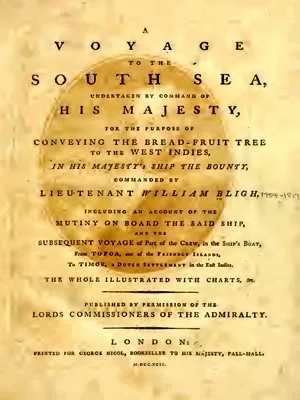

The story of the HMS Bounty and its infamous mutiny has captured the public’s imagination for over two centuries, blending historical fact with layers of myth and legend. At the heart of this tale is William Bligh, whose firsthand account, A Narrative of a Voyage to the South Sea (1792), provides an essential perspective on the events that unfolded.

Through Bligh’s eyes, we gain insight into the challenges and conflicts that led to one of history’s most famous mutinies, as well as the subsequent narratives that have shaped our understanding of this dramatic episode.

Bligh’s Account: A Man of His Time

William Bligh’s narrative offers a glimpse into the mind of a man deeply devoted to his mission. Having joined the Royal Navy at the tender age of seven, Bligh was a product of the era’s rigorous naval discipline. His commitment to duty and his professional demeanor are evident throughout his account. Bligh’s frustrations with his crew, particularly when faced with insubordination, are palpable, yet his concern for their well-being is also clear. He was not a man who relished punishment, but rather one who sought to maintain order with as little harshness as possible.

For instance, on March 10, 1788, Bligh reluctantly recorded his first instance of punishment: “Until this afternoon I had hopes I could have performed the Voyage without punishment to any One, but I found it necessary to punish Mathew Quintal with 2 dozen lashes for Insolence and Contempt.” By the standards of the time, two dozen lashes was a lenient sentence. Comparatively, Captain Edward Edwards of the Pandora ordered two men to be flogged 250 times each, and Captain Curtis of the Brunswick administered 278 lashes in just three-and-a-half weeks during the courts-martial that followed the mutiny.

Bligh’s preferred method of discipline was verbal rather than physical, earning him a reputation as a “nagger” among his crew. This characterization, however, does not fully capture the complexities of his leadership style. Bligh’s narrative suggests a leader who was firm but not cruel, determined to enforce discipline without resorting to unnecessary brutality.

The Retelling of the Mutiny: From History to Myth

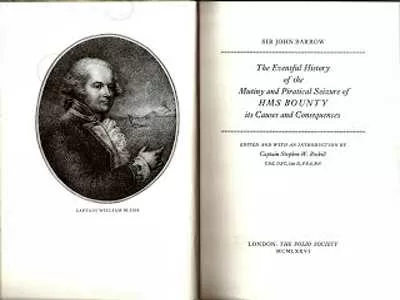

The story of the Bounty has been retold and reinterpreted in various forms, each adding new layers to the legend. Sir John Barrow’s The Eventful History of the Mutiny and Piratical Seizure of HMS Bounty (1831) is one of the earliest comprehensive accounts. Although Barrow used Bligh’s narrative as a primary source, his account also introduced additional details about the subsequent voyage of the Pandora and the settlement on Pitcairn Island. Barrow’s portrayal of Bligh was less than flattering, as he aimed to cast his friend, Thomas Heywood, in the best possible light.

Other works followed, each contributing to the evolving legend. The 1855 anonymous work Aleck focused on John Adams (also known as Alexander Smith), one of the mutineers who later became a pious leader on Pitcairn Island. The narrative highlighted the islanders’ adherence to the Bible and suggested that the mutiny might have been avoided had Bligh used more dignified language and maintained a more respectful demeanor toward his crew.

Literary interpretations of Bligh’s character continued to shift with John McGilchrist’s 1859 poem The Mutineers, which painted a harsh picture of Bligh as a feared and despised leader. Despite the poem’s dramatic portrayal, it acknowledged Bligh’s bravery and skill, adding to the complex image of a man both hated and respected by his crew.

Lady Diana Belcher’s 1870 book The Mutineers of the Bounty and their Descendants in Pitcairn and Norfolk Islands further complicated the narrative. As the stepdaughter of Thomas Heywood and the wife of Sir Edward Belcher, Diana had access to additional documents and sought to clear Heywood’s name, even as she recounted the Bounty’s history. Her work emphasized the Christian transformation of John Adams and the moral redemption of the islanders, contrasting sharply with Bligh’s image as an inflexible martinet.

The Cinematic Legacy: Fact Meets Fiction

The story of the Bounty has also been immortalized on screen, with varying degrees of historical accuracy. The first known cinematic version was the 1916 silent film The Mutiny of the Bounty, directed by Raymond Longford. Although this film is now lost, it was notable for its attempts to adhere to historical facts, a rare approach in the world of cinema.

In 1932, authors Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall published Mutiny on the Bounty, a novel that further cemented Bligh’s reputation as a cruel tyrant and Fletcher Christian as a wronged hero. The book’s success led to multiple film adaptations, each shaping public perception of the mutiny in different ways.

The 1935 Hollywood adaptation, starring Charles Laughton as Bligh and Clark Gable as Christian, took significant liberties with the story. Laughton’s portrayal of Bligh as a sadistic, power-hungry villain contrasted sharply with Gable’s dashing and noble Christian. The film’s dramatic embellishments, such as having Bligh order the flogging of a dead man, only served to further distort the historical record.

Marlon Brando’s 1962 portrayal of Christian in a lavish remake brought a new dimension to the character, although his interpretation of Bligh, played by Trevor Howard, leaned heavily on the trope of the cruel and vindictive officer. Despite its grand production, the film struggled with accuracy, favoring drama over historical fidelity.

In 1984, The Bounty, starring Mel Gibson as Christian and Anthony Hopkins as Bligh, offered a more nuanced take on the events. This film, directed by Roger Donaldson, remained closer to the historical facts, presenting both Bligh and Christian as complex individuals rather than one-dimensional characters. The screenplay by Robert Bolt allowed for a more balanced portrayal, reflecting the evolving understanding of the mutiny as a tragic conflict between duty and rebellion.

Conclusion

The mutiny on the Bounty is a story that has transcended its historical roots to become a legend, retold and reimagined countless times over the past two centuries. William Bligh’s own account remains a vital source for understanding the man behind the myth—a leader committed to his mission, yet flawed by the standards of both his time and ours.

The legacy of the Bounty continues to evolve, as each retelling, whether in literature or film, adds new dimensions to the characters and events that have fascinated generations. Whether viewed as a cautionary tale of tyranny and rebellion or a complex drama of human frailty and resilience, the story of the Bounty remains as compelling today as it was in the 18th century.