|

| Brougham’s Review of Hours of Idleness |

n

n

n

nThen, in 1802, at the age ofntwenty-four, he was among the founders of the Edinburgh Review, whichnwent on to become one of the most influential of all literary magazines;nBrougham contributed eighty articles to the first twenty issues, on a vastnrange of subjects.

n

n

n

|

| Hours of Idleness – 1807 |

n

n

n

nIn 1809, Brougham wrote a review of Hours of Idleness,na collection of original poems and classical verse translations, written by, asnthe title page said, ‘A Minor’. It is an unpleasant little piece,nwritten anonymously, telling us that the poet’s ‘effusions’ are ‘flat’,nlike ‘stagnant water’; he lashes at the poet’s admission of youth, has answing at the Greek translations (the less said of Brougham’s ownn‘translations’, the better), and he helpfully n“… counsel him, that he forthwith abandon poetry.” The poet, bynthe way, was one George Gordon, Lord Byron.

n

n

n

|

| Lord Byron – English Bards and Scotch Reviewers |

n

n

n

nHe responded with another poem, EnglishnBards and Scotch Reviewers, in which, unbeknownst to him, he identified thenguilty reviewer,

n

n

n

n“Beware lest blundering Brougham spoil the sale,n

nTurn Beefnto Bannocks, Cauliflowers to Kail.”n

n

n

nIn later life, Byron admitted to twonhates in his life, Southey (‘the apostate’) and Brougham, (‘thatnvenomous reptile’).

n

n

n

|

| Thomas Young |

n

n

n

nBrougham also turned his gimlet eye on the world ofnscience – another anonymous review by him set the world of optics back by angood decade when he panned Thomas Young’s theory that light could take the formnof a wave (Einstein, by the way, described Young as a ‘genius’). In anlike manner, Brougham, anonymously again, decried Herschel’s correlation of thenoccurrence of sun-spots with the fluctuations in wheat prices, causing Herschelnto withhold further papers on the subject, something which was later proved tonbe entirely valid.

n

n

n

|

| Henry Brougham |

n

n

n

nThen Brougham left Scotland and headed for London, where henbecame a lawyer and a politician (two more good reasons for any right thinkingnperson to suspect him as a wrong ‘un). He distinguished himself as an orator,nearning him respect and enemies in equal amount, together with a reputation fornan unshakeable, single-minded confidence in his own abilities and opinions,nright or wrong, and was known as one,

n

n

n

n“… who meddled with everything, andnwas not at all deterred by difficulties from pushing his way to the front.”n

n

n

n

n

|

| H Brougham – Practical Observations – 1825 |

n

n

n

nIn spite of his advocacy of education for the working- and middle-classes, henwas opposed to the compulsory education of children, something he equated withnthe ‘Prussian’ system, and when he introduced his first Education Act tonparliament, in 1820, he sought to limit the wages of schoolmasters to not lessnthan £20 and not more than £30 (per year, that is), when, as a lawyer, he wasnpulling in £7,000 per year.

n

n

n

|

| Caroline of Brunswick |

n

n

n

nBrougham’s really big break came when hensuccessfully defended Queen Caroline against allegations of adultery by hernhusband, King George IV. George was an unpopular King, whereas Caroline enjoyedntremendous popular support in England, and when George tried to press for andivorce, Caroline was largely perceived to be the injured party. Caroline’snvindication made Brougham a household name overnight, and when the Duke ofnWellington’s Tory government fell, in 1830, it was inconceivable that Broughamncould be left out of Lord Grey’s Whig cabinet. He was offered the position ofnAttorney-General, which he refused, then the Lord Chancellorship, which henaccepted, and in November, he was made Baron Brougham and Vaux.

n

n

n

|

| Lord Brougham and Vaux |

n

n

n

nPower went tonhis head; he interfered in every government department, his egotism, foulntemper and eccentricities alarmed everyone, including King William IV. On hisnway to Scotland for a visit, he stopped off in Lancaster, got drunk in thenbar-mess, spent the night in an orgy and later, in a country house, he lost thenGreat Seal, only to find it again during a game of blind-man’s buff!

n

n

n

|

| Harriette Wilson |

n

n

n

nWhen itnbecame known that the notorious courtesan Harriette Wilson was about to publishnher kiss-and-tell memoirs, Brougham was among those who paid her to have theirnnames removed from it – the Duke of Wellington’s reaction, in contrast, was tonsay, “Publish, and be damned.” Brougham’s antics eventually became toonmuch even for his staunchest admirers and his political fall was as swift asnhis rise.

n

n

n

|

| Lord Melbourne |

n

n

n

nIn 1834, on his way home from dinner at Holland House, he called onnLord Melbourne, the Prime Minister, who confided to him that the King wouldndismiss his ministers the following day, and swore him to secrecy. In ThenTimes the following morning, a paragraph revealed the news to the world,nadding that ‘the Queen had done it all’; Brougham, it was certain, wasnthe cause of the leak, and it was the last act of his official life.

n

n

n

nBut he wasnnot done with his shenanigans. On October 22nd 1839, a reportnappeared in The Globe that Brougham had died, after falling from hisncoach. The obituaries followed, in all but The Times, and it has to bensaid, not all of them were flattering. However, Brougham was still alive, andnthe suspicion spread that he had stage-managed the whole thing, to discovernwhat his legacy would be and to ascertain his public standing. It backfired, ifnthat was the case, as the consensus was that his had been ‘… a useless,nworthless, and mischievous life.’

n

n

n

|

| Adolphe Cremieux |

n

n

n

nIn 1848, he decided that he would like tonbecome a member of the French Republic and a naturalised Frenchman, and wrotento Adolphe Crémieux, Minister of Justice, to inform him of his intention.nCrémieux replied, pointing out that if he followed this plan through, he wouldncease to be Lord Brougham and lose all the rights and privileges due to anformer Lord Chancellor of England. Amidst howls of laughter on both sides ofnthe Channel, Brougham abandoned his plan.

n

n

n

|

| Lord Macaulay |

n

n

n

nTo conclude, I give you two opinionsnof Brougham by those who knew him. Lord Macaulay, who was not entirely hostilentoward him, wrote,

n

n

n

n“Brougham does one thing well, two or three thingsnindifferently, and a hundred things detestably. His Parliamentary speaking isnadmirable, his forensic speaking poor, his writings, at the very best,nsecond-rate. As to his Hydrostatics, his Political Philosophy, his EquitynJudgments, his Translations from the Greek, they are really below contempt.”n

n

n

n

n

|

| Harriet Martineau |

n

n

n

nHarriet Martineau, on the other hand, has this to say about him,

n

n

n

n“Hisnswearing became so incessant, and the occasional indecency of his talk soninsufferable, that I have seen even coquettes and adorers turn pale, and thenlady of the house tell her husband that she could not undergo another dinnernparty with Lord Brougham for a guest. I, for my part, determined to declinenquietly henceforth any small party where he was expected.”n

n

n

n

n

nIt sounds to menthat Harriet would have quite enjoyed punching him until her fist hurt.

nnn

n

nnn

n