.

DeNiro goes to town in scenes that deserve immortality for describing exactly the necessary mind-set of a film executive, from his “just making pictures” monologue to Donald Pleasance’s out-of-his-depth English playwright, and his bitterly hilarious rant about the line “Nor I You” – indeed I’ve seen both scenes anthologised in documentaries on Hollywood – which probably reflects Fitzgerald’s difficulties in having his literary dialogue rubbished by studio authorities. The film captures the authentic flavour of a man who understands the nature of his medium and what he sells, being inextricable from what he craves as an American self-made man and simultaneous fantasist, in a way that most glib portraits of Hollywood ignore or elide.

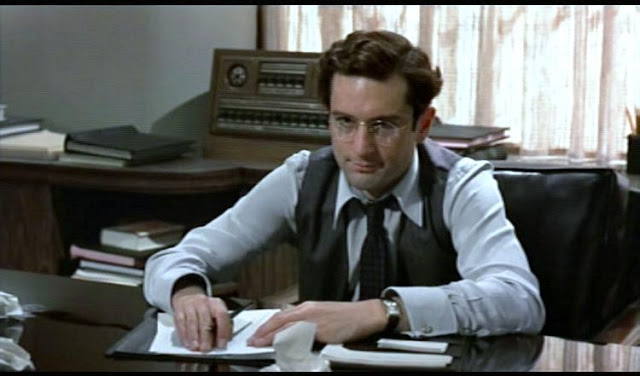

Elia Kazan, the premiere aesthete of obvious pseudo-naturalism, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, the quintessential moony romantic of American letters, could make for a threatening pairing, in theory. In practice, they meshed well. Kazan’s last feature film as director conveys Fitzgerald’s stardust-encrusted mythologic style within the stolid frame of his own, for once very restrained, approach, paring back unnecessary flourishes to stare Robert De Niro’s terrific Monroe Stahr right in the eye, and let him do the leading.

.

There’s not much story propulsion, as Kazan and screenwriter Harold Pinter can’t overcome the faults in Fitzgerald’s unfinished novel, which is textured by a series blackout story sketches, something that Pinter’s evasive style emphasises. But the portrait of a dynamic but haunted film wizard who chases illusory beauty off screen and something like honesty on screen, is intricate; Kazan plays the core movement, in which Stahr tries to romance a distant, sad English girl, Kathleen (Ingrid Boulting) who reminds him of his deceased screen siren wife, with the right mixture of poise and poetic intimacy to make it substantial.

DeNiro goes to town in scenes that deserve immortality for describing exactly the necessary mind-set of a film executive, from his “just making pictures” monologue to Donald Pleasance’s out-of-his-depth English playwright, and his bitterly hilarious rant about the line “Nor I You” – indeed I’ve seen both scenes anthologised in documentaries on Hollywood – which probably reflects Fitzgerald’s difficulties in having his literary dialogue rubbished by studio authorities. The film captures the authentic flavour of a man who understands the nature of his medium and what he sells, being inextricable from what he craves as an American self-made man and simultaneous fantasist, in a way that most glib portraits of Hollywood ignore or elide.

Boulting is affecting in a ridiculous part, part fragile, virginal sea nymph, part toff-accented femme fatale; one wonders whatever became of her. The rest of the cast is startlingly good, if not always used well, from Theresa Russell as the much more familiar bobbysoxer daughter of fellow executive Robert Mitchum, Tony Curtis as an impotent movie star, Jack Nicholson as a deep-red writer’s guild rep whom Stahr tries to take out his frustration on, and Dana Andrews as a director who can’t get to grips with imported star Jeanne Moreau.

.

I could not help but see this film, however, in terms of the texture of a nostalgia movement in ‘70s film for the movies of the past. Kazan’s evocations of that past don’t look so much like the movies of the Depression era so much as the other satires and riffs on old-Hollywood of the ‘70s, in films as diverse as What’s The Matter with Helen?, Play It Again Sam, Young Frankenstein, and Chinatown. The film-within-a-film segments have a kind of coffee-table photo-book perfection, more recreating the idea of old-Hollywood than the actual style of it, yearning for illusory glory days where illusion was a self-conscious choice, as opposed to the terms of ’70s pop culture when the last vestiges of Hollywood glamour and old-fashioned stardom were being vampirised by Airport movies and The Love Boat. Fitzgerald is tailor-made for nostalgists, but he was also writing about the harsh here-and-now. What he would have made of cocaine-fuelled ’70s Hollywood would have been very cool to see.