This Disney-produced Jules Verne-esque fantasy-adventure film was a favourite of my childhood, and it stands up, at least for me, for several reasons. It retains many qualities I appreciated as both a lad and a grown aficionado of effective escapist cinema: a fast pace, a smart story, a vivid sense of mystery, and fascinatingly realised pre-CGI special effects that are both ropy and yet still gorgeous and interesting. It’s also one of the few real adventure yarns (adapted from Ian Cameron’s novel “The Lost Ones”) of ‘70s American cinema before Lucas and Spielberg gave the fantastic genres a total makeover, and the era of the blockbuster took true shape.

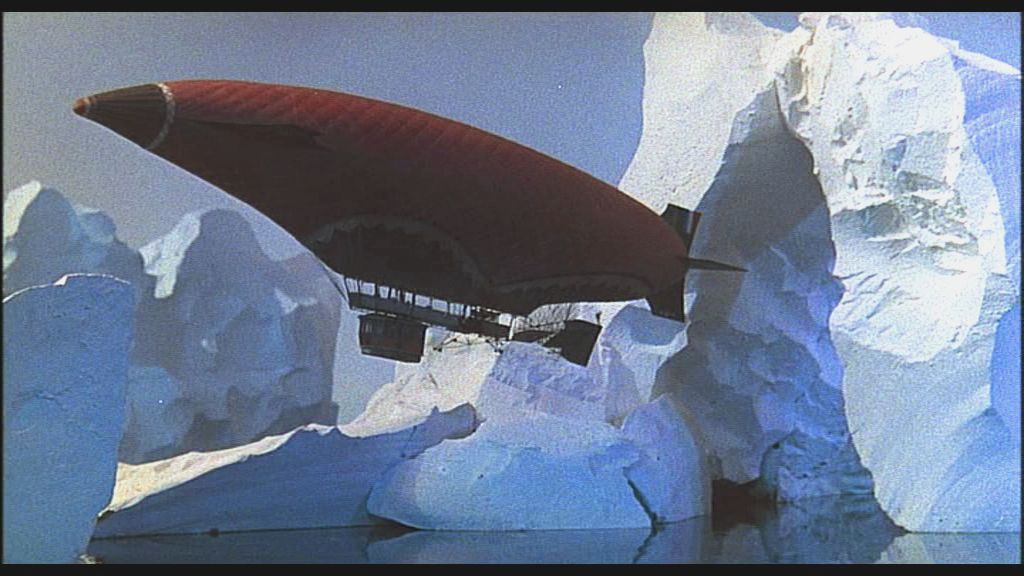

Early in the 20th century, high-powered, rather obnoxious English industrialist Sir Anthony Ross (Donald Sinden) is so desperate to find his son, Donald (David Gwilim), who ran away for a life of exploration and adventure, that he ropes in an expert in Nordic history, Professor Ivarsson (David Hartman), a French aviation pioneer, Captain Brieux (Jacques Marin) and his brand new airship the Hyperion, and Donald’s Eskimo guide and friend Oomiak (Mako) for his quest to locate a hidden island within the arctic pack-ice where, supposedly, whales go to die, and evil spirits dwell.

They soon enough locate the storm-tossed island, with the Hyperion bashed against soaring cliffs and the passengers dumped upon the rugged terrain, only to soon find the island hides a lush and fertile basin maintained by volcanic heat, and within which resides a long-lost colony of Vikings. Donald is living peacefully with them, but the arrival of other outsiders inspires the angry local high priest, the Godi (Gunnar Ohlund) to demand their death, believing they herald future invasion by barbarian hordes.

The plotting is all the more enjoyable for being grounded in the possible, considering the lengthy survival of some actual Viking colonies in the New World, and for taking some inspiration from the ill-fated Nobile expedition that was filmed in the altogether more grim The Red Tent (1969). This film however has a foot firmly planted in Disney’s penchant for nature and ethnographic documentaries, which perhaps explains the casting one-time Good Morning America host Hartman as Ivarsson, presumably so his plummy tones make his voiceover-like explications on various natural and historical phenomena sound appropriately learned – unfortunately he doesn’t so much act as constantly declare in a hearty but finally tiresome basso profondo. Also on offer is a buxom, mini-skirted Nordic lass Freya (Agneta Eckemyr) as Donald’s girlfriend, who looks like a reject from ABBA. She proves the party’s eventual rescuer from receiving a Viking funeral whilst still alive. And, yeah, and there’s the regulation cute dog.

It’s a touch disappointing for an adult viewer that, although it goes to such efforts to set up a detailed and potentially, vastly exploitable imaginative realm, it can’t wait then to leave it behind and turn into a chase movie. Hartman’s forced performance doesn’t help, but Sinden and Marins are funny as contrasting varieties of energetic arrogance. Most valuably and admirably, the carefully established and controlled atmosphere, which can be legitimately defined as proto-steampunk in using actual period technology for fantasy purposes, remains rich.

Director Robert Stephenson had been doing this sort of thing for forty years by this time, and he hardly wastes a frame in keeping his narrative on course. He had made his claim to prominence and emigrated to Hollywood on the back of his version of another, similar quest drama, 1937’s King’s Solomon’s Mines. This return to his roots helps explain why this is probably the least sticky of his many works as Disney’s premier director of live-action films (sorry, Mary Poppins fans). Best of all, the movie is driven along by a flavourful music score by Maurice Jarre, some of his finest, and most atypical, composition. Jarre’s work perhaps accounts much of the film’s nagging, nostalgic pull, but I have to admit the film also executes the adventure drama with a total lack of self-consciousness, and it’s not a shallow film. The lustrousness of the colour and the general technical excellence help make it more than cardboard adventuring, for there’s a genuine sense of anthropological curiosity to lend depth to the shenanigans. The usual social metaphors inherent in this type of tale – the heroes must contend with the whipped-up xenophobia of the Godi, whose power and sense of universal security is automatically threatened by outsiders – provide a metaphor for the exploitation of fear by political leaders, and are granted a new tincture by the context. The shock of meeting cultures, usually acted out between modern (white) men and real or metaphorical natives (a la Avatar), here occurs between new and old versions of Western Europe, and the gifts of the intervening centuries fail (Sir Anthony’s belief that his mastery of political and business spin can get them out of a jam proves ill-founded) to overcome more primal, but still readily recognisable, processes of social exclusion, scare-mongering, and manipulation. The islanders believe literally that the intrusion of the outside world brings the apocalypse. Which, indeed, it will, as they accurately sense, for their carefully preserved, actually remarkably organic and peaceful natural lifestyle will be doomed by discovery. Ivarsson predicts that in age of increasing mechanisation and industry, the corrosive results of that progress might demand that the island, and way of life retained there, might be a last lifeboat for humankind. There’s a truly haunting quality, then, to the conclusion in which Ivarsson agrees to remain behind as a hostage, and the rest set out across the ice to return to the greater world. Being as this was a mid-’70s film, both environmental and nuclear age concerns are obviously echoing here. It’s worth observing that screenwriter John Whedon was the grandfather of Joss Whedon, and so might have influenced that popular scribe’s fascination for the fantastic. The results anticipated the Indiana Jones films, and the well-evoked Norse settings and action scenes perhaps lingered long enough to have an influence on the minor renaissance of fantasy filmmaking in the 1980s.