nn

n

n

n

n Staying with falconry for just a little whilenlonger, you couldn’t be a kid from the north of England in the late sixties andnearly seventies without having seen the film Kes. It was made in 1969nand tells the story of Billy Casper, a fifteen year old Barnsley lad without anprospect or even a hope of a future, who raises and trains a kestrel and, fornthe first time in his life, receives praise from a teacher when he gives annimpromptu talk about the bird in his classroom.

n

n

n

nI’ve never really made my mindnup about Kes – on one hand it seemed to be saying that if you becamenpassionate about a subject it might be possible to rise above a hopelessnsituation and find a way out but another part of me felt that Kes wasnsaying that it was pointless to even try to escape, as your dreams would bentrampled and you’d end up even more disillusioned than before you’d started.

n

n

n

|

| Film poster for Kes |

n

n

n

nLife in northern England, according to Kes, was unrelentingly awful; itnwould batter you into submission as it had done to innumerable generations beforehand.nSchools were factories for the production of either bullies or victims, sondon’t get caught on the wrong side and adult life meant either another factorynof another sort or down the coalmine. The infamous North-South divide ofnEngland condemned those who were unfortunate enough to be born Oop North to anlife of unending grimness and Kes was telling you to accept your fatenand know your place, you northern scum. (Little did we know at the time thatnthings would become a darn sight grimmer in the years to come, but that’s anstory for another day).

n

n

n

|

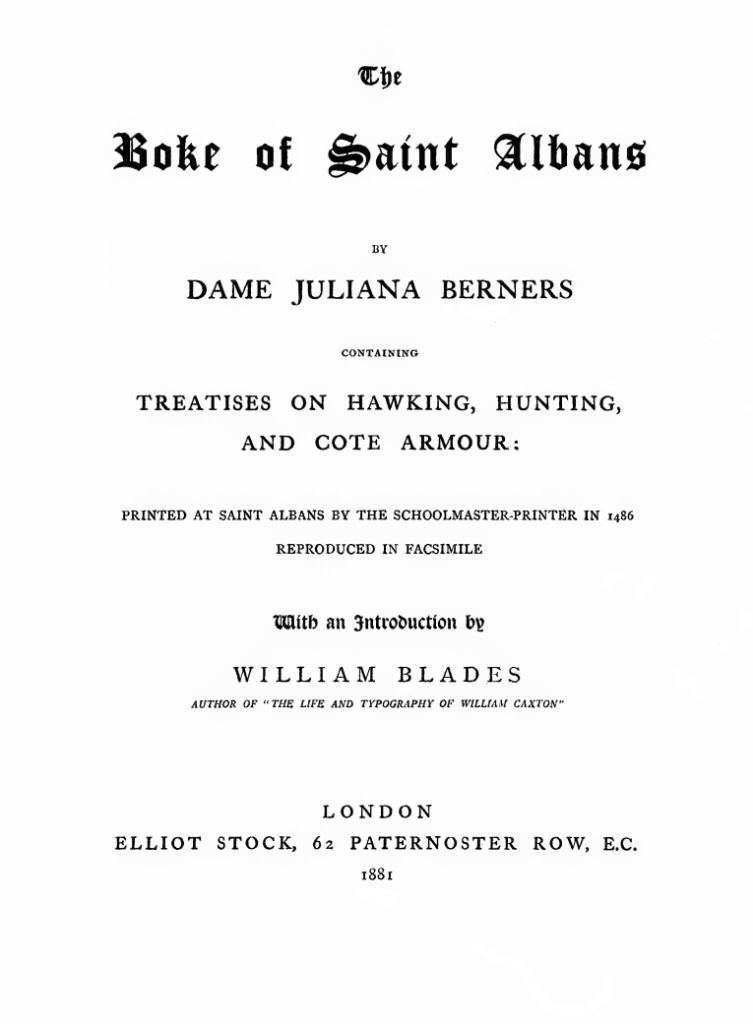

| Barry Hines – A Kestrel for a Knave – 1968 |

n

n

n

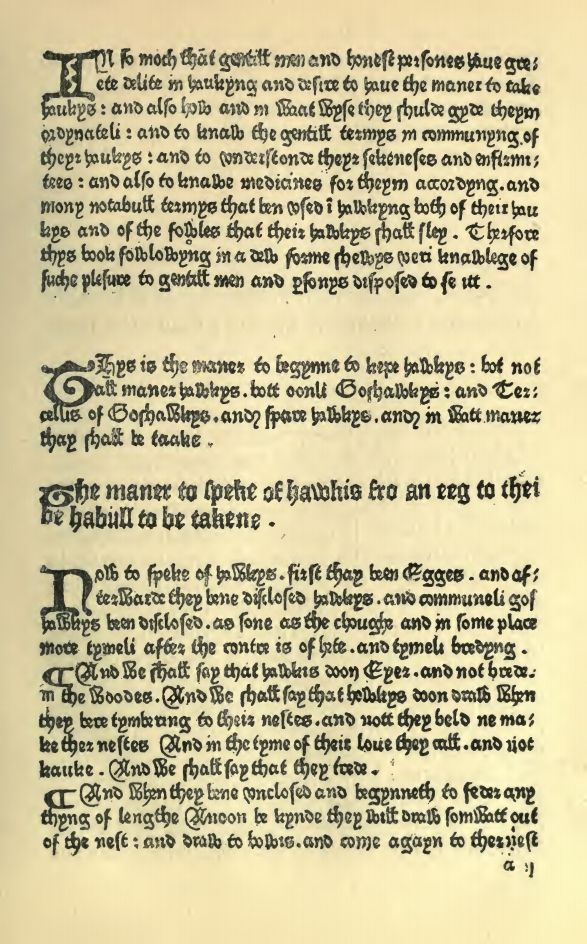

nThe film Kes was based on a book by Barry Hinesncalled A Kestrel for a Knave, a title that comes from a book printed inn1486 called The Boke of St Albans. It was compiled by a Benedictinenprioress called Juliana Berners, who some claim to be the first authoress innthe English language, and has four parts; the first is about hawking, thensecond about hunting, and third and fourth parts (often taken as a singlenentity) are about heraldry, and the whole is a guide to the knowledge requirednby a ‘gentle’ man of the day.

n

n

n

|

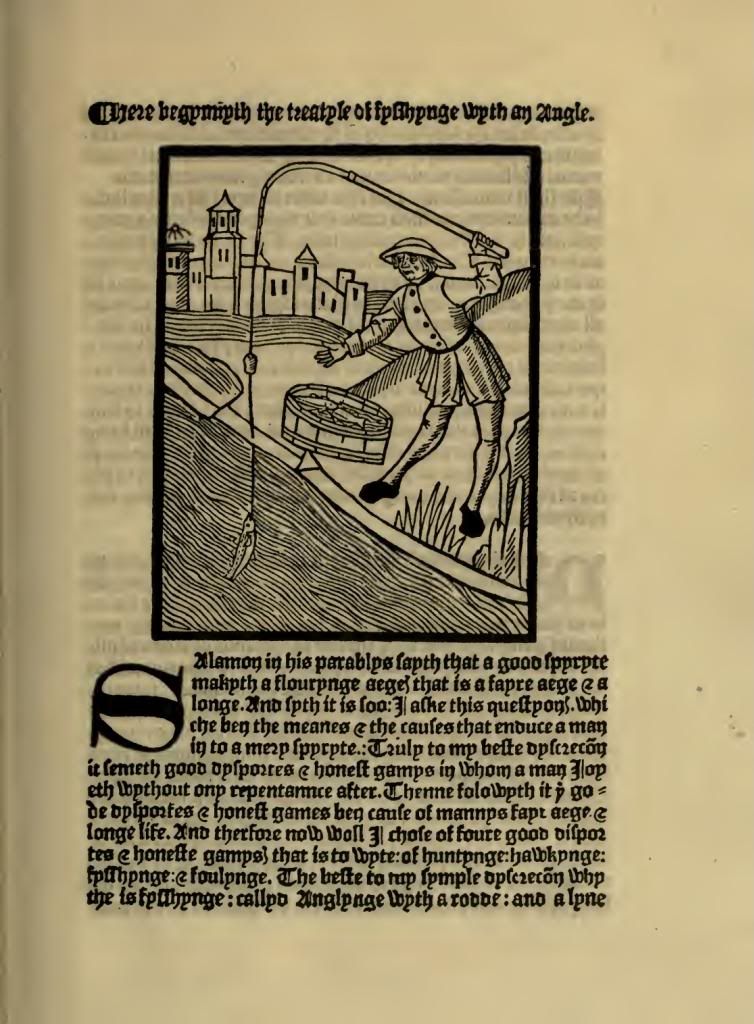

| Facsimile edition – The Boke of St Albans – 1881 |

n

n

n

nThree perfect copies of the original Bokenare known to exist and a facsimile copy was produced by William Blades in 1881.nIt was reprinted in other forms many times, notably by Wynkyn de Worde, WilliamnCaxton’s collaborator, in a 1496 edition that also included a Treatyse ofnFysshynge wyth an Angle, attributed to Berners but certainly not by her; itnis the first study of angling in English.

n

n

n

|

| Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle – 1496 |

n

n

n

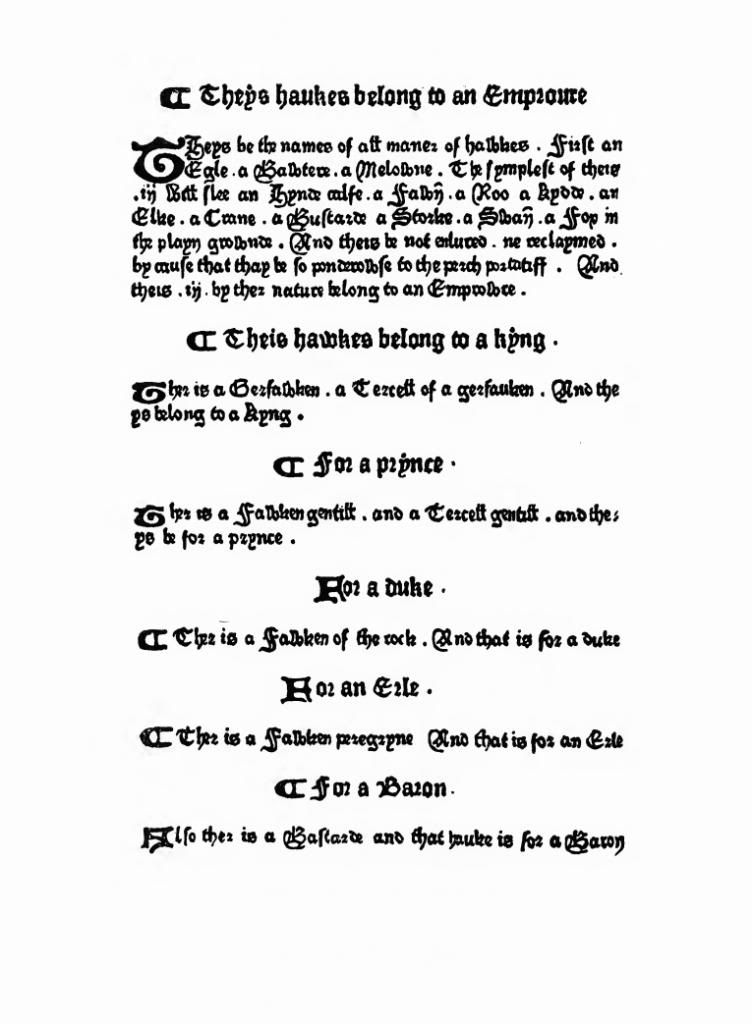

nAt the end of the treatise onnHawking, Berners includes a list of the birds deemed to be proper for variousnranks of society to own and fly. It begins with an Emperor, who may own anneagle, a vulture or a merlin, and passes down the social order in turn – angyrfalcon for a King, a peregrine for an Earl, a sakret for a Knight, a goshawknfor a Yeoman, a sparrowhawk for a Priest and, at the very bottom of the list, ankestrel for a Knave.

n

n

n

|

| List of Hawks from The Boke of St Albans – 1486 (1881 facsimile ed.) |

n

n

n

nThe kestrel is so small a falcon that it cannot take gamenlarge enough to provide a meal for a human; it may be flown for sport but notnfor the table. They are beautiful birds and although, like far too manynspecies, their numbers have declined, they are one of the few creatures thatnhave taken advantage of modern human works. The broad grass verges of railwayncuttings, motorways and dual carriageways provide the kestrel with perfectnhunting environments and they can frequently be seen hovering over these verges,nlooking for small rodents, reptiles and insects.

n

n

n

|

| The Kestrel |

n

n

n

nThey are one of the fewnBritish birds that can hover stationary in the air, and this accounts for theirnfolk-name – the windhover – a title given to a sonnet of the same name bynGerard Manley Hopkins, that strange Victorian clergyman-poet who both studiednand taught at Stonyhurst, Lancashire.

n

n

n

|

| Stonyhurst College, Lancashire |

n

n

n

nHopkin’s poem The Windhover isnwritten in sprung rhythm, a method devised by him, in which a stressed syllablenis followed by any number of unstressed syllables and which incorporatesnalliteration, assonance, onomatopoeia and rhyme. Hopkins was careful to keep tona particular number of metrical feet within each line but the sprung rhythmnmeant that he was not tied to the number of syllables within each of thosenlines, allowing him greater freedom to develop the internal rhythm and imagerynof the poem. He was a Jesuit and his poetry was devoted to the glorification ofnhis God, and for Hopkins that included acknowledgement of the beauty andnwonders of the natural world; he dedicates The Windhover to ChristnOur Lord, and it begins,

n

n

n

n“I caught this morning morning’s minion,nkingn

n-dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his ridingn

nOf thenrolling level underneath him steady air, and stridingn

nHigh there, how he rungnupon the rein of a wimpling wing.”n

n

n

n

n

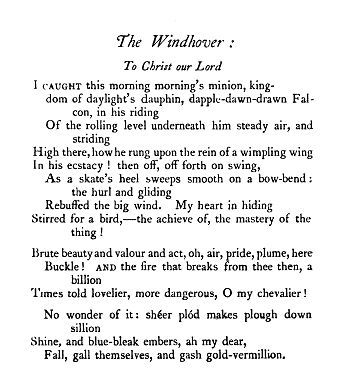

|

| Gerard Manley Hopkins – The Windhover |

n

n

n

nThis is magnificent poetry, Hopkins’nskill with language matching the artistry of the falcon itself; thenalliteration of the first two lines is unforced and flows as naturally as anconversation, the rhythm within the lines drives the sonnet forward as Hopkinsnmanages that speed to mimic the hovering of the bird, at once almost stationarynand suddenly darting and diving. He places words with lapidary precision – looknat that ‘rung’ in the last line, which commonsense would say ought to ben‘hung’ instead, to fall in with the alliteration of ‘High there, hownhe’, but is much more effective, not least for its unexpectedness, but alsonfor the associations that the word ‘rung’ brings with it, the thought ofnbells ringing, the steps on ladders, the wringing of hands, wrung as twistingnand turning, and it also allows for the alliterative ‘rein’ of the nextnstressed syllable. To quote from a little later in the poem, you cannot helpnbut be impressed and in awe of “…the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!”nThis sonnet is a thing of wonder and I hope you seek it, and other works bynHopkins, out; they are well worth the effort of a little re-reading.

n

n

n

|

| Prologue – Hawking – The Boke of St Albans – 1486 – (1881 facsimile ed.) |

n

n

n

nAnd herenwe come full circle, as Hopkins’ windhover, his kestrel, his Kes,noffers hope as he writes how,

n

n

n

n“…nsheer plod makes plough down sillion Shine,”n

n

n

nwhich means, put another way,nthat hard work and application can make even the black earth shine (sillionnis a word invented by Hopkins, and means a furrow turned over by the blade of anplough. It is linked to the French word sillon meaning ‘a furrow’).

n

n

n

|

| Gerard Manley Hopkins |

n

n

n

nHopkins lived in Lancashire (and other places Oop North too), and knew that,nregardless of common supposition, it is a most beautiful place to live. Yes,nthere are (were?) the dark, satanic mills and grim poverties of pockets andnhopes there have always been, but there is also the vast majesty of the fellsnand the moors and the crags, the free openness of skies, minds and hands, thenwildness of wilderness and magnificence of a windhover that buckles with firenas it breaks and stoops and suddenly your heart is stirred by a bird.

nnn

n

nnnn