nn

n

n I’ll chuck my hat into the ring and add to the listnof ‘what is it that oils the wheels of society’ by saying that, in mynopinion, manners provide that necessary lubricant. Wait a minute though, younwould say that, you might counter, you’re an Englishman after all and what elsenwould you say? However, unlike the language of flowers, or the acrostics ofngemstones, manners are another code that you can’t really opt out of, (well,nyou can, but if you’re English, that’s only going to lead to someone, sometime,ntutting at you – maybe, just maybe, when you are still in the room).

n

n

n

|

| Curtseying |

n

n

n

nPeople mayncall it etiquette, and have done so for over 250 years, but before wenstole a French word for it, we called it courtesy (and, yes, I know thatncomes from Old French roots, but that’s because after 1066, and for the nextnthree hundred years or so, the French were running the show on this side of thenChannel). We called it that because it was the sort of proper behaviour thatnyou’d expect to find in a royal court, pretty much in that same way thatnchivalry is the behaviour you’d expect from a chevalier, ornknight. If everyone knows the rules, and sticks to them, then everything turnsnalong nicely, thank you very much, and there are no nasty surprises.nIncidentally, in the sixteenth century, that short medial ‘e’ in the word wasnoften elided, and the word was pronounced as Court’sy, from which we getnthe name of something that you’d often see at court – a curtsey.

n

n

n

|

| Caxton – The Boke of Curtasye – 1477 |

n

n

n

nOne ofnthe earliest books ever printed in the English language is William Caxton’s ThenBoke of Curtasye, (1477), showing that back in the fifteenth century therenwas a ready market for a guide to social behaviour and manners. Caxton’snpointers still sit well today – comb your hair, keep your ears clean, don’tnpick your nose and so forth, and he has a long section on table manners, whichnwere obviously an area where people needed a bit of instruction, and henconcludes his advice with a section on which authors should be read by anwell-bred young fellow (hardly surprising that, from a publisher who printednmost of the works he recommends).

n

n

n

|

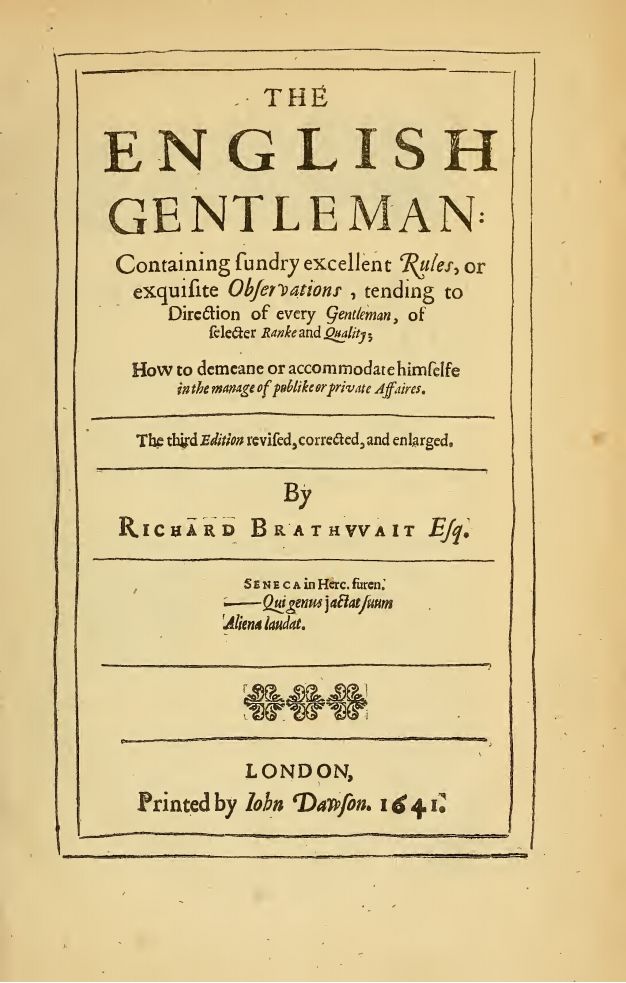

| Richard Braithwaite – The English Gentleman and English Gentlewoman – 1631 (3rd Ed. 1641) |

n

n

n

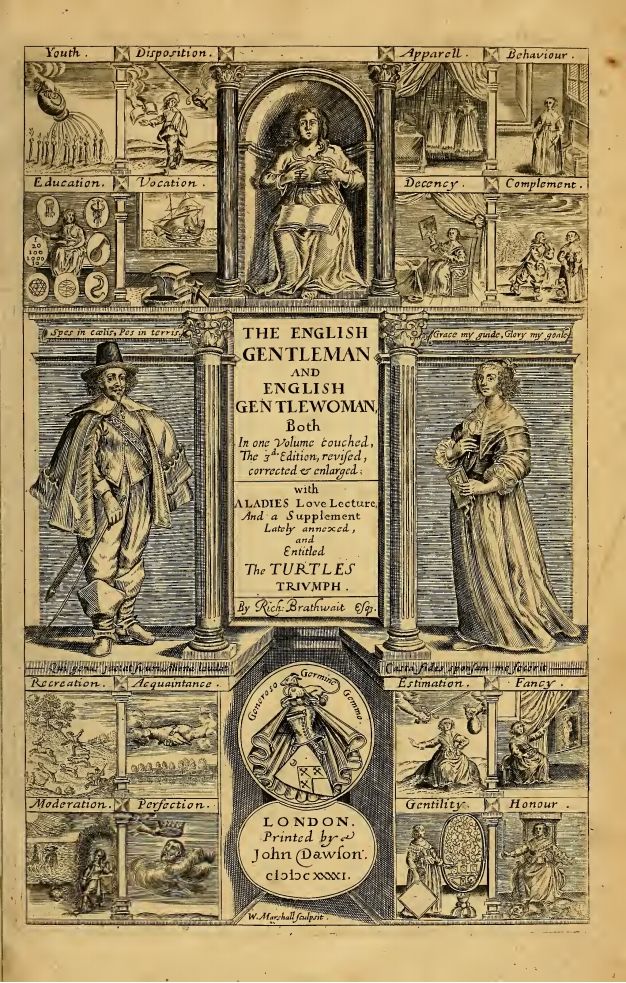

nBy 1631, Richard Braithwaite had expanded thenfield with his The English Gentleman and The English Gentlewoman, whichnadvocated an entire philosophy of life, encompassing disposition, apparel,neducation, recreations, honour and fancy, rather than telling you not to blownyour nose on the tablecloth, and as a practical guide to manners leaves much tonbe desired.

n

n

n

n

n

|

| William Darrell – The Gentleman Instructed – 1704 (10th Ed. 1732) |

n

n

n

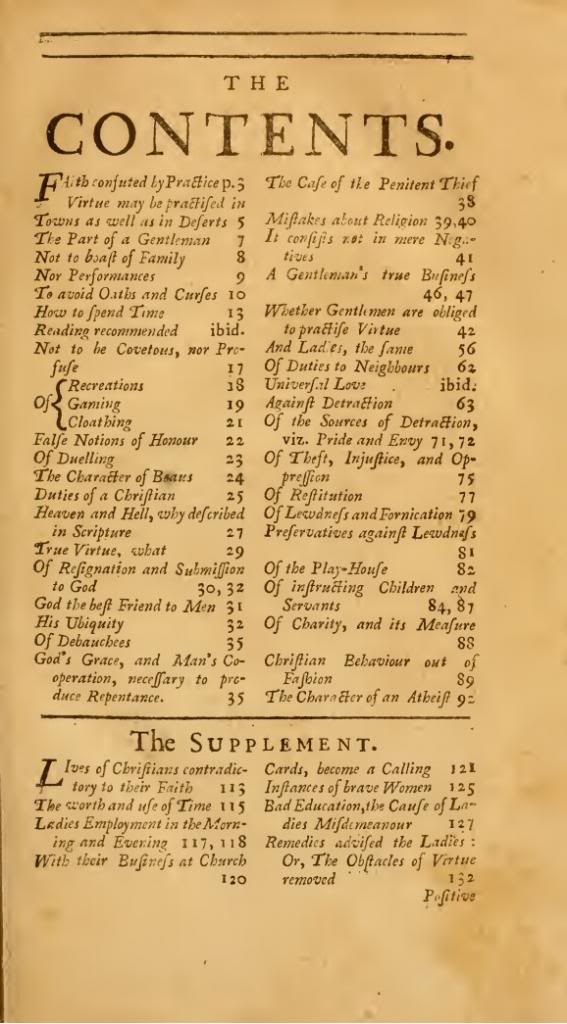

nIn a like manner, William Darrell’s The Gentleman Instructedn(1704), which takes the form of a dialogue between Neander, a young man seekingninstruction, and Eusebius, his tutor in matters worldly, concerns itselfnlargely with the moral and spiritual education of its protagonist and itsnpractical advice is limited to don’t get drunk, don’t gamble, don’t hang aroundnwith mucky women or atheists, don’t go to the theatre and live in fear ofneternal damnation, God’s wrath and your dangly bits falling off.

n

n

n

|

| William Darrell – The Gentleman Instructed – 1704 (10th Ed. 1732) |

n

n

n

nThe point ofnthe early courtesy books was to prepare young middle- and upper-class boys fornlife at the royal courts. Excluded from trade and other jobs, in times of peacenthere were only three realistic routes open to these boys; the Law, the Churchnor the Court, (as for girls, their only future lay in a good marriage). It wasnthe custom of wealthy and powerful men to take a number of boys into theirnhousehold, to be raised as pages, cup-bearers or ‘henchmen’ (originally, anhenchman, or hengestman, was a groom, from Old English hengest – anstallion, horse or gelding). These boys were expected to learn tablenmanners, riding, fencing, music, languages and ‘casting accounts’ (basicnhousehold finance), and were given extra instruction from works like Erasmus’s PietasnPuerilis (1530), which is a curious blend of Classical maxims and courtesynbook (more of the ‘don’t pick your teeth, don’t chew with your mouth opennand don’t peer into your hankie when you’ve blown your nose’ stuff).

n

n

n

|

| Richard Braithwaite – The English Gentleman and English Gentlewoman – 1631 (3rd Ed. 1641) |

n

n

n

nThenreal change came when social mobility took off following the IndustrialnRevolution, when it became possible for the base-born to make fortunes innmanufacturing or trade. These parvenus, arrivistes and the nouveaunriche had not received the graces needed to allow them to take their placesnalongside those born into rank and privilege, and crash courses were needed tonbring them up to snuff, (and, as you see by the French terms used to describenthem, there was also a language barrier to contend with, too). The problem was,nin using manners as a tool for social exclusion, those responsible were guiltynof being bad mannered themselves, as snobbery is just as socially unacceptablenas spitting in the street, queue jumping or buying the Daily Mail.

nnn

n

nnn

n

nnn