The story of the Pendle witches is one of the most infamous chapters in British history, intertwining themes of superstition, fear, and the harsh realities of early 17th-century justice.

The events surrounding the Pendle witch trials of 1612 are not only a reflection of the societal attitudes of the time but also a fascinating glimpse into the lives of those accused.

The man who played a pivotal role in the events leading up to these trials was Sir Thomas Kynvet, who famously arrested Guy Fawkes in the cellars beneath Parliament on November 5, 1605. Kynvet was also notable for being the first domestic resident of Number 10 Downing Street, which would later become the official residence of the British Prime Minister.

Interestingly, 10 Downing Street is actually a combination of three houses, including a mansion known as “the house at the back,” a townhouse, and a smaller cottage. The last resident of the cottage was humorously named Mr. Chicken.

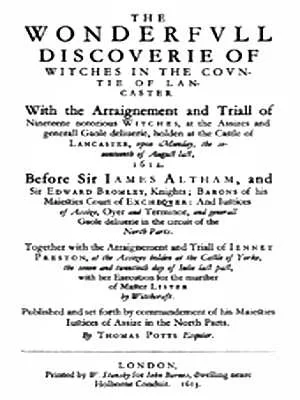

Among the Kynvet household was a young boy named Thomas Potts, who would later become an Associate Clerk on the Northern Circuit. In August 1612, Potts was in Lancaster when the circuit judges, Sir James Altham and Sir Edward Bromley, tasked him with documenting the proceedings of the witch trials. By November of that year, Potts had completed his account, which was published in 1613 under the title The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster. While the text is often criticized for its prolixity and repetitiveness, it remains a valuable historical document, providing insight into the trials, albeit not as a verbatim record.

Visiting Lancaster Castle as a child, I recall the chilling experience of being taken into the dungeons, where the tour guides would turn off the lights. The oppressive darkness and bone-numbing cold created an atmosphere of terror that was palpable. It is no wonder that Elizabeth Southerns, an elderly woman who was blind and crippled, died in custody before her trial. Her story, along with those of the other Pendle witches, has become a part of local folklore, with “Owd Mother Demdike” being a name that resonates even four hundred years later.

The Pendle witches were not the only individuals tried during the infamous sessions of August 18th and 19th, 1612. Other accused included Margaret Pearson, known as “The Witch of Padiham,” Isobel Roby of Windle, and seven so-called Salmesbury Witches. The trials began with Owd Mother Chattox, also known as Anne Whittle. Potts describes her as “a very old, withered, spent, and decrepit creature,” whose sight was nearly gone. Her confession had already sealed her fate, and she pleaded for mercy for herself and her daughter, who was yet to be tried.

Next was Elizabeth Device, the daughter of Demdike, who was described as “stunningly ugly” with a deformity that made her left eye appear lower than the right. Her previous confession had also sealed her fate. When she saw her nine-year-old daughter, Jennet, in the courtroom, she became agitated and had to be removed. Jennet, the only family member still free, was placed on a table and allowed to accuse her mother of witchcraft, claiming she had consorted with familiars and hosted a sabbat at Malkin Tower.

The trials continued with James Device, Elizabeth’s brother, who was in a weakened state after suffering in the dungeons. Potts noted that he was so insensible that he could neither speak nor stand. His mental state made him vulnerable to coercion, and he had already condemned himself. The evening of August 18th saw Anne Redferne tried for the murder of Robert Nutter, but she was found not guilty due to lack of evidence.

Ultimately, the jury returned guilty verdicts for Anne Whittle, Elizabeth Device, and James Device. The Pendle witch trials serve as a stark reminder of the dangers of superstition and the often brutal nature of justice in the early modern period. The legacy of these trials continues to resonate, not only in Lancashire but throughout the UK, as a cautionary tale of how fear can lead to the persecution of the innocent.

The Pendle witches remain a significant part of British folklore, their stories woven into the fabric of local history. As we reflect on their trials, we are reminded of the importance of justice, compassion, and the need to question the narratives that shape our understanding of the past.