In the early hours of January 27, 1829, a notorious figure named William Burke was smuggled from his condemned cell. The police feared that if he was taken to the Law Market for his execution, a riot would break out. The crowd was eager to tear him apart. To prevent chaos, Burke was moved to a lock-up in Liberton’s Wynd.The Skeleton of William Burke8

A Gathering Storm

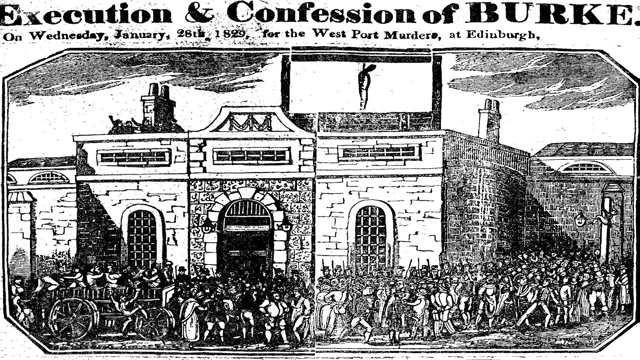

By noon on the day of his execution, preparations were underway at Lawnmarket. Strong poles and chains were set up to control the expected crowds. As news spread, people began to gather. They stayed throughout the day and into the night, braving heavy rain. At half past ten, they cheered as the gibbet was raised. By two in the morning, the crowd had taken their positions, determined to secure a good view of the event.

By 7 a.m. on January 28, around 25,000 people had assembled. They were willing to endure discomfort just to witness the execution. Many had even rented windows overlooking the Law Market days in advance, paying between five and twenty shillings.

Burke’s Final Hours

Meanwhile, Burke spent most of the night sleeping. He woke up at five, dressed in a black suit, and received visits from both Catholic and Protestant ministers. After praying with them, he asked to have his shackles removed. As the chains fell away with a loud clang, he dramatically declared, “So may all my earthly chains fall!”

Burke was then taken to a keeper’s room, where he sat by the fire, sighing occasionally. On his way to the scaffold, he encountered Williams, the executioner. “I am not just ready for you yet,” Burke said, waving him away. But Williams followed him and pinned his arms. Burke was offered a glass of wine and raised a toast: “Farewell to all my friends.”

The Procession to the Scaffold

Supported by a Catholic priest and led by two bailies, Burke made a solemn procession from the prison to the scaffold. The crowd jeered and hurled insults. Burke quickened his pace, fearing they might break through and harm him. As he climbed the steps, shouts of “Burke him!” and “No mercy, hang him!” echoed through the Law Market.

Burke knelt to pray, momentarily hidden from the crowd. They began to chant for Hare, his accomplice, and called for the execution of Knox, another figure associated with their crimes. After rising, Burke picked up the silk handkerchief he had knelt on, folded it neatly, and placed it in his pocket.

Facing Williams, Burke remained calm as the noose was placed around his neck. He only spoke once, saying, “The knot is at the back,” when Williams struggled with his neckerchief. A white cotton nightcap was pulled over his face, and he began to recite the Creed. At the words “Lord Jesus Christ,” the prearranged signal, Williams pulled the lever, and Burke dropped into the void.

The Crowd’s Reaction

As Burke struggled, the crowd jeered and yelled. He kicked and twitched, desperately seeking a platform beneath him. The undertakers below grabbed his legs and spun his body until it was level with the gallows. The drop occurred at 8:15 a.m., and his body was left hanging until 8:55 a.m. when Williams cut him down.

The crowd surged forward, eager to claim souvenirs. Police held them back as souvenir hunters sought pieces of the rope and shavings from the coffin. Once Burke’s body was secured in a box, the crowd dispersed. Despite being the largest gathering in Edinburgh’s history, there were no incidents.

Scientific Examination

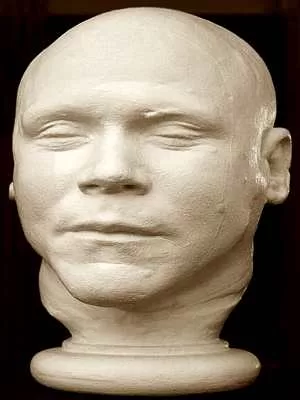

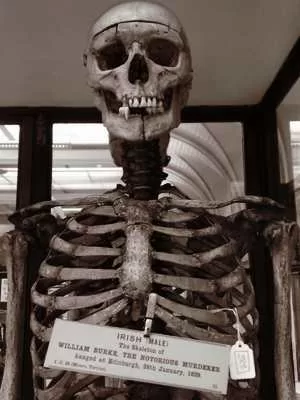

The following morning, Burke’s body was transferred to the Medical College for examination. Several prominent scientists studied it, and sculptor Mr. Joseph took a cast of Burke’s head for a bust. Descriptions of Burke noted his muscular build, with a thick neck and powerful legs, typical of a former navvy known for their strength.

Tickets were issued to authorized students, and at 1 p.m., Dr. Munro had already removed the top of Burke’s skull to expose his brain. He dipped his quill into Burke’s blood and wrote, “This is written with the blood of Wm Burke, who was hanged at Edinburgh.”

Chaos at the College

As students entered, many others were left outside, growing unruly. Fights broke out between police and students, leading to broken windows. The College Provost and his bailie tried to intervene but faced a hail of abuse. Eventually, Professor Christison promised that all students would be admitted in groups of fifty, calming the situation.

On January 30, 1829, the body of William Hare, Burke’s accomplice, was laid out for public viewing. Ironically, he too was a victim, now available for anatomical study. The top of his skull had been replaced, leaving only a faint scar.

Public Fascination

The spectacle was gruesome, satisfying the public’s appetite for horror. The doors opened at 10 a.m., and a steady stream of people filed through, with an estimated 25,000 viewing the executed man. Most were men, while a few women attempted to enter but were roughly handled and turned away.

After the public display, Burke’s body was quartered, salted, and stored in barrels. His skin was flayed, with some parts tanned. A former medical student even made a tobacco pouch from Burke’s neck skin, which still bore the mark of the rope.

Legacy of Infamy

Burke’s head measurements were used by phrenologists to support their theories, and a new verb, “to Burke,” emerged, meaning to suffocate someone. Over time, “burking” evolved to mean killing by suffocation. Interestingly, this term has no connection to the slang term “berk,” which is derived from rhyming slang.

The story of William Burke remains a chilling chapter in Edinburgh’s history. His execution and the subsequent fascination with his body highlight society’s complex relationship with crime, punishment, and the macabre. The legacy of Burke continues to intrigue and horrify, reminding us of the darker aspects of human nature.