nn

n

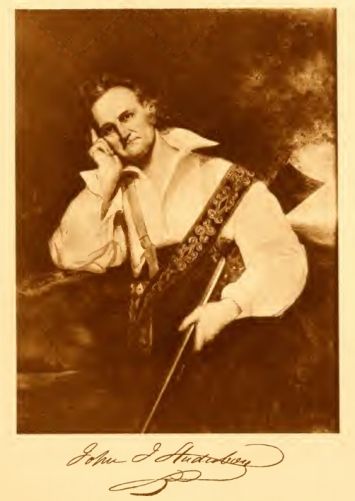

n He was a stranger in a strange land, but withncharacteristic resolve John James Audubon applied himself to his task. He hadnletters of introduction from America and he soon made the acquaintance of thenbest men of arts, letters and science in England, including Sir Walter Scott,nHumphrey Davy, Thomas Lawrence and Robert Bakewell (his wife’s cousin). Withinna week of landing at Liverpool, Audubon was in London, exhibiting his drawingsnat the Royal Institution, which earned him over a hundred pounds in admissionnfees. Lord Stanley declared that,

n

n

n

n“This work is unique, and deserves thenpatronage of the Crown.”n

n

n

n

n

|

| John James Audubon |

n

n

n

nAudubon himself cut quite a dash with his longnhair, dressed with bear grease, his unfashionable clothes, his abstemiousnhabits of food and drink, and his natural courtesy and down to earth manners.nEverywhere he went, he was well received and found support for his plan tonpublish his drawings in full size, and he began to collect names of thosenwilling to subscribe. He travelled to Manchester, from where he paid a visit tonBakewell, his wife’s family home, back to Liverpool and then on to Edinburgh.

n

n

n

nHere, he found himself in his element and began to feel that success was withinnhis grasp. Professor Robert Jameson did much to popularise Audubon’s work, andnrecommended it to the University. He was lionised in the newspapers, so much son

n

n

n

n“… that I am quite ashamed to walk the streets.”n

n

n

nThe Institution Hallngranted him free use of their rooms and insisted that a shilling admission bencharged, all of which would be paid directly to him, thousands of enthrallednvisitors gladly paid to see the 400 drawings, depicting over 1,000 differentnspecies. He was wined and dined, at the St Andrew’s Day banquet given by thenRoyal Society of Antiquarians he was so overcome by the praise heaped upon himnthat

n

n

n

n“…the perspiration poured from me and I thought I should faint.”n

n

n

nHenwas made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and of the Society ofnAntiquarians, he was elected a member of the Wernerian Society of NaturalnHistory and also of the Society of Arts. A letter of introduction to PatricknNeill brought an introduction to William Home Lizars, a distinguished Edinburghnengraver, and when Audubon took the first of his drawings from his portfolio,nLizars jumped up out of his chair and exclaimed,

n

n

n

n“My God, I never sawnanything like this before!”n

n

n

n

n

|

| J J Audubon – Great Footed Hawks (Peregrine Falcons) |

n

n

n

nBut it was when he saw the drawing of the GreatnFooted Hawks (Peregrine Falcons) that he declared his intention of engravingnand publishing Audubon’s works, in full size, in volumes of double elephantnsize (40 inches by 27 inches). A specimen volume would be produced first and onnNovember 10th Lizars began his engraving; on November 28thn1826, he handed Audubon the first proof of the Wild Turkey, produced in lifensize to justify the decision to print at such a large size.

n

n

n

|

| J J Audubon – Wild Turkey |

n

n

n

nBy December 10th,nLizars had finished the second plate, Yellow Billed Cuckoos in a papaw tree,nwith the male seizing a swallowtail butterfly, and over the next few weeks antotal of ten plates were made. These, when publicly displayed, were annastonishing success. Subscriptions began to flood in, from EdinburghnUniversity, the Countess of Morton and other distinguished collectors. However,nAudubon was still concerned, he was now into his forties and he estimated thatnit would take a further sixteen years to complete his ambitious project.

n

n

n

|

| J J Audubon – Yellow Billed Cuckoos |

n

n

n

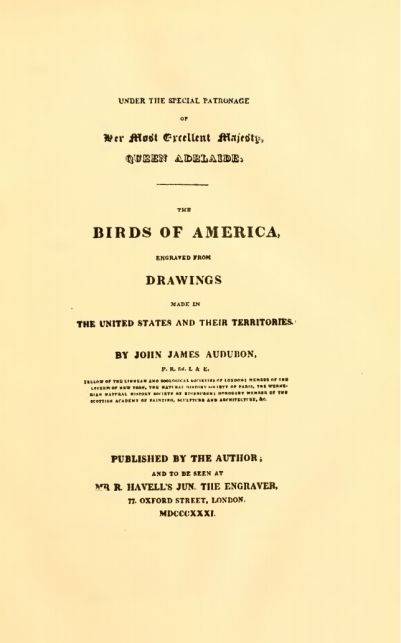

nNevertheless, at the end of March 1827, he issued his first formal prospectus,nthat the works would be issued in instalments of five double elephant plates,non the finest paper, five times per year, at a cost of two guineas perninstalment. From Edinburgh, he departed on a tour to gain subscriptions, firstnby stage to Newcastle (where he met Thomas Bewick, the eminent wood engravernand ornithologist), then to York, Leeds, Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham,nOxford and back to London.

n

n

n

|

| J J Audubon – Osprey |

n

n

n

nBack in the capital, he met John George Children,nSecretary of the Royal Society and head of the Department of Zoology of thenBritish Museum, and through Children Birds of America was presented tonKing George IV, thus allowing Audubon to announce that his book was beingnissued

n

n

n

nUnder the Particular Patronage and Approbation of his Most GraciousnMajestyn

n

n

n

n

|

| Prospectus for Audubon’s Birds of America |

n

n

n

nThrough the assistance of Children and Lord Stanley, Audubon wasnalso elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society, an honour that he valued morenthan any other of the many showered upon him. But, this being John JamesnAudubon we are considering, not everything went to plan, for he had not been innLondon long when Audubon received a communication from Lizars in Edinburgh. Thenworkers employed to colour the engravings had gone on strike, and by readingnbetween the lines, Audubon believed that Lizars was about to renege on hisncontract.

n

n

n

|

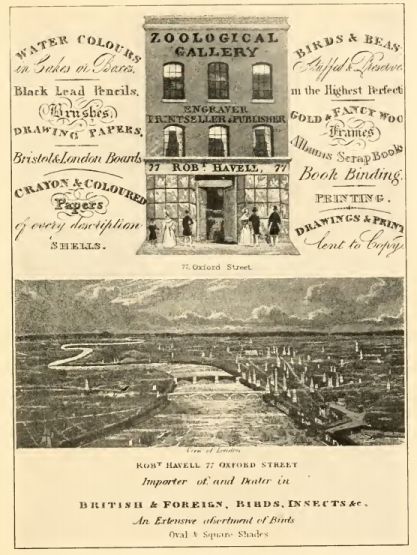

| Advertisement for Havell and Son |

n

n

n

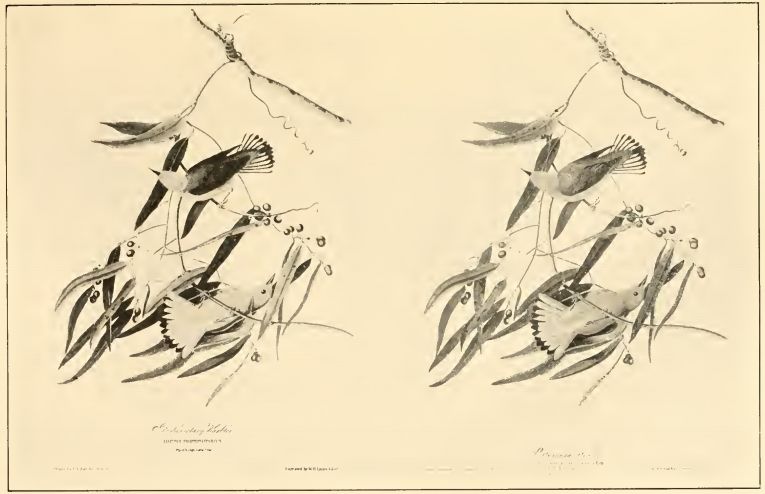

nConsequently, he scoured London in the search for a replacement fornthe Scots publisher, and eventually came across Robert Havell Jnr. who agreednto complete the colouring of the sheets already printed by Lizars and tonundertake a sample engraving made from one of Audubon’s drawings of thenProthonotary Warbler.

n

n

n

|

| J J Audubon – Prothonotary Warblers |

n

n

n

nThe result far exceeded Audubon’s expectations, and henpassed the entire operation over to Havell, with young Havell undertaking thenengravings, his father to do the printing, and the Senior and Junior Havells tonsupervise a team of colourists, who would hand tint the prints, with Audubon overseeingnthe entire work personally.

nnn

n

n

|

| Prothonotary Warblers – by Lizars (left) and Havell (right) |

n

n

nnn

nTomorrow – How could anything possibly go wrong?

nnn

n

nnn

n