Armando Iannucci’s film adaptation-cum-sequel to the TV series The Thick Of It represents an honourable attempt to revive the big screen political satire, a form that was finally bludgeoned into clod-hopping irrelevance in Hollywood

Foster is therefore dispatched to Washington on an ill-defined mission of liaison, taking Toby with him, and soon finds himself being batted back forth between the pro- and anti-war forces within the State Department, the latter camp led by Karen Clark (Mimi Kennedy) and peacenik soldier Lt. Gen. George Miller (James Gandolfini). Karen’s desperate efforts to expose Barwick’s chicanery are dogged but outgunned, trying to wield a paper written by underling Liza Weld (Anna Chlumsky) that clearly establishes the cons far outweigh the pros in going to war, in resistance to the war’s onrush. Meanwhile it emerges that Tucker is the real emissary between the Prime Minister and Barwick, bringing over dubious but desperately required war intel, only to be frustrated to the outer reaches of obscenity-spouting by being palmed off onto twenty-something functionaries. Foster toys with making a stand and resigning, whilst Tucker finds himself momentarily caught with his pants down after Toby sees that Liza’s paper leaks to the British press, threatening a vote at the UN being rammed through by the pro-war forces.

In The Loop captures the minutiae and complex cross-currents of modern political life with unsentimental clarity. The contrast between the giddy thrill promised by Foster’s Washington escapade – although it finally proves to be little more than a series of hotel rooms, waiting rooms, and confused trailing – and the petty complaints and excruciating trivia in his home constituency, represented by a teetering wall that threatens to crush a garden shed belong to moustachioed crank Paul Michaelson (Steve Coogan), lays out the sharp contrast between the drug-like highs of imperial-scale politicking and humdrum, all-too-human-scale concerns. This elucidates not only how men like Foster, who have spent their lives pleasing people in order as a means to pleasing themselves, live and die by their lack of deep awareness, but also the disparities and lacks in whole political philosophies. Toby’s attraction to and short-lived tryst with Liza, whom he had a crush on when they were students together, in spite of his having a girlfriend, Suzy (Olivia Poulet), also a government functionary in Whitehall, personalises the irresistible siren call of the Americas to the drab, oppressively responsible Brits.

In The Loop is also a rare piece of British satire that’s competent in both sending up American characters and portraying them accurately and affectionately. Miller, on the surface formidable and one of the few people in the film capable of handing Tucker his arse on a plate, has anxieties and inadequacies which are empathetically revealed, as he displays his rage at getting the run-around from Barwick, and contends with his love-hate relationship with the droll, principled Karen. Their like-minded attitude to the war as ill-planned and dangerous is coloured by a long-ago sexual escapade, and by their final divergence of loyalties, his as a soldier and hers as a public servant who actually wishes to serve the public. In The Loop also directs a coolly accurate eye on a haute macho pre-eminence where the likes of Tucker and Barwick feel entirely justified in brushing aside Judy and Karen – Tucker constantly assumes the former to be a disloyal incompetent. That McKee especially retains her ever-sturdy poise is admirable under the circumstances.

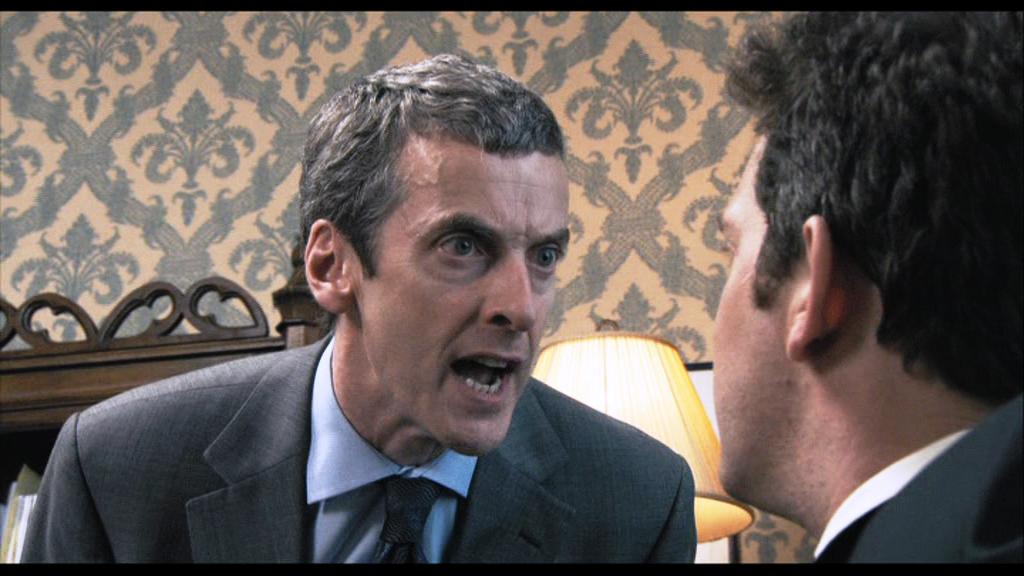

Tucker’s bruising encounters with Miller and Barwick momentarily rattle that human cesspit’s confidence, who experiences crisis in contending with people who aren’t discombobulated by his aggression, because their sense of power and how to wield it makes his own actual fiefdom look humiliatingly petty. The film’s single moment of truly affecting human vulnerability is one in which Tucker, having been humiliated by Barwick and knowing his own position can’t withstand even a single major blow, stews in momentary anguish. Therefore he becomes, ironically, and very temporarily, something of an anti-hero in trying to work up an effective comeback to Barwick’s arrogance. Barwick’s weird mixture of contempt for anyone who’s not on his programme and war-hungry prerogative, and timidity about swearing properly and his middle-management way of fobbing people off, makes him even less likeable than Tucker.

In The Loop does what it does exceptionally well, in the constant stream of wittily profane dialogue – which proves that’s not a contradiction in terms – matched to performances of wall-to-wall excellence, if only in service to essentially one-dimensional characters. If it feels a bit underwhelming in total, especially considering the praise heaped upon it chiefly for filling a dearth of relevant commentary that isn’t leaden and preachy, it’s partly because the concept hasn’t moved that far from a TV sitcom. The episodic structure of the story bears that out, and Iannucci’s filmmaking is for the most part basic, full of stock-standard faux-documentary quick zooms and hand-held shots, if rendered in exceptionally pretty terms by Jamie Cairney’s cinematography. In The Loop’s narrow focus hews close to the formula of much current British television comedy, full of awkwardness, disparagement, piss-weak neophytes who can’t keep their dicks in the pants, authority figures who have no authority, and women who go through break-ups and betrayals with listless, by-rote outrage. British political satire has sunk a long way in terms of conceptual boldness and originality from the likes of The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer (1971) and O Lucky Man! (1972). That Tucker takes over the material is inevitable because he’s the only person who isn’t, in some fashion, pathetic, and he starts to seem less a portrait of gross power politics than a remorseless instrument of sadomasochistic punishment of the lesser mortals who have inherited the hallowed but hollowed-out bastions of the British Empire.

The narrative’s ironies, which see the few people who try to take a stand against the war cold-shouldered, pushed into irrelevance, or even destroyed, to enable this dubious adventuring, are dulled somewhat, in large part because the filmmakers take such obvious, giddy-making relish in the grotesque behaviour of Tucker and his (even worse) Scots compatriot in bureaucratic head-kicking, Jamie MacDonald (Paul Higgins). MacDonald overtly terrorises Suzy and her officemate Michael Rodgers (James Smith) by kicking a fax machine to pieces when he discovers the leaked report came from their office, in contrast to the smarmy inefficaciousness of Foster and the younger characters like Toby whose moral compasses are fatally compromised by their wayward impulses. The whole thing’s divorced from any real sense of the horror that’s about to be unleashed, and starts to take on a smell less redolent of a devastating critique of closed-circuit, on-message politics, than it does of liberal self-pity. Considering the very real highs of surrealism and lows of tragedy that defined the real process of driving towards the Iraq