Exploring the Rich History of Culinary Literature

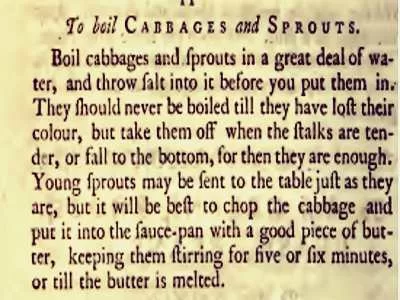

Abraham Lincoln once remarked that “17% of what you read on the Internet may well be inaccurate.” This sentiment rings true in the world of culinary literature, where historical inaccuracies can easily slip through the cracks. For instance, I previously stated that the first recipe for Brussels sprouts appeared in Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery (1845).

However, I recently discovered that the earliest reference can actually be found in Cookery Reformed: or, The Lady’s Assistant, published in 1755—nearly ninety years earlier. I apologize for this oversight and appreciate the opportunity to clarify.

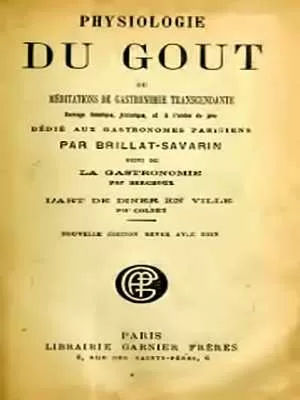

Culinary literature encompasses a wide range of topics, from cooking techniques to the philosophy of eating. One of the earliest and most influential works in this genre is Jean Brillat-Savarin’s Physiologie du goût (The Physiology of Taste), published in 1825. This substantial tome, nearly five hundred pages long, invites readers to savor its contents much like a fine meal.

Brillat-Savarin, an epicure in the truest sense, believed that “animals feed, man eats; wise men alone know how to eat.” His philosophy echoes the teachings of the Greek philosopher Epicurus, who posited that the ultimate aim of life is pleasure, or more accurately, the absence of pain.

However, the common portrayal of Epicureanism as mere hedonism overlooks the nuanced understanding of balance that both Epicurus and Brillat-Savarin advocated. “Too much is as wrong as too little,” Brillat-Savarin wrote, emphasizing the importance of moderation. He encourages readers to approach his work in measured portions, allowing time to digest both the food and the ideas presented within.

Brillat-Savarin’s writing is rich with anecdotes, reflections, and digressions that engage the reader’s senses. He tantalizes with phrases like, “Dessert without cheese is like a pretty girl with only one eye,” showcasing his belief that French cuisine is unparalleled. Before the seventeenth century, French cooking was similar to that of other European nations, but a transformation began with chefs like François Pierre de la Varenne and Marie-Antoine Carême. They shifted the focus from heavy spices to fresh herbs, vegetables, and simpler sauces.

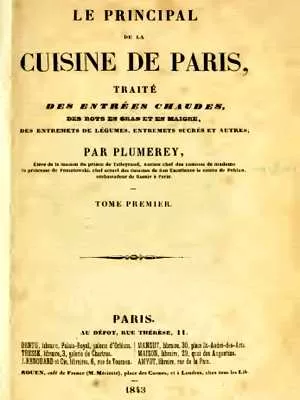

Carême, often referred to as the “King of Chefs” and the “Chef of Kings,” revolutionized French cuisine by introducing the concept of “mother sauces” (Béchamel, Hollandaise, Velouté, Tomate, and Espagnole). These foundational sauces could be adapted to create a variety of secondary sauces, allowing for greater culinary creativity. He also pioneered the service à la Russe, which involved serving dishes separately in the order of the menu, as opposed to the traditional service à la Française, where all dishes were served simultaneously.

Following Carême’s legacy, Auguste Escoffier further refined French cuisine with his seminal work, Le Guide Culinaire (1905), which set the standards for haute cuisine. This book became the cornerstone of classical French cooking, influencing high-end restaurants and hotels worldwide throughout the 20th century. Aspiring chefs today must familiarize themselves with French techniques, methods, and ingredients, as they remain essential in the culinary arts.

The dominance of French cuisine has sometimes led to an inverted snobbery, particularly among those who struggle with the language. Sentiments like, “Do you think it easy to sell Irish Stew for 75 cents when you can sell Navarin d’Agneau à l’Irlandaise for a dollar?” reflect a misunderstanding of culinary value. A little effort in understanding recipes can go a long way in navigating menus and appreciating the art of cooking.

In Victorian times, even pocket guides were available to help the average person navigate the culinary landscape. Today, as we continue to explore the rich history of culinary literature, we find that the lessons of the past remain relevant. Whether through the philosophical musings of Brillat-Savarin or the technical mastery of Escoffier, the journey of food and its appreciation is a timeless endeavor.