In January 1947, a routine task turned into one of the most significant archaeological events of the 20th century. Juma, a Bedouin shepherd, noticed some of his goats straying too close to the perilous cliffs overlooking the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea. Concerned for their safety, Juma decided to climb the cliff face himself to retrieve them. Little did he know, this seemingly mundane task would lead to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls—the greatest manuscript treasure ever unearthed.

During his climb, Juma came across two small openings in the cliffside caves. Curious, he threw a rock into one of the openings, hearing an unexpected crack that hinted at hidden contents. Intrigued by the possibility of treasure, he summoned his cousins, Khalil and Muhammed, to investigate. As daylight faded, they resolved to return the next day to explore further, imagining the potential riches that could be hidden within the caves.

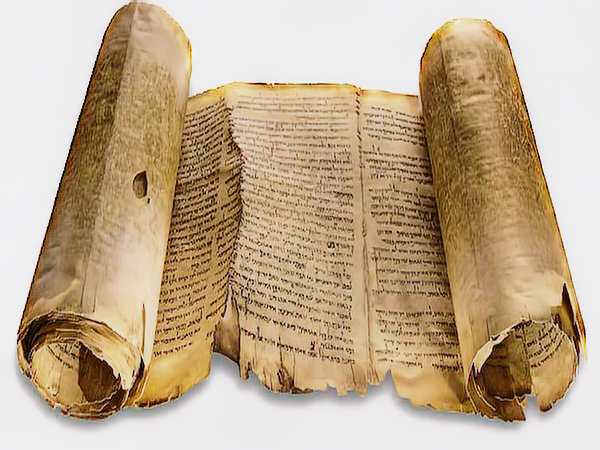

The following morning, Muhammed, eager to discover what lay within, ventured into the cave alone. The cave floor was littered with debris, including broken pottery. Against the backdrop of the cave’s dark walls stood several narrow jars, some still covered with their bowl-shaped lids. Muhammed examined each jar but found no gold or precious artifacts—only bundles wrapped in old cloth. Disheartened, he returned to his cousins with the disappointing news that no treasure had been found.

However, the discovery of these scrolls was anything but ordinary. What Muhammed and his cousins had stumbled upon were the first seven manuscripts of the Dead Sea Scrolls. These texts were over a thousand years older than the previously known Hebrew Bible manuscripts and included writings from more than a century before the birth of Jesus. The scrolls would soon captivate the archaeological world and present a formidable challenge to scholars and translators.

The journey of these ancient texts from the remote cave to the hands of international scholars is a tale filled with intrigue. After being initially stored in a Bedouin tent, the scrolls were sold to two Arab antiquities dealers in Bethlehem. Four of these scrolls were purchased for a modest sum by Athanasius Samuel, a Syrian Orthodox Metropolitan at St. Mark’s Monastery in Jerusalem. It was through the efforts of scholars at the American School of Oriental Research that their historical significance began to be understood. John Trever meticulously photographed the scrolls, and the renowned archaeologist William F. Albright confirmed their dating to between 200 BC and AD 200.

Meanwhile, three additional scrolls found by the Bedouin boys were sold to E. L. Sukenik, an archaeologist at Hebrew University and father of Yigal Yadin, who would later become a notable figure in Israeli archaeology. The tensions of the final days of the British Mandate in Palestine added a layer of urgency and danger to the examination of these artifacts.

The scrolls eventually came together at Hebrew University under rather remarkable circumstances. Metropolitan Samuel, after struggling to find a buyer for the scrolls, placed an ad in the Wall Street Journal. By chance, Yigal Yadin, who was lecturing in New York at the time, saw the ad. Through intermediaries, Yadin was able to acquire the scrolls for approximately $250,000. In February 1955, the Prime Minister of Israel announced the purchase of the scrolls, which were then housed in a special museum at Hebrew University, known as the Shrine of the Book, where they remain on display today.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls sparked intense archaeological interest and led to further explorations. An official expedition launched in 1949 resulted in the discovery of ten additional caves in the surrounding area, each containing scrolls and fragments. The focus then shifted to the nearby ruins of Khirbet Qumran, initially thought to be a Roman fortress but later identified as the site of a Jewish community that thrived between 125 BC and AD 68. This community, believed to be the authors of the scrolls, had hidden their texts in the caves as the Roman army approached during the Jewish Revolt of AD 66-70.

Excavations at Qumran revealed the remnants of a structured community, including storehouses, aqueducts, ritual baths, and an assembly hall. Among the most intriguing finds was a scriptorium with ink wells and benches, where it is thought that many of the scrolls were copied.

The Dead Sea Scrolls include a diverse array of texts. The original seven scrolls from Cave One featured:

- A well-preserved copy of the Book of Isaiah, the oldest known Old Testament manuscript

- A fragmentary scroll of Isaiah

- A commentary on the Book of Habakkuk

- The “Manual of Discipline” or “Community Rule,” detailing the practices of the Qumran community

- The “Thanksgiving Hymns,” a collection of devotional psalms

- An Aramaic paraphrase of the Book of Genesis

- The “Rule of War,” outlining an eschatological battle between the “Sons of Light” and the “Sons of Darkness”

In total, over six hundred scrolls and thousands of fragments have been discovered, including every Biblical book except Esther and various non-Biblical texts. Among these was a copper scroll listing treasures hidden across Judea—none of which have been found—and the “Temple Scroll,” detailing elaborate temple rituals.

The scrolls provide valuable insights into the Jewish sect that produced them. They reflect a communal life devoted to strict religious observance and anticipation of an imminent divine judgment. The community expected the arrival of three messiahs—a prophet, a priest, and a king—which contrasts with the New Testament portrayal of Jesus, who embodies all three roles.

The Dead Sea Scrolls have profoundly impacted our understanding of the Hebrew Scriptures and the religious landscape of the time. They reveal a meticulous effort to preserve sacred texts and offer a fascinating glimpse into the beliefs and expectations of their authors.