The wave of action cinema Hollywood produced in the 1980s and early ‘90s finally retreated thanks to the convergence of decadently self-mocking flops like Hudson Hawk (1991) and The Last Action Hero (1993), the emergence of retro hipster irony in the Tarantino style not long after CGI split the streams with Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), and the emergence of an even flashier brand of director. Michael Bay’s The Rock (1996) marked the transition, quoting the institutional suspicion, unlikely fraternity, and situational intensity of ‘80s action, but realising it all in the most inflated, reality-distorting, fratboy-smug fashion possible. Whilst now nostalgically remembered for their air of unironic purity as engines of entertainment, something like the cine-cultural equivalent of a Detroit muscle car, the ‘80s action genre was at the time decried at the time just as broadly and violently as our contemporary CGI-fied spectacle blockbusters are, as heights of junk culture and deadening of the mass psyche. Shane Black is the fallen angel of ‘80s spec scripting, penner of the vastly overrated but still canonical ‘80s action film Lethal Weapon (1987) and co-star of another, Predator (1986), but ironically more associated with the demise of the style thanks to his overpaid involvement in bombs like The Last Boy Scout (1991) and Last Action Hero. Inviting Black to unite the eras and modes, and loan the personality of the old brand to the drenching spectacle of the new, was nonetheless inspired, but his achievement with Iron Man Three is a peculiar one. Black, who revived his career with the smart-arsed self-critique of Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2004), is a weirdly perfect creative simulacrum for Tony Stark, the self-reinvented wunderkind turned armour-plated superhero. Black’s rapid-fire dialogue and witty capacity to unite self-awareness with dramatic immediacy, promises what Iron Man 2 (2010) failed dismally to achieve, an action-comedy based as much in verbal fireworks as physical, and meshes well – almost too well – with Robert Downey Jr’s gift for machine gun-like patter.

One problem with the Iron Man branch of the Marvel franchise, which has dominated blockbuster cinema since the first entry in 2008, is that it’s the least imaginative of the Marvel realms, and Stark is essentially a good supporting character awkwardly installed as lead. The simplicity and clarity of the first Iron Man’s narrative proved unable to sustain much superstructure in the sequel, whilst, thanks in part to Hollywood spreading it far too thin with the godawful Sherlock Holmes films, Downey’s shtick grew quickly, irritatingly familiar. The Avengers (2012) seemed to prove it could maintain interest by forcing Stark to face off against figures equal in power but dichotomous in character. Iron Man 2 floundered terribly in its inability to find new levels in Stark’s character. Reverting to solo mode again was then fraught, but Black smartly knocks Stark right out of his comfort zone fairly early on and forces him, and the material, to maintain a more concerted, stoic pitch. Stark is challenged by the simultaneous appearance of two potential enemies who prove, of course, to be two heads of the same dizygotic beast, slicked-up nerd turned rival entrepreneur Aldrich Killian (Guy Pearce) and mysterious über-villain The Mandarin (Ben Kingsley), given to menacing broadcasts filled with pseudo-political messages, presaging mysterious detonations that do not seem to have been caused by any physical explosive. The roots for the current travails prove linked to Stark’s past as a dismissive libertine, as he once bullshitted Killian into going away whilst he slept with brilliant geneticist Maya Hansen (Rebecca Hall), who had found a way to regrow limbs on plants with an odd side-effect of making them explosive. Years later, having taken Hansen under his wing, Killian is now applying the technology to humans, including maimed veterans of recent American wars, giving a domestic blowback angle to the series’ hitherto corny and awkward basis in a geopolitical present-tense.

The early scenes of Iron Man Three are nearly as messy, mistimed, and diffuse as the worst of its predecessor, thanks to the insistence of a maintained style of quick-witted, faux-Hawksian repartee that just won’t come off. But once Black gets his story in motion he manages to bring some oddball humour, compulsion, and thrust to this work, if not quite managing to lift it out of the realm of common or garden franchise service. Black might have been expected to pay winking nods to his innate schooling in the ‘80s action style, but he tries to turn this into the whole show, an exercise in ebullient auteurist referencing and redemption, albeit one that just can’t quite grasp the essence of the model it’s honouring. Setting the film in the same mid-winter Yuletide season as many of his scripts, Black nods to the quandary of a tethered hero at the mercy of his enemies as in Lethal Weapon, the toppled cliff-top house and waterfront shootout of the 1989 sequel, trucking in familiar ‘80s genre heavies William Sadler and Miguel Ferrer as President and Vice-President, and even mockingly recasting the central hero and boy fan mystique of Last Action Hero as middle-act buddy comedy. The latter comes as Tony, forced to go on the lam after The Mandarin’s forces pound his beachfront house to rubble, flees to the sticks and hides in a shed, where he’s discovered by a boy, Harley (Ty Simpkins). Black sustains Tony and Harley’s interactions with a blend of mutual sarcasm and knowingness as well as genuine, old-fashioned empathy, so there’s no hint of irony to the payoff where the boy finds his abode filled with the trinkets Tony buys him. Nonetheless Tony and the kid’s shared sense of dark humour allows Tony to be at once paternal without losing his trademark acerbic trait, dissing the lad for pining for his father and telling him to suck it up.

Black’s most ingenious introduction and then despoilment of formula, meshing deftly with the insider satire of Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, sees Stark following in the footsteps of a hundred predecessors in the shoot-‘em-up genre in storming a Floridian villa. He takes out a small army of bodyguards, trying to locate the supervillain within. Except that The Mandarin turns out to be a vain, debauched licentious actor, happily ensconced with a pair of nubile tarts and enough intoxicating substances to wile away the hours in between fake propaganda broadcasts that both further and conceal Killian’s agenda. Black’s mischievousness here is twofold, disassembling the cliché of the supervillain with brash charm and hilarious pay-off. Also cheekily suggested in The Mandarin’s unmasking is Black’s own interpretation of “false flag” conspiracy theories: Killian’s plot is enabled by the Vice President, who has personal reasons for supporting Killian’s bastard science. This throws the film back more genuinely into the anti-authoritarian realm of much ‘80s genre cinema. But this twist essentially leaves the story stagnant: Tony’s battles with Killian never feel much more urgent than the average weekly episode of the old Bixby-Ferrigno The Incredible Hulk. Meanwhile Tony’s army buddy and fellow suited warrior James “Rhodey” Rhodes (Don Cheadle) is forcibly rebranded by dipshit government types as “The Iron Patriot”, festooned in red, white, and blue, in a propaganda exercise, but he’s reduced to taking handshakes from gleeful sweatshop workers when he crashes in to their factory in pursuit of another bogus Mandarin lead, one of the best examples of Black’s capacity to marry wit to story. It all feels like Black’s attempt to turn the staid, by-the-numbers story beats and expectations of the superhero genre on their head and transform the whole affair into Black’s malicious assault on the genre that helped displace his own.

Well, to a certain extent, anyway: try as he might Black can’t entirely disassemble the comic-book genre and recast it in his own image, as he can’t include the more adult edge of the old style, the quality that distinguished ‘80s action with its delight in the infernal, forbidden commodification of sex, drugs, and violence, in the context of the smoothly controlled, family branded Marvel stuff. But he gives it a sneaky good try. The action lacks the raw physicality and the superhero gadgetry still tends to take over the material and despoil the emphasis on heroic smarts and skill. As in J.J. Abrams’ first Star Trek (2009), the cliffhanger set-ups devolve anti-climactically when subject to sci-fi deus-ex-machina: when Tony is tied up at the mercy of his enemies, a la Riggs in Lethal Weapon, he’s saved not by peerless, ruthless desperation, but by his remote-controlled armour, a variation on a gimmick the films uses a couple of times too often. Black compensates by keeping Tony out of his suit as much as possible, to the extent that he and Rhodey venture into battle in the finale sans any protection other than guns and their wits, confirming their transformation into Riggs and Murtaugh. Another problem with the Iron Man series has been its pretty boilerplate action sensibility, and it’s in this aspect that Black proves weakest, offering only one strong action set-piece properly involving the suit, as Tony saves staffers from Air Force One in a free-fall plunge over the Florida coast, a sequence in the genuine spirit of the James Bond films it seems inspired by. The clash of impulses, between the expected franchise fan service, and Black’s devil-may-care approach to it, means that in many ways this entry is just as narratively messy as its predecessor: whilst he spurns distracting SHIELD and Avengers material, all dismissed with likeable contempt, Iron Man Three still feels overstuffed. Pepper and Maya, thrown in together after the destruction of the Stark house, disappear from the film seemingly forever before returning to the focus, and Maya’s part in the tale never quite takes on the importance it should.

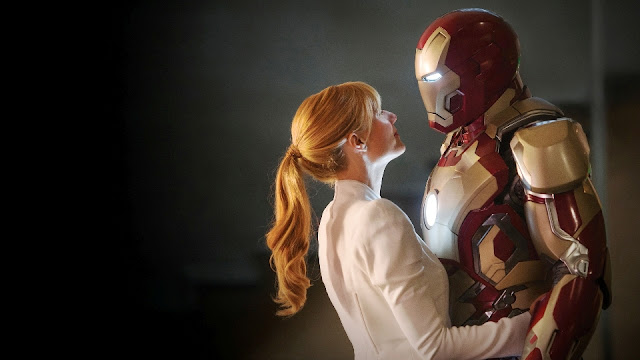

That said, Hall does well playing a role that’s well-conceived and hits unexpected notes, motivated less by anger against Tony than loyalty to Killian, and facing moral choices that are solved for her in an unexpectedly casual and brutal manner. Pearce makes his villainy so campy in its unabashed enthusiasm that he’s hugely entertaining when on screen, which sadly isn’t enough, whilst Kingsley’s joker-in-the-pack is essentially a throwaway delight. Paltrow gave her career a shot in the arm playing Pepper as a refreshingly grown-up and self-sufficient version of the usually duly passive superhero girlfriend, and whilst Black has trouble incorporating her cleanly into a narrative that depends of Tony’s detachment from his settled life, he does use her to provide a jolt of the genuinely personal urgency that gave life to the best ‘80s action, like Die Hard (1988), as Killian takes her captive and tortures her with Maya’s pyrotechnic formula. The finale, as Tony sees Pepper plunge to a fiery death, spurs one of the neatest I’m-gonna-kick-your-ass preludes to a death-match I’ve seen in a long time in an action flick. The punchline, that Pepper isn’t dead but instead has gained superpowers that allow her to smash Killian and save Tony, is equally neat. The final battle, complete with army of Iron Men remote-controlled by computerised Jeeves Jarvis (Paul Bettany), is staged on a dockside crane system that turns into a multi-levelled Escher-ish tangle of planes and stations: Black handles Tony and Rhodey’s place in the chaos well, but the rest is a rather confused whirlwind of standard-issue A/V crash and bang. The frustration of Iron Man Three is that it ultimately fails to cohere in the fashion of truly great action cinema, with that hard-driving singularity of focus that makes Predator or Die Hard so happily re-watchable, instead proving a big, entertaining but unwieldy machine, more ED-209 than Robocop, resting between genres and creative impulses rather than forcibly redefining anything. The very quality that makes the film amusing to fans of Black’s early work and the others from that milieu, partly conspires against the success of crossbreed. But it’s still more vigorously personal than Joss Whedon managed to make The Avengers, in spite of that film’s manifold pleasures, and a strong capper for the series, one which the executives hopefully won’t undercut by demanding another.