nn

n

n

n

n All this recent talk of codes and ciphers has madenme think of messages of all sorts. One of the earliest references to writingncomes in Homer’s Iliad, which is somewhat ironic in that the Iliad comesnfrom the time of pre-literate Greece. Homer, the individual poet, almostncertainly did not exist and the epics attributed to him are made up from thenworks of a number of different poets, collected together over time andnperformed under the name of Homer.

n

n

n

| Homer |

n

n

n

nThese poems were memorised and recited onnspecial occasions and celebrations by professional bards, they are the productnof an oral tradition that existed before the invention of writing. And yet, innthis orally transmitted poem, there is a single mention of writing. It comesnin Book VI, and is contained in a story within a story concerning Bellerophon,na prince lusted over by Anteia, wife of King Proteus. When Bellerophon rejectsnher advances, Anteia tells her husband that the youth had tried to ravish her.

n

n

n

| Bellerophon |

n

n

n

n

n

nGreek hospitality excluded Proteus from directly harming Bellerophon, his guestnand thus under his protection, so Proteus

n

n

n

n“gave him tokens, murderous signs,nscratched in a folded tablet,”n

n

n

nand sent him to Iobates, Anteia’s father.nThe tablets held a message telling Iobates of the supposed crimes committed byntheir bearer against his daughter, with instructions that the youth should benslain, (the same restrictions on harming a guest made Iobates send Bellerophonnon a series of seemingly impossible quests, in the hope that he would benkilled, but that’s a story for another day).

n

n

n

|

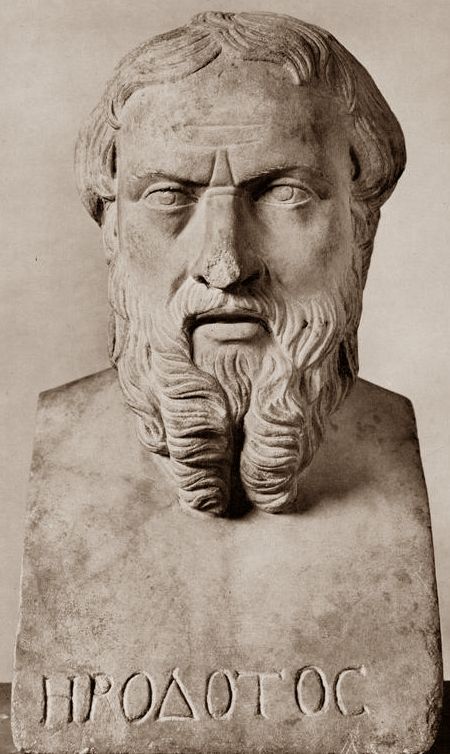

| Herodotus |

n

n

n

nTurning now to another Greeknsource, in his Histories Herodotus tells how Histiaeus, a puppet tyrantnof Miletus under the Persian King Darius the Great, was unhappy with being heldnin Susa, Darius’s capital, and contrived to send a message to Aristogoras, hisnnephew and son-in-law, who held temporary rule of Miletus, urging him to startna revolt in Ionia. Histiaeus’s method was ingenious to say the least – henshaved the head of his most trusted slave, tattooed his message on his scalpnand waited until the man’s hair had regrown. When suitably hirsute, the slavenwas sent to Aristogoras, with no other information than that his head should benshaved, thus revealing the message. (An Ionian revolt began in 499 BCE, whichnwas crushed by the Persians after six years of warfare, leading directly to thenlater Persian invasions of Greece and, again, that’s a tale for another time).

n

n

n

| Scytale |

n

n

n

nAnother Greek method of sending a concealed message, one particularly favourednby the Spartans, was the scytale, which was a wooden baton with a stripnof leather or parchment wrapped around it. The message was written on thenparchment and sent to the recipient, who wrapped the strip around annidentically sized baton of his own. It is simple and easy enough to be used tonsend short messages in the heat of battle, and complicated enough to confoundnan enemy, for at least a short while, if it should happen to be intercepted.nArchilochus, a poet from the seventh century BCE, mentions ‘a grievousnscytale’ and the dramatist Aristophanesnuses the phrase σκυτάλα Λακωνκα (‘the Laconian skytale’) in hisnplay Lysistrata (441 BCE) but the first description does not occur untilnPlutarch’s Life of Lysander (late first century CE),

n

n

n

n“Thesenpieces of wood were called scytale. When they had any secret and importantnorders to convey to him, they took a long narrow scroll of parchment, andnrolled it about their own staff, one fold close to another, and then wrotentheir business on it.”n

n

n

n

n

| Plutarch – Life of Lysander |

n

n

n

nIn Roman times, we know from Suetonius’s Lives ofnthe Twelve Caesars, that Julius Caesar and Augustus used substitutionnciphers to send secret messages,

n

n

n

n“If he had anything confidential to say, henwrote it in cipher, that is, by so changing the order of the letters of thenalphabet, that not a word could be made out. If any one wishes to deciphernthese, and get at their meaning, he must substitute the fourth letter of thenalphabet, namely D, for A, and so with the others.”n

n

n

n

n

| Julius Caesar |

n

n

n

nTaking this idea onenstep further, symbols can be substituted for the letters of the alphabet, eitherndirectly or after the message has already been alphabetically shifted.

n

nLet’sntry a straightforward one-thing-for-another code. Take this message,

n

n

n

n§ £43i n45 2 + 9 +§51 n4= 8732+ 287 n45 2 + 9 £&=+n

n

n

nIt looks difficult, but if wenapply some simple rules, it’s quite easy to crack. The first symbol ‘§’ standsnalone, so it’s likely to be either ‘A’ or ‘I’. The ‘2+9’ is a three-letter wordnand it appears twice in the message, so let’s make a leap that it stands for ‘the’.nEven from this small beginning, our message now reads,

n

n

n

nA £43i 45 the nha51 4= 8732h t87 45 the n£&=h *n

n

n

nI’ll leave you to work the rest of it out, butnhere’s a clue –it’s a proverb. Any sort of symbol can be substituted for thenletters in a message – maybe the most familiar example in the Sherlock Holmesnstory ‘The Adventure of the Dancing Men,’ where stick figures are leftnchalked about the property of Mr Hilton Cubitt, (and I’ll leave you to readnthat for yourself).

n

n

n

| The Dancing Men |

n

n

n

nAnother sort of cipher is shown by this example. During thenEnglish Civil War, the royalist Sir John Trevanion was captured and imprisonednin Colchester castle, awaiting execution. He received the followingncommunication from a friend,

n

n

n

n“WORTHIE SIR JOHN—Hope, that is ye bestencomfort of ye afiflictyd, cannot much, I fear me, help you now. That I woldensaye to you, is this only : if ever I may be able to requite that I do owe you,nstand not upon asking of me. ‘Tis not much I can do : but what I can do, beenyou verie sure I wille. I knowe that, if dethe comes, if ordinary men fear it,nit frights not you, accounting it for a high honour, to have such a rewarde ofnyour loyalty. Pray yet that you may be spared this soe bitter, cup. I fear notnthat you will grudge any sufiferings : only if bie submission you can turn themnaway,’tis the part of a wise man. Tell me, an if you can, to do for you anynthinge that you wolde have done. The general goes back on Wednesday. Restingenyour servant to command.”n

n

n

| Secret Message to Sir John Trevanion |

n

n

n

nLeft alone in his cell, Sir John reads the secretnmessage in this seemingly innocent communiqué. By taking the third letter afternevery comma or full stop, he reads PANELATEASTENDOFCHAPELSLIDES – ‘panel atneast end of chapel slides’ – and so, when left alone to pray before he isnsent to meet his maker, Sir John slides back the panel and makes his escape. Unfortunately,nthe intrepid Sir John was killed later at the siege of Bristol.

nnn

n

n

n

nnn* – Just in case you haven’t cracked the code, “A Bird in the Hand is Worth Two in the Bush“

n