Gerardus Mercator, a 16th-century Flemish cartographer, is a name synonymous with mapmaking. His most famous creation, the Mercator projection, is a cornerstone of cartography, though often misunderstood.

Gerardus Mercator, born Geert de Kremer in 1512, was a Flemish cartographer whose innovations revolutionized mapmaking. His most significant contribution was the development of the Mercator projection, a method of representing the spherical Earth on a flat surface.

Mercator’s journey to cartographic fame began in his youth. Born into a modest family, he received a remarkable education thanks to the support of a wealthy uncle. He studied under renowned scholars, including the geographer Gemma Frisius, and honed his skills as an engraver and instrument maker.

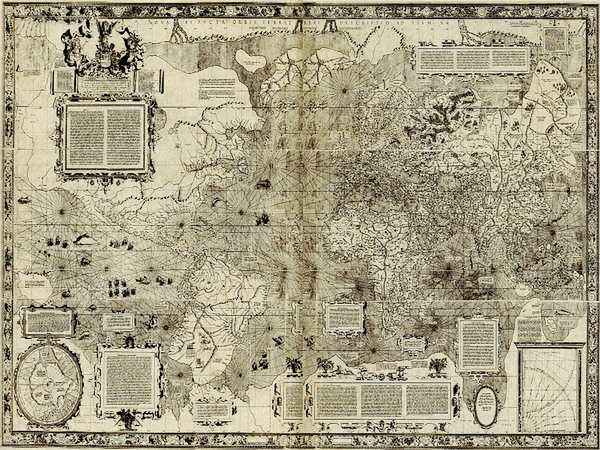

The Mercator projection, introduced in his 1569 world map, was a breakthrough. By representing the Earth as a cylinder, Mercator created a map where compass bearings appeared as straight lines, a boon for sailors navigating vast oceans. However, this accuracy came at a cost: the projection distorted the size of landmasses, particularly near the poles.

Despite its limitations, the Mercator projection became the standard for nautical charts for centuries. Its influence extends far beyond the realm of navigation, shaping our global perspective and influencing how we visualize the world.

Mercator’s legacy extends beyond his most famous creation. He produced numerous maps, globes, and scientific instruments, contributing significantly to the advancement of geography and cartography. His work laid the foundation for future mapmakers and explorers, shaping our understanding of the world and our place within it.

While Mercator’s map may not be entirely accurate in terms of landmass size, it remains a testament to human ingenuity and our relentless pursuit of knowledge. His contributions to cartography continue to inspire and inform, making him one of history’s most influential mapmakers.

Mercator’s breakthrough came in 1569 with the development of the Mercator projection. This cylindrical map projection represented a revolutionary approach to navigation. By maintaining consistent compass bearings, sailors could plot straight-line courses, simplifying their journeys. However, this accuracy came at a cost: the Mercator projection significantly distorts the size of landmasses, particularly near the poles. Greenland, for instance, appears far larger than its actual size.

Despite this limitation, the Mercator projection became the standard for nautical charts for centuries. Its ability to represent the world on a flat surface, while preserving directional accuracy, was invaluable to explorers and traders alike.

While Mercator’s map was a masterpiece of its time, it’s essential to remember the limitations of 16th-century cartography. The lack of accurate surveying techniques and limited global exploration meant that many parts of the world were still shrouded in mystery. The map’s details, particularly in regions like the Americas, were often based on hearsay, speculation, and a patchwork of available information.

In conclusion, the Mercator projection is a testament to human ingenuity and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. While it may not be a perfectly accurate representation of our planet, it remains an iconic and influential map that has shaped our understanding of the world for centuries.