The story of New Zealand’s giant moa (Dinornis giganteus) unravels a tale of colossal flightless birds that once dominated the island’s landscape. Known for their impressive size and significant role in the island’s ecosystem, these prehistoric giants have fascinated scientists and historians alike. Let’s explore the enigmatic world of the moa, from its towering stature to its abrupt extinction.

Majestic Giants of the Past

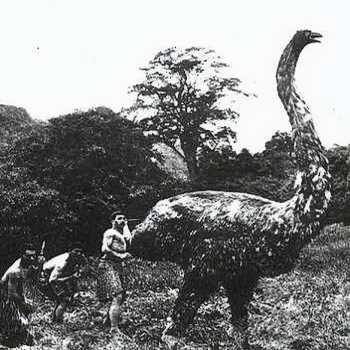

The giant moa, a member of the ratite family, was one of several species of moa that roamed New Zealand. These flightless birds were remarkable not only for their height but also for their sheer size. Standing at up to 13 feet (4 meters) tall, moas were twice the height of an average man and weighed as much as 275 kg—three times the weight of a large man. Their height, combined with their robust build, made them formidable creatures, although they were more lightly constructed compared to the elephant bird.

Interestingly, the moa’s neck likely projected forward, similar to a kiwi, rather than upward as often depicted in illustrations. This unique posture highlights the differences in their anatomy and behavior compared to other large flightless birds.

Enigmatic Eggs and Size Differences

The moa’s eggs were equally impressive, measuring about 10 inches (24 cm) long and 7 inches (18 cm) wide. Females of the species were notably larger and heavier than males, with females weighing nearly three times as much. This significant size difference led scientists to initially mistake males and females for separate species. However, modern research has clarified that these size variations are due to sexual dimorphism rather than distinct species.

The Moa’s Habitat and Extinction

New Zealand’s isolation from other land masses made it a unique habitat for the moa. Unlike Madagascar, which had its own set of peculiarities, New Zealand had no land mammals except bats. The giant moas thrived in this environment, living in semi-tropical forests and grasslands. They occupied ecological niches similar to large herbivores found elsewhere in the world.

The arrival of the Polynesians, ancestors of the Māori, around the 10th century marked the beginning of significant changes for the moa population. The Māori, having no prior experience with such large animals, quickly became skilled at hunting them. This intense hunting pressure, combined with the absence of natural predators, led to a rapid decline in the moa population.

By the time Europeans first encountered New Zealand in 1770, the giant moas had already been driven to extinction, with the official extinction date recorded as 1773. It wasn’t until the 1830s that European scientists confirmed the moa’s existence through fossil discoveries.

Discovering the Moa

The moa’s discovery was a gradual process. In 1838, Englishman John Rule brought a fragment of a large leg bone from New Zealand to London, which was examined by paleontologist Richard Owen. Despite initial skepticism and dismissal of the find as a hoax, further discoveries and analyses eventually convinced the scientific community of the moa’s existence.

In 1843, Reverend William Williams, a geologist and missionary, sent additional moa bones to England. Williams had also recorded a sighting of a massive bird by English whalers in 1842, describing it as standing 14 to 16 feet tall. This account further intrigued scientists and added to the growing body of evidence.

The 1850s saw continued reports of moa sightings and even claims from sealers on the South Island who purportedly ate moa meat. Detailed accounts from Māori elders provided insights into the moa’s appearance, behavior, and ecological role, painting a vivid picture of these once-mighty birds.

Scientific Insights and Ongoing Mysteries

The moa family, classified under Dinornithidae, was diverse, encompassing several species with varying sizes and characteristics. Among them were the long-legged Dinornis, short-legged Pachyornis, and the smaller Emeus, each exhibiting distinct anatomical features. Notably, the moas lacked humeri (upper arm bones), indicating a complete absence of wings.

Other moa families included the pygmy moas, which were turkey-sized and may have survived into the early 20th century. Reports suggest that some pygmy moas possibly lived on into the 1900s in the wilderness of Fiordland.

The extinction of the moas was a direct result of overhunting by the Māori, followed by the arrival of European settlers. The massive birds, which had evolved in isolation without predators, were ill-equipped to handle the new threats posed by human activity.

Legacy and Preservation

Today, moa bones and fossils provide valuable insights into these ancient giants. Museums in New Zealand and Europe house exhibits featuring moa skeletons, models, and reconstructions based on preserved feathers and oral histories. Despite their extinction, the legacy of the moa continues to captivate the imagination of scientists and the public alike.

In summary, the giant moa represents a fascinating chapter in New Zealand’s natural history. Its enormous size, unique anatomical features, and the dramatic impact of human activity on its extinction offer a poignant reminder of how isolated ecosystems can be profoundly affected by new forces. As we continue to study and reflect on the moa, its story serves as a testament to the intricate balance of nature and the far-reaching consequences of human intervention.