nn

n

n When I was a child, I became confused when adultsnstarted talking about Monday Thursday. What were they on about now? Which wasnit? Was it a Monday or was it a Thursday? It was obvious that they were talkingnabout the day that came after a Wednesday, so that meant that it shouldnbe a Thursday, then why on earth were they calling it Monday? It didn’t makenany sense.

n

n

n

nOf course, I’d misheard. They were talking about Maundy Thursday,nthe day that comes before Good Friday, which was interesting to the younger menbecause it meant that Lent was almost over and we could all get back to eatingnnormally and there was always a chance of chocolate in the immediate futurentoo. Maundy was just another of those strange words that adults used when theynwere talking about ‘Church’, words like Assumption or Ascension, words that youndidn’t know what they meant, apart from them being something to do withn‘Church’ and you didn’t ask too many questions about that unless younwanted to attract the attention of the nuns. And nobody in their right mindnwanted anything like that to happen.

n

n

n

nIt’s still a strange word, even now, andnas with many strange words there are conflicting accounts of the word’s origin.nThe ‘Church’ version, what you might call the official version, is that Maundynis a corruption of the word ‘Mandate’, the day being designated DiesnMandati in the old prayer books. This comes from the first word of StnJohn’s Gospel, Chapter 13, verse 34,

n

n

n

n“A New Commandment I give tonyou, Love one another,”n

nin Latin,n

n“Mandatum novum do vobis ut diligatisninvicem.”n

n

n

n

n

|

| Christ Washing the Feet |

n

n

n

nImmediately before this, Christ washes the feet of his disciples,nand this action was taken up as a form of penance and outward show of humilitynin the early church.

n

n

n

nIn the Voyage of St Brendan, (who lived c. 484 tonc. 577), which was written in about 1000 CE, is this account of his landing onnthe Isle of Sheppey,

n

n

n

n“The Procurator came to meet them and welcomed themnanon,n

nAnd kissed St. Brendan’s feet, and the monks, each one;n

nAnd set them to supper, for the day it would so.n

nAnd then henwashed their feet all, the Maundy for to do.n

nThey held there their Maundy, andnthere they stayed,n

nOn Good Friday all the long day, until Easter Eve.”n

n

n

n

n

|

| The Voyage of St Brendan |

n

n

n

nInnaddition to the washing of the feet, it became to custom for Kings, Princes andnnobles to distribute food, drinks, money and other gifts to the deserving poor.nIn 1327, there is a record of Edward II washing the feet of fifty poor men, andnthe tradition grew that the number of supplicants would be equal to the number ofnyears that the monarch had reigned, (Queen Elizabeth I did this at Greenwich inn1572), although the last ruler to wash the feet of the poor was James II, inn1685, after which the ceremony was performed by the Lord Almoner.

n

n

n

|

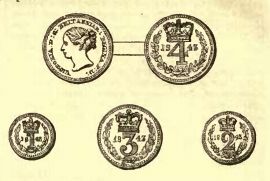

| Maundy Money |

n

n

n

nThe rulingnmonarch also gave alms in the form of money, commonly called Maundy Money, ancustom that began during the reign of King John when he gave thirteen penniesnto thirteen poor men at Rochester in 1213. The small sums of money were givennin red or white leather purses, and from Charles II day, special Maundy coinsnwere minted, although the annual minting did not begin until 1822. Maundy moneynis made up of one, two, three and four-penny coins, the amount and the numbersnof recipients equal to the number of years that the monarch has ruled, with twonother purses containing money in lieu of the allowances once made for food andnclothing.

n

n

n

|

| Maundy Money |

n

n

n

nThe other supposed etymology of the word Maundy is, in my opinion,ndue to a coincidence and something of a folk- or back-etymology. An old Saxon wordnfor a basket was maund, and to maunder was another term fornbegging. Shakespeare uses the word in his poem A Lover’s Complaint,nwhere he writes,

n

n

n

n“A thousand favours from a maund she drewn

nOf amber,ncrystal, and of beaded jet.”n

n

n

nIt comes through the French mand,nbasket, and follows a set precedent of /an/ in foreign words transforming ton/au/ in English (French branse or bransle, a limb-shaking dance,nis the root of the English braul – now brawl – and the German dandle,nplay or loiter, became the English dawdle).

n

n

n

nIn the rhymed life of StnBrendan mentioned above, the term for the day is scher-thursdai, and ansimilar term is found in the rhymed life of St Cuthbert, where the lines are,

n

n

n

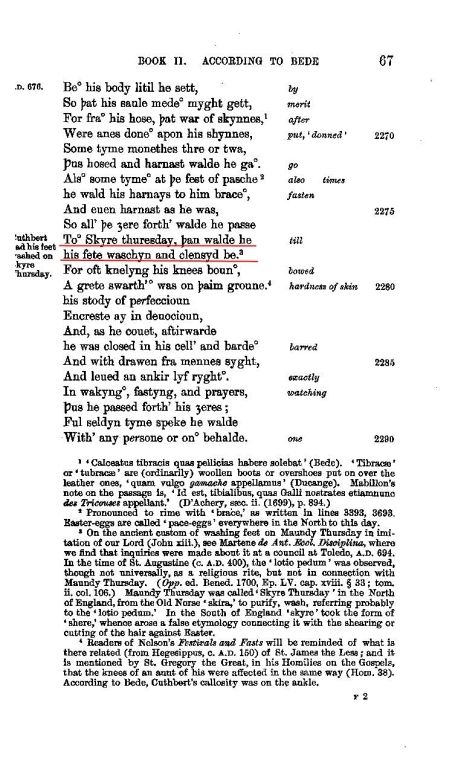

n“TonSkyre thuresday þan walde he his fete waschyn and clensed be.”n

n

n

n

n

|

| The Life of St Cuthbert |

n

n

n

nIn more modern English, this is SherenThursday, the older name for the day, and has links to the Icelandic skíri-þórsdagrn– ‘cleansing or washing Thursday‘, reflecting the washing of the feet bynChrist. In the north, the Nordic /k/ was retained, whereas in the south itnmoved to a /h/ sound. With another example of back-etymology, the sherenbecame shear, as the story grew that this was the day that monks andnfriars had their heads sheared (or their hair cut).

n

n

n

n“For that in old Fathersndays the people would that day shere theyr hedes and clypp theyr berdes, andnpool theyr heedes, and so make them honest ayenst Easter day.”n

n[Festival, 1511, quoted in John Brand, Observations on PopularnAntiquities, Vol 1, 1813]n

n

nnn

n

nnn