The tale of William Bligh and the seventeen men from the HMS Bounty is one of extraordinary survival against overwhelming odds. After the infamous mutiny led by Fletcher Christian in April 1789, Bligh and his loyal crew found themselves crammed into a 23-foot launch, facing almost certain death.

With the waterline barely a handbreadth from the top of the boat, their situation was dire. They had scant provisions that were quickly spoiling, no charts or maps, and the weather was relentlessly against them.

Days turned into nights filled with frantic bailing just to keep the tiny vessel afloat. Heavy seas, towering waves, and constant rain battered the launch, leaving the men with no room to stretch out. Their muscles ached from the relentless effort, and the bone-numbing cold compounded their suffering. Despite Bligh’s best efforts to ration their meager supplies, starvation loomed ever closer.

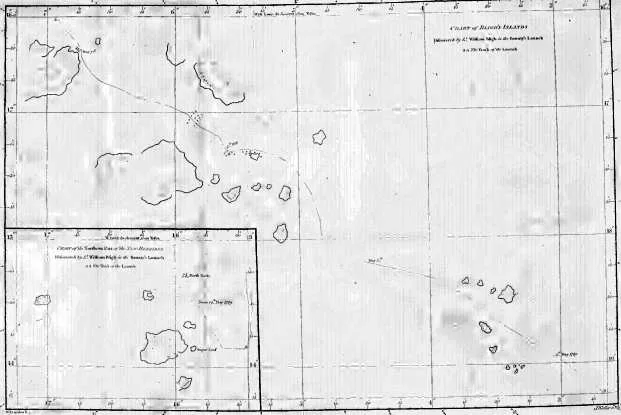

As they drifted through the Pacific, they passed by the Fiji Islands, too frightened to land for fear of being attacked again. They skirted the New Hebrides and crossed the treacherous Coral Sea. Remarkably, Bligh maintained a detailed log throughout their ordeal, documenting their misery and recording their approximate position, speed, and distance traveled. His meticulous notes provide a harrowing account of their journey.

On May 24, 1789, after fifteen grueling days at sea, the weather finally lightened, and the sun warmed their weary bodies. Bligh noted that the rain had likely saved their lives, providing them with precious drinking water. They began to see birds that indicated land was near, and they managed to catch a few, which they divided among the eighteen men. The sight of driftwood and the sound of breakers gave them hope, and Bligh, relying on his navigational skills and memory, believed they were nearing the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of New Holland (now Australia).

On May 29, they made landfall, where they were able to make a fire and prepare a broth from oysters and periwinkles. This moment was significant not just for the food but also for the much-needed rest they could finally enjoy without being cramped together. They took the opportunity to repair the launch as best they could, collected 60 gallons of fresh water, and gathered shellfish, planning to island-hop along the coast.

However, tensions began to rise among the men. Discontent simmered, particularly from Purcell, the carpenter, who had previously clashed with Bligh in Tahiti. In a moment of frustration, Bligh armed himself with a cutlass and threatened Purcell, who was described as “insolent to a high degree.” Bligh noted in his log that seven of the men were “not well disposed,” including Fryer, the master, and Lamb, the butcher, who had previously been flogged for losing his cleaver. Lamb, in a display of selfishness, caught and consumed several small birds in secret, further straining the group’s morale.

As the journey continued, illness began to take its toll. Several men required careful nursing while others foraged for food. Bligh navigated a course south of Papua, edging westward through the Torres Strait and into the Timor Sea. By June 8, he calculated they had rations sufficient for another nineteen days. Unfortunately, bad weather returned, bringing cold and the constant need to bail water, but they made steady progress. They even managed to catch a dolphin, which provided a much-needed meal.

On June 12, they sighted land, which Bligh believed to be Timor. Over the next couple of days, they made contact with local Malays, one of whom agreed to pilot the launch to Coupang. Bligh had a small flag made from signal flags, which he hoisted as they rowed into the harbor. Upon reaching shore, they were welcomed at the Governor’s mansion, where they were offered tea, bread, and butter. Bligh’s log captures the moment poignantly: “…their limbs full of sores and their bodies nothing but skin and bones, habited in rags, and at last let him conceive he sees the tears of joy and gratitude flowing o’er their cheeks at their benefactors.”

In just 48 days, Bligh and his men had sailed an astonishing 3,618 nautical miles in an open boat, losing only one man, John Norton, who was stoned to death on Tofua. Tragically, more men succumbed to the harsh conditions soon after reaching Timor. The botanist Nelson and the cook Hall died from the privations of their ordeal, while Peter Linkletter, William Elphinstone, and Robert Lamb likely perished from malaria contracted in the pestilential port of Batavia.

Eventually, in October 1789, Bligh boarded a Dutch East Indiaman, the Vlijt, which was granted permission to land him in British waters. He arrived on the Isle of Wight on March 13, 1790. By midnight, he was in Portsmouth, and the following morning, he took a post-chaise to London, arriving at the Admiralty just days after the 321st anniversary of the Bounty mutiny.

Bligh’s incredible journey is a testament to human resilience and leadership in the face of adversity. His ability to navigate treacherous waters and maintain morale among his men under such dire circumstances remains a remarkable chapter in maritime history. The legacy of the Bounty and its crew continues to captivate audiences, reminding us of the indomitable spirit of survival against all odds.