Unveiling the Horrors of Unit 731

Key Points

- Unit 731,

- Japanese biological warfare,

- WWII atrocities,

- Ishii Shiro,

- Khabarovsk Trial,

- U.S. cover-up WWII,

- human experimentation WWII,

- Japanese war crimes,

- Emperor Hirohito WWII,

- Pingfang biological warfare,

- Manchuria WWII atrocities,

- biological weapons research WWII,

- Peter Williams Unit 731,

- Sheldon Harris Factories of Death,

- Japanese military WWII,

At the conclusion of World War I in 1918, the Japanese army’s medical bureau began exploring biological warfare, initially under Major Terunobu Hasebe, succeeded by Dr. Ito and a team of 40 scientists. However, the true genesis of Japan’s biological warfare effort emerged with the rise of Ishii Shiro. Graduating from Kyoto University’s medical department in 1920, Ishii immediately joined the army. By 1924, he returned to Kyoto University for graduate studies, married the president’s daughter, and earned his Ph.D. in 1927. Rejoining the army, he fervently promoted biological warfare.

Ishii Shiro’s Rise to Power

Ishii’s ascent in the Japanese military coincided with Japan’s growing militarism. His rise was bolstered by three critical elements:

- Western Influence: In 1928, Ishii was sent to Europe as a military attaché to study Western advancements in biological research. After two years abroad, he returned to Japan, was promoted to major, and dedicated himself to the research and production of biological weapons, advocating that modern wars could be won through science and technology. Ishii argued that biological weapons were economically advantageous for resource-poor Japan.

- Powerful Allies: Ishii garnered support from influential military figures, including Col. Tetsuzan Nagata, Col. Yoriniichi Suzuki, Col. Ryuiji Kajitsuka, and Col. Chikahiko Koizumi, known as the “father of Japanese chemical warfare.” Sadao Araki, the Minister of the Army and later Education Minister, also supported Ishii.

- Meningitis Breakthrough: After returning from Europe, Ishii designed a water filter that helped control a meningitis outbreak in Shikoku, boosting his reputation, particularly within the army. His lack of morality, sycophantic behavior towards superiors, and oppressive attitude towards subordinates furthered his military career.

Establishing the Center for Biological Research

Following Japan’s occupation of Manchuria after the Mukden Incident in 1931, Ishii moved the center for bacteriological research to northern Manchuria. This relocation allowed unlimited access to Chinese prisoners for human experimentation. In August 1932, Ishii led a group of scientists to Manchuria, deciding to make Harbin the research center and choosing a site 20 kilometers south for a human experimentation factory. The facility, known as Kamo Unit or Togo Unit, was established by the end of 1932, with a budget of 200,000 yen. Ishii was promoted to lieutenant colonel.

Formation of Unit 731 and Unit 100

In 1936, by order of Emperor Hirohito, two biological warfare units were established:

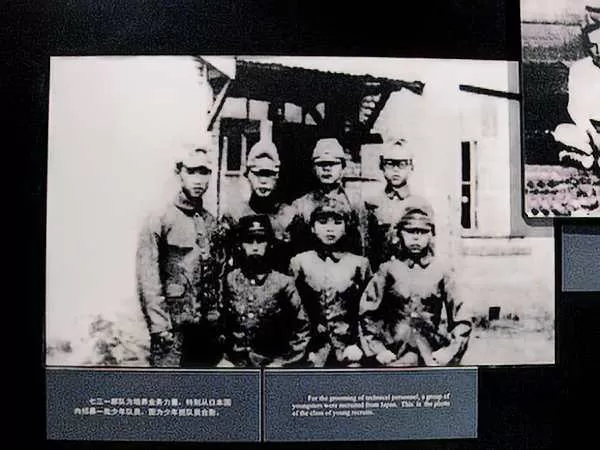

- Unit 731: Initially called the “Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kuantung Army,” it was relocated to Pingfang, 20 kilometers southwest of Harbin, in 1938. Occupying 32 square kilometers, Pingfang was designated a “no man’s land,” and Ishii, now a full colonel, commanded 3,000 Japanese personnel.

- Unit 100: Commanded by Yujiro Wakamatsu, later renamed Unit 100, was built near Changchun, focusing on veterinary disease prevention.

The Atrocities Unveiled

The joint work of Peter Williams and David Wallace, along with Professor Sheldon Harris’s “Factories of Death,” provides comprehensive accounts of Unit 731’s early history. They utilized sources such as the Fifty Year History of the Tokyo Army Medical College, Seiichi Morimura’s “The Devil’s Gluttony,” and Kei’ichi Tsuneishi’s works. These sources, along with testimonies from the Khabarovsk Trial, reveal the extent of the atrocities committed.

Unit 731 conducted horrific human experiments, including vivisections without anesthesia and testing biological weapons on live subjects. The 1933 budget of 200,000 yen and the establishment of the units by Emperor Hirohito are well-documented, underscoring the Japanese military’s commitment to biological warfare.

The Khabarovsk Trial and U.S. Involvement

In 1949, the Soviet Union held the Khabarovsk Trial, exposing the crimes of Japanese war criminals, including high-ranking members of Unit 731. Despite the revelations, the United States covered up these crimes in exchange for the data obtained from the experiments. This decision ignored international laws and human justice, allowing many perpetrators to escape prosecution.

Lasting Impact and Continued Denial

The atrocities of Unit 731 remain one of the darkest chapters in history. The denial by some members of the Japanese government exacerbates the pain of the victims and their descendants. Comprehensive works like those of Williams, Wallace, and Harris ensure that the horrors of Unit 731 are not forgotten, serving as a stark reminder of the potential for human cruelty and the importance of historical accountability.

Conclusion

Japan’s biological warfare efforts during World War II, spearheaded by Ishii Shiro and Unit 731, represent a grim legacy of scientific progress at the cost of human suffering. The subsequent cover-up by the United States only adds to the historical injustice. As we continue to uncover and acknowledge these atrocities, it is crucial to remember the victims and strive for a future where such inhumanity is never repeated.