Tim Bobbin, known for his eccentricity, left a complicated legacy. His unique traits seemed to pass down to his sons, leading to a tragic fate for each of them. This article explores the lives of Tim Bobbin’s sons, their struggles, and the madness that ensued.

John Collier: The Eldest Son

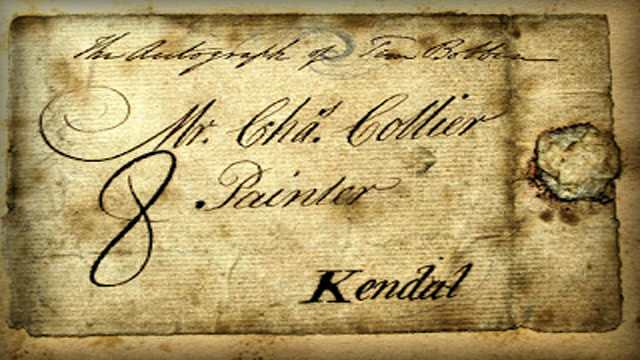

John Collier Jr. was born in February 1744 in Milnrow. His father, Tim Bobbin, educated him as a painter. At just twelve, John became an apprentice to a herald painter named Mr. Bowcock in Chester. After completing his apprenticeship, he moved to York and then settled in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1766. There, he worked as a coach painter and heraldic artist.

John found success in Newcastle, earning a profit of £60 in his first year. He invited his younger brother, Thomas, to work for him. However, their relationship soured quickly. John complained to their father about Thomas being lazy and conceited. In August 1767, Thomas left, and John replaced him with their brother Charles.

Struggles with Family and Marriage

John’s dissatisfaction continued. He often criticized Charles, which may have stemmed from his own stubbornness. In January 1768, John married Betty Ranken, the youngest daughter of a wealthy businessman. Betty brought a dowry of £400, which John used to expand his home and studio. Unfortunately, the extension encroached on land owned by Mr. Drummond, leading to a legal battle that resulted in the demolition of the addition.

John’s mood worsened after Betty’s death in 1777. Later that year, he married Betty Howard, who was much younger. Their marriage raised questions about its legality, especially since she used a false name. John’s mental state deteriorated further. He accused Betty of putting iron filings in his clothes and even assaulted her with a poker.

A Descent into Madness

In 1778, John published a book titled An Alphabet for the Grown-up Grammarians of Great Britain. In it, he humorously described the alphabet, calling it a mix of vowels, mongrels, and “one devil knows what,” referring to the letter Q. His erratic behavior escalated when he threatened his printer, Mr. Slack, and attempted to shoot him.

John was committed to an asylum, where his brother Thomas found him chained to a bed. Thomas struggled to secure his brother’s release, fearing John’s threats against local magistrates. In January 1779, Thomas finally succeeded, and they moved to Penrith. There, John racked up bills for printing and parts for an electrical machine, convinced he could transfer thoughts between people using electricity.

Life in Milnrow

Returning to Milnrow, John adopted bizarre habits. He wore an iron hood he made himself and turned his clothes inside out. Eventually, he settled on wearing sackcloth. He owned cottages in Milnrow and, feeling wronged by his tenants, tried to evict them. When the legal process took too long, he sealed the cottages, stuffing the chimneys with grass and hay. When the tenants lit their fires, smoke filled the cottages, and John refused to open the doors until they agreed to leave.

John Collier died in 1809 at his nephew James Clegg’s home.

Thomas Collier: The Troubled Brother

Thomas, John’s younger brother, faced his own challenges. One day, while the Newcastle church steeple was being repaired, Thomas climbed the spire but panicked at the top. A steeplejack had to rescue him, beating him with a rope-end in the process. Thomas became involved in politics and was nearly killed during a protest. He published a book of political poetry, which caught the attention of the magistrates, leading to his imprisonment and the burning of his book.

Later in life, Thomas developed an interest in astrology, calling himself a “conjurer and professor of mighty magic.” However, his business failed, and he returned to Milnrow, where he died in 1825.

Charles Collier: The Youngest Brother

Charles, the youngest brother, was also a painter. He initially found success and married a widow who provided a yearly income of £100. With this money, he bought Tim Bobbin’s cottage for their parents. However, when his wife died, Charles returned to Milnrow. He worked as a portrait painter and flannel merchant, but his love for hunting and field sports led to the failure of his business.

Charles became an itinerant portrait painter, traveling extensively. In just three months in 1802, he visited cities like Oxford, London, and Brighton. He was obsessed with watching military reviews, even walking from Rochdale to Dover for one. In 1812, he camped out to be among the first to witness a review at Kersal Moor in Manchester. Sadly, he died in poverty later that year.

Conclusion

The story of Tim Bobbin’s sons is a tragic tale of eccentricity turning into madness. John, Thomas, and Charles each faced their own struggles, shaped by their father’s legacy. Their lives remind us of the fine line between creativity and madness, and the impact of family dynamics on mental health. The Collier brothers’ stories serve as a poignant reminder of the complexities of human nature and the challenges that can arise from inherited traits.