nn

n

n As ever, John Audubon lacked funds. To raise them hentaught drawing. He taught dancing. He taught French. He taught fencing. Henlearned oil-painting and raffled his works. And when he had raised enough, henset off for Philadelphia, the city of brotherly love and a Mecca for thenscientifically minded.

n

n

n

|

| Example of Audubon’s Portraiture |

n

n

n

nHe arrived in early April 1824, bought himself a newnsuit of ‘extreme neatness’ and presented his credentials to Dr WilliamnMease, a friend from his earlier, more prosperous days. Mease introduced him tonThomas Sully, Robert and Rembrandt Peale, Richard Harlan and Charles LnBonaparte; in turn, Bonaparte introduced Audubon to the Academy of NaturalnSciences.

n

n

n

|

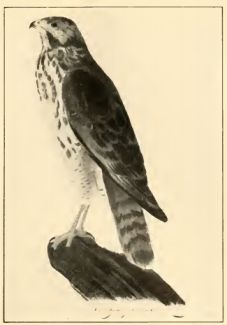

| J J Audubon – Cooper’s Hawk – 1810 |

n

n

n

nHere, Audubon presented his drawings, which were well received andnaroused interest by most but not all. The foremost critic was George Ord, whonbecame Audubon’s most bitter adversary, and whose animosity seems to have beennrooted in jealousy. Ord’s interests were inextricably linked to AlexandernWilson, the Scots ornithologist who had visited Audubon in the counting housenat Louisville and who had written the great nine-volume American Ornithology.

n

n

n

|

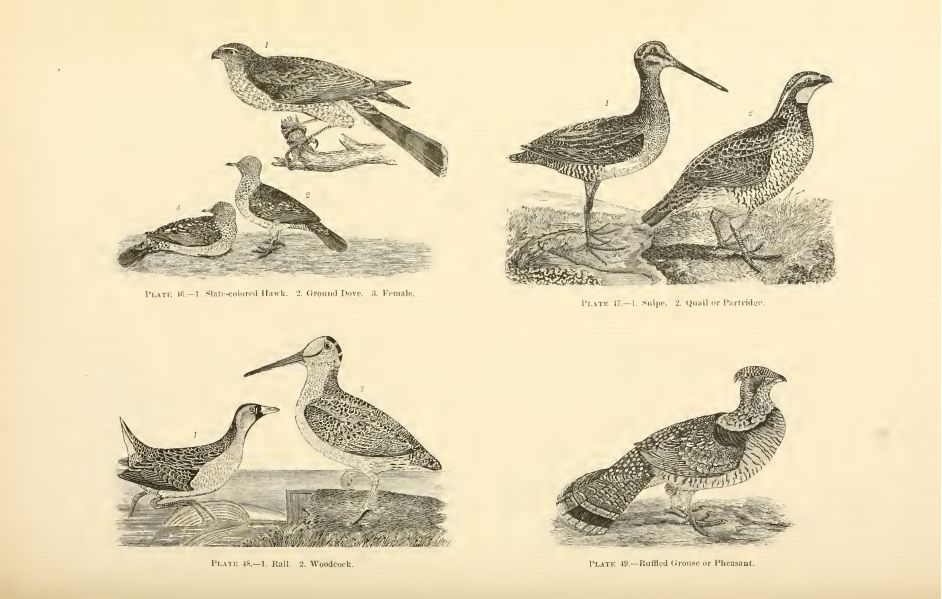

| Illustration from Wilson’s American Ornithology |

n

n

n

nUnfortunately, Wilson had died in 1813, at Philadelphia, and Ord had overseennthe completion of the final volume of the Ornithology, adding a biography ofnWilson written by himself. In 1824, he was responsible for issuing the thirdnedition, in three octavo volumes, containing 76 hand-coloured plates, publishednin New York by Collins and Company, and in Philadelphia by Harrison Hall. MrnHall’s brother, James Hall, was the author of a particularly condemnatorynreview of Audubon’s Birds of America, the same review that heaped praisenon Wilson’s work, (let us remember, Hall’s brother had a substantial financialninterest in the Wilson editions). Ord also objected to Audubon’s use of foliagenand other accessories in his illustrations, an objection that might bensustained in works of a purely technical nature, something that was not whatnAudubon intended.

n

n

n

|

| Charles Lucian Bonaparte (in later life) |

n

n

n

n

n

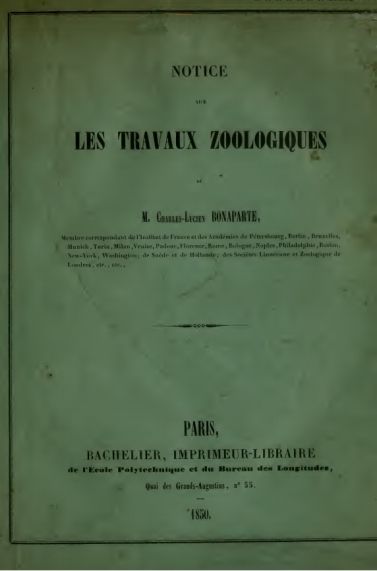

nCharles Lucian Bonaparte was more supportive of Audubon’snwork. He was the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, who had settled in Philadelphianwith his uncle Joseph (the former King of Spain), where he devoted himself tonliterary and scientific pursuits. Bonaparte was well in hand with his own AmericannOrnithology (which was, to be frank, a continuation of Wilson’s work), andnintroduced Audubon to Titian Peale, who was making drawings for him, and ThomasnLawson, his engraver who had also engraved Wilson’s books. Lawson, a Scot, didnnot like Audubon’s drawings, he found them too free and unanatomically correct,nand when Bonaparte said that he would buy them, Lawson said that that was hisnprerogative, but he would not engrave them.

n

n

n

|

| C L Bonaparte – Les Travaux Zoologiques – 1850 |

n

n

n

nOn a more positive note, Audubonnalso met at this time Mr Fairman, another engraver, who urged him to take hisndrawings to Europe and have them engraved there, in a ‘superior style’.nAudubon made a drawing of a Sand Grouse for Fairman, which he engraved for anbanknote for the State of New Jersey. Another acquaintance made at this timenwas Mr Edward Harris, who became a firm friend and supporter. Harris bought allnof Audubon’s works he was offering for sale at the time, and at the artist’snasking prices, and in the future would send him rare and desirable specimens.nAudubon weighed up the valuable advice offered by his new supporters andnresolved to travel to Europe.

n

n

n

|

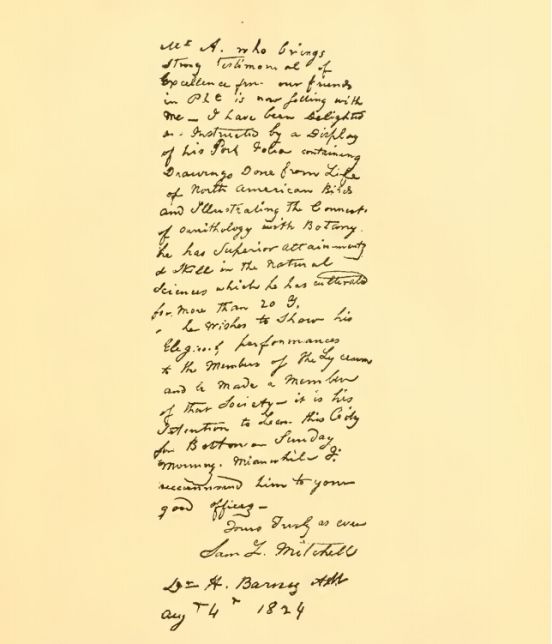

| Letter of Introduction from Dr Samuel Mitchell |

n

n

n

nHe left Philadelphia on August 1stn1824, and went to New York, with letters of introduction which were wellnreceived, and he met Dr Samuel Mitchell, the father of American science, and onnwhose recommendation Audubon was elected to the Lyceum of Natural History, butnsummer found many of the expected contacts away from the city, so Audubonncontinued his progress, going to Albany and then on to the Niagara Falls, allnthe while collecting more drawings for his projected volume covering the entirenbird life of America. Late in 1824, he made his way back to his family, then innLouisiana, whom he had not seen for fourteen months, and he arrived with tornnclothes, unkempt and dishevelled, hair uncut and looking ‘like the WanderingnJew’.

n

n

n

|

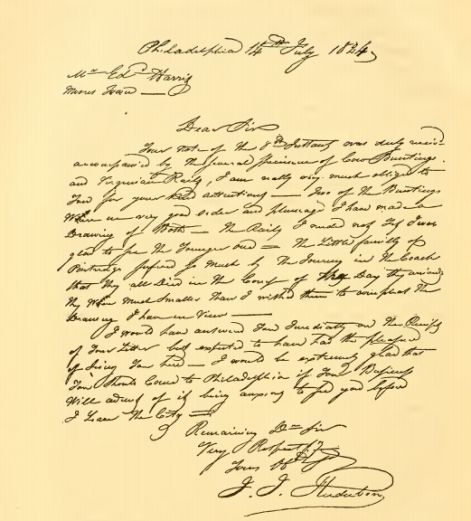

| Letter of Introduction by Edward Harris |

n

n

n

nHis wife’s teaching had brought her good fortune, she was earningnabout $3,000 per year, a very respectable amount in the 1820s, and she was notnonly willing but eager to place her savings at her husband’s convenience. Oncenmore, he fell back on teaching to earn money, opening a dancing school thatndrew in sixty pupils from the surrounding countryside, and he spent his sparenhours improving and revising his collection of ornithological drawings. Hisnnegative experiences in Philadelphia and New York had convinced him that hisnonly option in realising his dream was to travel to Europe, and on May 17thn1826, at the age of forty-one, he boarded the Delos, sailing out of NewnOrleans for Liverpool, under the command of Captain Joseph Hatch.

n

n

n

|

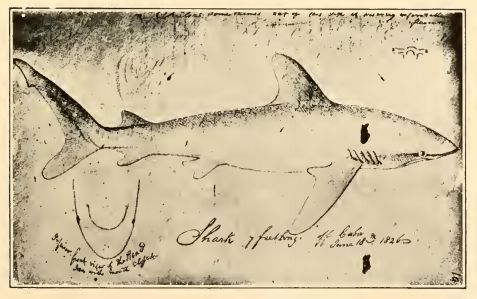

| J J Audubon – Drawing of Shark – 1826 |

n

n

n

nHe did notnwaste his time during the 64 days at sea, he drew sea-birds; gulls, petrels,ngannets, terns and pelicans. He saw sharks and porpoises, and numerous speciesnof strange fishes. The Delos rounded Ireland, into St George’s Channel,npast Wales and Holyhead, and finally made land at Liverpool on Friday July 21stn1826.

nnn

n

nnn

nTomorrow – England

n

n