nn

n

n

n

n Even before her accession to the throne of GreatnBritain, Victoria was the most eligible spinster in Europe. Several RoyalnHouses sought her hand for their assorted Princelings but it was Victoria’s ownnuncle, King Leopold I of Belgium, and her mother, Princess Victoria, (sister ofnLeopold), who arranged for the young Victoria to be introduced to her Germanncousins, Ernest and Albert, Dukes of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. It was hoped,ninitially, that Ernest, the elder brother by fourteen months, might prove to benattractive to Victoria but although they were temperamentally alike, she foundnhim ‘plain’. Albert, on the other hand, caught her eye, particularly on hisnsecond visit to England, and although the young Queen had actively avoidednbeing pushed into an early marriage, she proposed to him on October 15thn1839 and they were married on February 10th 1840.

n

n

n

|

| Queen Victoria in her wedding dress |

n

n

n

nVictoria andnAlbert were the same age, both born in 1819 and, interestingly, the samenmidwife had assisted at both births. At first, Albert was not at all popular innEngland. He was seen as just another minor European royal from an insignificantnlittle state no bigger than most English counties, impoverished and a German tonboot. Victoria’s early popularity was on the wane, she interfered in politics,nnever a good thing for monarchs to do, she had a mind of her own, again not angood thing for a monarch, and furthermore she was a woman and a Germannto boot.

n

n

n

|

| Prince Albert |

n

n

n

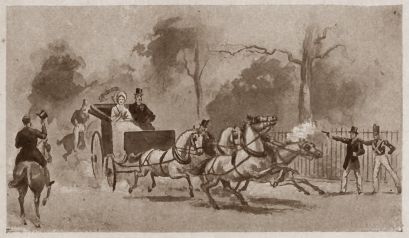

nAt six o’clock in the evening of June 10th 1840, Victorianand Albert were riding in a phaeton, an open, four-wheeled carriage drawn bynfour houses, out from Buckingham Palace turning left up Constitution Hillntowards Hyde Park. Victoria was sitting on the left side, Albert was on hernright side, and after the carriage had travelled about one hundred and fifty yardsnit passed by some iron railings at the bottom of Constitution Hill, when anyoung man standing by them, about five yards from the phaeton, drew a pistolnfrom his coat, fired a shot at the Queen, turned and looked behind himself,ndrew another pistol from under his coat, turned back towards the carriage andnfired another shot at the Queen.

n

n

n

|

| Shots fired at the Queen |

n

n

n

nVictoria was looking in the opposite directionnat the time and had not realised what was happening. Albert had seen the mannand drew his young wife down beside himself, the second shot passing over theirnheads. Joshua Lowe, a spectacle-maker, grabbed the shooter by both arms andnLowe’s nephew, Albert, took the pistols from him. Another man, William Clayton,nseeing the pistols in Albert’s hands, cried, “You confounded rascal, howndare you shoot at our Queen?” and took them from him, thinking him to benthe assassin. The real shooter, hearing this, shouted, “It was I, it was menthat did it,” but the rapidly assembling mob saw the guns in hisnhands and roughly seized Clayton, and took him to the police station. The Lowesnand Samuel Perks, another witness, manhandled the real shooter to the samenpolice station in Gardner’s Lane, where he was taken into custody.

n

n

n

n

n

|

| Queen Victoria |

n

n

n

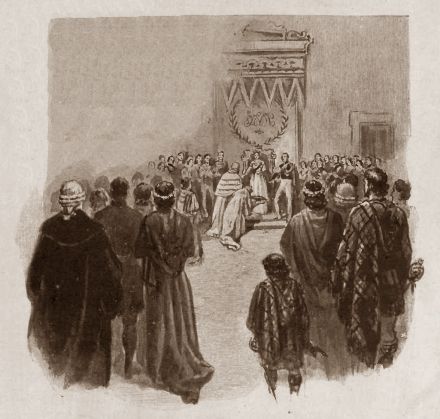

nBack inntheir carriage, Albert took Victoria’s hands into his own and asked if thenfright had shaken her, to which she replied with a reassuring laugh, and thennshe stood up, to show the crowd she was unhurt. She then ordered the coach tondrive at speed to her mother’s house in Belgrave Square, to anticipate anynexaggerated rumours that might reach her, before resuming the drive in GreennPark, where a great crowd accompanied the Royal couple, with enthusiasticncheers. All the equestrians on Rotten Row formed a guard of honour and escortednthe carriage around the park and back to Buckingham Palace, where for many daysnthey returned and loyally escorted their sovereign on her rides. The Queen,nalthough pale and shaken, bowed and waved to her subjects as she returned tonthe Palace, but when she got to the safety of her own rooms, she burst intontears. In all the theatres that night ‘God Save the Queen’ was sung withnunrestrained enthusiasm, both Houses of Parliament rode, in full dress, in twonhundred carriages to the Palace, where their address of congratulations wasnreceived by the Queen seated on the throne in state.

n

n

n

|

| Queen Victoria’s Court |

n

n

n

nTwo days later, a concertnwas given at the Palace, where the Queen herself sang five numbers, including anduet with Albert. Her bravery, cool-headedness and composure brought about anre-evaluation of her reputation, and a new spirit of patriotic loyalty to thencrown was fostered in the country. It was announced soon after that she wasnpregnant with her first child, which bolstered the sympathetic feelings towardsnthe couple, and there was also the realisation that if the assassinationnattempt had succeeded, the crown would have passed to Victoria’s uncle,nErnest Augustus I, King of Hanover, and so the country breathed a sigh ofnrelief.

n

n

n

|

| Prince Albert |

n

n

n

nAs a consequence, a Regency Act was passed almost unopposed, whichnnamed Albert Regent should Victoria die leaving an infant heir, providing hencontinued to reside in the country and did not remarry a Catholic bride. AsnRegent, Albert attended ceremonial events seated beside Victoria, his name wasnincluded in the Liturgy, he was admitted to the Privy Council and he receivednthe freedom of the City of London.

n

n

n

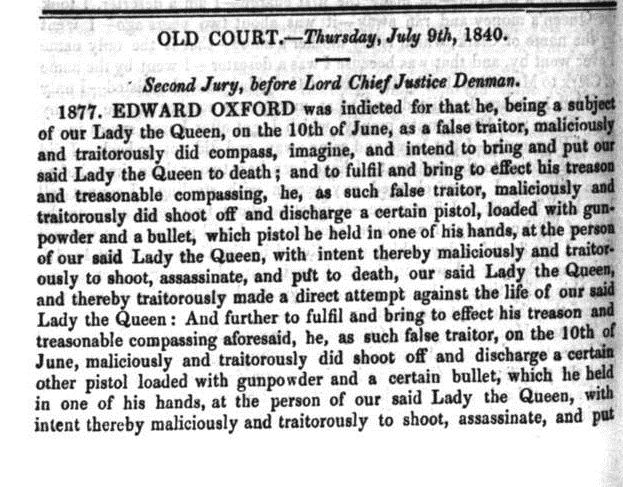

nThe would-be assassin responsible for thisnturn around in the fortunes of Victoria and Albert was one Edward Oxford, anneighteen-year-old potboy, who had recently been sacked from thenHog-in-the-Pound pub in Oxford Street. He had been born in Birmingham, thengreat-grandson of an Antiguan slave, into a family known for mentalninstability, and was tried for treason at the Old Bailey on July 6thn1840. He claimed that the pistol had not been loaded with shot, although policenwitnesses gave evidence that bullet marks had been found on brickwork at thenscene.

n

n

n

|

| Trial of Edward Oxford – Proceedings of the Old Bailey |

n

n

n

nThere were attempts to implicate Oxford in an anarchist plot but goodnsense prevailed and he was found not guilty of High Treason on grounds onninsanity and committed to Bethlem Royal Hospital for the Insane, before beingntransferred to the new Broadmoor Hospital in 1864. He was, by all accounts, annexemplary prisoner who exhibited no outward signs of madness, and during hisnlong incarceration he learned the skills of a house painter. It was felt thatnhis motive had been an adolescent desire for notoriety at any cost, and in laten1867, he was released on condition that he emigrate to Australia. He lived innMelbourne under the name of John Freeman, worked as a house painter and rose innsociety when he married a wealthy widow twenty years his junior. He became anchurchwarden at Melbourne cathedral and an author, writing newspaper articlesnand a book, Lights and Shadows of Melbourne Life (1888), before dying there inn1900.

n

n

n

|

| John Freeman – Lights and Shadows of Melbourne Life – 1888 |

n

n

n

nEdward Oxford was the first, but not the last, person to make an attempt on the lifenof Queen Victoria.

nnn

n

n

nnn