The Defiant Legacy of Newton Knight: The Rebel Who Fought the Confederacy from Within

When Mississippi seceded from the Union in January 1861, the state’s political leaders led the charge in defending the institution of slavery. But not everyone in Mississippi was on board with the Confederate cause. Among those who resisted was Newton Knight, a poor farmer from Jones County who fought back against the Confederacy in one of the most unique and defiant acts of rebellion during the Civil War.

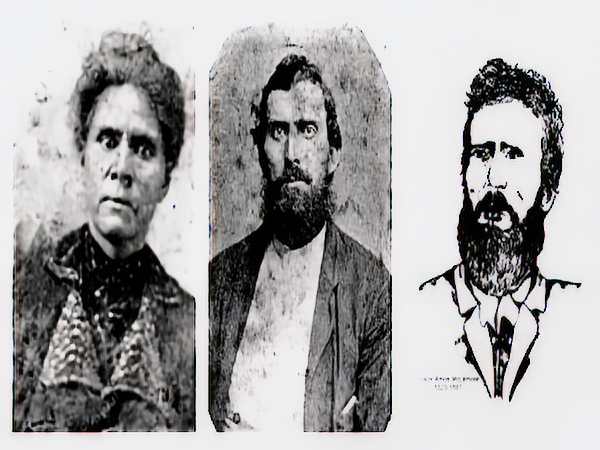

Newton Knight’s story is one of resistance, survival, and a fight for justice amid the chaos and destruction of the Civil War. Born in 1837 in Jones County, Mississippi, Knight grew up in a landscape dominated by towering pine forests and untamed wilderness. He married Serena Turner in 1858, and together they worked a modest homestead in Jasper County, growing corn and sweet potatoes and raising livestock. Knight was a hardworking man, known for his dedication to his family and his aversion to alcohol and foul language.

The Civil War and Mississippi’s Division

When Mississippi seceded from the Union, the state was swept up in war fever, but not all Mississippians were eager to fight. The people of Jones County, where Knight hailed from, were predominantly poor farmers who had no vested interest in preserving slavery. In fact, Jones County had the fewest number of slaves in the state. For Knight and his neighbors, the Confederate cause represented the interests of wealthy slave owners, not their own.

Many Southerners who opposed the war were labeled cowards and traitors, facing immense pressure to join the Confederate Army. For some, the penalty for refusing was death. Knight reluctantly enlisted in the fall of 1861, but his time in the army was brief. He returned home on furlough to care for his dying father, only to reenlist the following year as a private in Company F of the Seventh Battalion, Mississippi Infantry, alongside friends and neighbors.

But Knight’s commitment to the Confederate cause was weak at best. He had no desire to fight for a government that allowed the rich to sit out the war while the poor suffered. This sentiment was only strengthened by the passage of the infamous “Twenty-Negro Law,” which exempted planters who owned twenty or more slaves from military service. This law further fueled resentment among poor Southerners, who saw the war as one waged for the benefit of the elite.

Newton Knight’s Rebellion Against the Confederacy

In November 1862, after hearing that Confederate forces had taken his family’s horses, Knight deserted the army. He made the dangerous 200-mile journey back to Jones County, evading Confederate patrols along the way. Upon his return, he found a region devastated by war. The farms were in ruin, and the women left behind were struggling to feed their families. Confederate tax collectors exacerbated the situation, taking food, livestock, and supplies to support the war effort, leaving many families destitute.

Knight, now fueled by anger and a sense of injustice, refused to return to the army. He was arrested and imprisoned, but after enduring torture and the destruction of his property, he emerged even more defiant. Following the Confederate defeat at Vicksburg in July 1863, the number of deserters increased dramatically, and Knight began organizing a group of fellow deserters and Union sympathizers from Jones, Jasper, Covington, and Smith counties.

This group, known as the Knight Company, became a thorn in the side of the Confederacy. With Knight as their leader, the men launched a guerrilla war against Confederate forces, using the swamps and forests as hideouts. Their most notorious refuge, “Devil’s Den,” was located deep in the swamps, where the dense foliage provided cover from Confederate patrols. The Knight Company communicated using hollowed cattle horns, and sympathetic locals, both black and white, provided them with supplies and information.

Knight’s defiance made him a target of the Confederacy. In August 1863, Confederate authorities sent Major Amos McLemore to Jones County to round up deserters, but McLemore’s efforts ended tragically when he was shot and killed in the home of Amos Deason in Ellisville, Mississippi. Many believed Knight himself pulled the trigger, though he was never officially charged with the murder.

The Haunted Legacy of the Deason House

McLemore’s death added a ghostly layer to Knight’s story. As legend has it, after McLemore was shot, his blood seeped into the pine floors of the Deason house, leaving a stain that no amount of scrubbing could remove. To this day, it is said that the stain reappears whenever it rains or the wind howls. Locals believe the house is haunted by McLemore’s restless spirit, and on the anniversary of his murder, the front door is said to burst open without cause.

In 1991, the house was donated to the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), who restored it and opened it to the public. But even some DAR members confessed to being too frightened to stay in the house alone, day or night, due to the eerie atmosphere that lingers there.

The Knight Company’s Fate

The Confederate authorities were determined to stamp out the Knight Company, viewing their defiance as a humiliation. Many of Knight’s men were captured, tortured, or killed, with their bodies left hanging from trees as warnings to other deserters. Yet despite these efforts, Knight himself was never caught.

When the Civil War ended in 1865, the Federal government occupied Mississippi, and Knight was called upon to serve as a commissioner, tasked with distributing food to the impoverished people of Jones County. He also assisted in rescuing black children who were still being held in slavery in Smith County, a role that further cemented his legacy as a man who fought for justice and equality.

Newton Knight’s Final Years and Defiance in Death

After the war, Knight returned to his farm in Jasper County, where he lived out the rest of his days with Rachel, a former slave who had aided him during the war. Knight’s marriage to Rachel, following his separation from Serena, was a bold statement in defiance of the racial norms of the time. The couple had several children together, and when Knight died in 1890 at the age of 85, he ensured that his defiance would be carried to the grave.

Knight’s final request was to be buried next to Rachel, in defiance of Mississippi’s segregation laws. His gravestone, inscribed with the words “He Lived for Others,” stands as a testament to a man who fought for justice in the face of overwhelming adversity.