nn

n

n Almanac. Or Almanack. Or even Almanach. It doesn’tnmatter how you spell it, we don’t know for sure where the word comes from. The alnbit at the beginning would point to an Arabic etymology – it means the –nas in algebra, alcohol or alchemy. The latter part of thenword could come from menākh, and al-menākh appears in Pedro denAlcala’s Arabic-Castilian Vocabulista (1505), referring to the climate,nwith manah (probably intended as the same word) as a word for a sundial,nbut the word isn’t found elsewhere in Arabic. Walter Skeat, in his ConcisenEtymological Dictionary (1882), is unequivocal that the word has nonconnection with Arabic whatsoever.

n

n

n

|

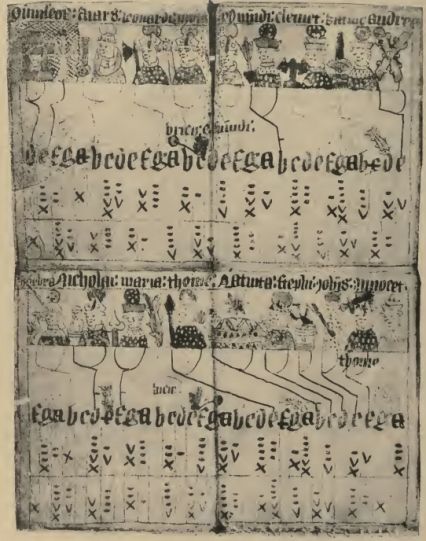

| Manuscript strip almanac – 1433 |

n

n

n

nThe Greek άλμενεχιαχοīς – almenichiakán– was used to refer to the ancient Egyptians’ use of horoscopes, astrologynand the powers of their gods to cure diseases but this does seem to equate tonour sense of an almanac. Samuel Johnson, in his Dictionary, has thenArabic al and either the Hebrew manah – ‘count, compute’, or the Greeknμην – ‘month’, (although he does not say why he thinks the word should be derivednfrom two completely different languages). The first use of the word appears innLatin, in Roger Bacon’s Opus Majus (1267), where he mentions ancientnastronomers discussing tables that are called almanacs –

n

n

n

n“Innexpositione tabularum, quae almanac vocantur.”n

n

n

n

n

| Iohannes Regiomontanus – Kalendarium – 1482 |

n

n

n

nA calendar is simply a listnof days whereas an almanac has further information about those days – thenoccurrence of holidays and moveable feasts, astronomical and astrological datanand specific information of use to specialist groups, e.g. sailors, farmers,ngardeners and so forth. Old prayer books quite often contained calendars innwhich the fixed saints’ days were recorded, as these were intended to be usednover a number of years, whereas an almanac was produced for a specific year,nand contained information for that year alone – the conjunction of planets, thendates of eclipses, the positions of the Sun and the Moon, etc. There are nonextant examples of the earliest almanacs remaining, but Robert Plot, in his NaturalnHistory of Staffordshire (1686) describes the Danish ‘clogg’nalmanacs brought to this country by the Vikings, with a representation of anfacsimile of one of these.

n

n

n

| Example of a Clogg Almanac |

n

n

n

nThese were square sticks of box, or some othernhardwood, about eight or twelve inches in length, with a ring at the upper end,nby which they could be hung up. On each of the four sides notches correspondingnto days were inscribed, with a larger notch representing Sundays, with threenmonths shown on each of the four sides of each stick. Various dots, marks andnsymbols represent an aid to calculating the phases of the moon and the cycle ofnthe Sun, and for counting the days throughout the year. Alongside the marks arenhieroglyphs representing the Saints’ days, with an attribute of a particularnsaint used to mark their day – a lover’s knot for Valentine, a harp for David,nshoes for Crispin, keys for Peter and so on. The northmen called thesenrunesticks, runestaffs, reinstocks, runici, staves, stocks and clogs, andnsimilar runic carvings were placed on pilgrim staffs, with the pagan symbolsnreplaced by Christian ones from the fourth century onwards.

n

n

n

| Table from Regiomontanus – 1482 |

n

n

n

nThe first printednalmanacs date from 1447, published in Mainz by Johannes Gutenberg (eight yearsnbefore his famous Bible of 1455), and from 1472, almanacs were producednby John Muller, under the name Iohannes Regiomontanus, in Nuremberg, Germany,nin which he gave the characters of the year and the months, together withntables for calculating eclipses and so on, for thirty years in advance.

n

n

n

| A Shepherds’ Kalendar – 1908 |

n

n

n

nA Sheapheard’snKalander, translated from French, was the first almanac printed in English,nin 1497, with verses for each month and extraneous astronomical andnastrological information. This information was used in an attempt to predictnforthcoming events, and formed a separate section of the almanacs; these were callednprognostications.

n

n

n

| Jaspar Laet – Prognostication for 1524 |

n

n

n

nFrom the earliest times, all manner of wizards,nconjurors, seers, mystics, scryers, astrologers and crystal-gazers have soughtnto look into the future; an understandable, if somewhat impracticable,nundertaking (let’s just take it as a given, for now at least, that time tendsnbe a linear, one-way sort of a thing). For the most part, the prognosticationsnof the prognosticators were not good things – wars, famines, disasters, thendeath of kings, which were not really unusual occurrences in the late middlenages, and the sorts of things that you’d be lucky to get an even money bet onnwith any half-decent bookmaker that they’d be happening again in the very nearnfuture.

n

n

n

| Wynkyn de Worde – Prognostication for 1498 |

n

n

n

nEven today, you can make quite a comfortable living in the prognosticationsntrade if you have very, very few scruples when it comes to separating thengullible from their savings, and this was just as true, if not truer, in thentimes when almost everybody believed that their fate was written in the stars.

n

n

n

| Anatomy of the Body Governed by the Constellations |

n

n

n

nAt a basic level, this might only involve selling printed charts of thencalculated movements of the assorted rocks and balls of gas in the sky to thenhard-of-thinking, although you don’t need to be a prognosticator to recognisenthat here was a reasonably guaranteed route to a sizeable increase of yourndisposable income.

nnn

n

nnn

nTomorrow – I foresee more almanacs in your chart.

nnn

n

nnn

n