Jacques Audiard, a screenwriter since the 1970s who turned to directing in the ‘90s, broke through to international attention with his sly, vibrant 2001 thriller Read My Lips. Since then Audiard has been both a popular and admired filmmaker at the forefront of current French cinema, but also something of an outlier in the blended impulses of his works. He’s an unabashed lover of storytelling, delighting in tales of people beating the odds and rising to challenges of grim fate. He’s a dramatist belonging to a credo of French drama stretching back to the heightened effects and melodrama of Zola and De Maupassant, illustrating the intensity of existence through whatever image or motif he sees fit. He’s a fan of ‘70s New Wave Hollywood, less interested in pondering political and cinematic semantics than in illustrating daily dramas as vividly as possible, and one with the chutzpah to remake James Toback’s Fingers (1977) as The Beat My Heart Skipped (2005). He’s a contemporary realist, exploring the down and dirty side of life in contemporary France with an exacting sense of milieu and character as defined by survival in those zones, grazing territory long staked out by the likes of Ken Loach and the Dardennes Brothers. Dheepan, his latest, captured last year’s Cannes Palme d’Or but has had a slow and relatively half-hearted distribution and reception, in part because of Audiard’s straddling way: it’s not exactly a standard vigilante thriller nor entirely an earnest, entirely down-to-earth tale of social issue angst.

It’s not hard to see, nonetheless, why it captured the top Cannes prize, as Dheepan offers intersecting concerns of the moment – the place of refugees in today’s Europe, still dealing with harsh blows to its confident prosperity, and the consequences of a sink-or-swim attitude towards people on the bottom rung of society – blended with less bluntly topical notions, as Audiard burrows into the nature of personal identity and its relationship with the wider state of civic cohesion and order, the question of whether simply living morally for one’s self is enough in an iniquitous and dangerous zone of existence. He utilises neorealist conventions in casting leads who had never acted before, with star Jesuthasan Antonythasan playing a role close to his own life experience. Audiard kicks off his film with a display of seemingly casual and jumpy, actually carefully controlled storytelling method as he depicts his protagonist, Sivadhasan (Antonythasan), a Tamil revolutionary soldier who’s survived the carnage of the movement’s defeat, burning his comrades on funeral pyres and adding his own uniform to the flames. In a refugee camp, the army gives out new identities to those who want to emigrate, perhaps to get rid of the last of defeated troublemakers. Sivadhasan is assigned the identity of a dead man named Dheepan, and he has to rustle up two people willing to fill in for Dheepan’s wife and child, also dead. He’s soon matched with “Yalini” (Kalieaswari Srinivasan), who then combs the camp to find a potential daughter, eventually finding one (Claudine Vinasithamby) willing to become “Illayaal.” Although Yalini hopes to eventually move on to England where her cousin lives, Dheepan decides to make a home in France, where he has at least a slight command of the language, and lands a job working as the live-in handyman in an apartment block, one of several dour, characterless towers on a drab housing estate populated by other poor and immigrants and overlorded by a criminal gang.

Audiard repeats a motif he already took on with his epic prison tale A Prophet (2009) as he depicts the fate of a member of an uneasily accepted social group – Algerian immigrants in the former, South Asians here – thrown into a Darwinian zone where to survive one must either turn every cheek or dedicate one’s self purely to the vicissitudes of battle. He also revisits a core theme from Rust and Bone (2012), in depicting a life-battered trio of people fusing into a rough approximation of a family and finding unexpected strength and reason to persist in the face of daunting ills. Much of Dheepan takes the more intimate focus of the latter as Audiard considers, with a certain spiky humour and strangeness, what happens when the fake family begins to operate more like a real one thanks to the quiet pressure of assumed mutual responsibility. Dheepan becomes working breadwinner and Yalini tries to operate as homemaker and solicitous minder to Illayaal. None of them quite fits their assumed role, however. Dheepan, a hardened fighter, yearns to be absorbed into the fabric of everyday life and wears his assumed workaday fidelity like a second skin, even as Yalini, half-charmed, half-wary, recognises his lack of a sense of humour reveals a deeper discomfort with the sign-play of normality and his detachment from banal luxuries: he’s happiest, and shows signs of the low-guttering but still potentially hot flame within him, as he retreats into his tool closet and sings along to songs from the homeland, whilst he has dreams of an elephant, at once deistically benign and threatening, glaring down at him through a leafy canopy, perhaps the eye of Ganesh boring into his damaged but still yearning soul.

Yalini herself is a spiky, independent woman with no maternal experience, and doesn’t know how to handle the intelligent but nervy Illayaal, who becomes so outraged by the heedlessly joyful play of her new schoolmates after they’ve rejected her that she attacks one in a fuming fit. Within the complications of narrative and character, Audiard sets out to illustrate the deepest and most gruelling aspect of the act of becoming a migrant, a shift not just in locale, economic strata, or even language, but in seeing, thinking, experiencing – his protagonists being forced to adopt roles and personas on the individual level gives Audiard a strong metaphor for the larger experience of being transplanted and learning to cope through a careful balance of mimicry, solicitude, and detachment. The motif of nuclear family fusion is one that Steven Spielberg has of course long been fond of, although Audiard’s references here more immediately invoke Francis Coppola’s The Godfatherfilms, as he depicts the moment when the migrant ceases to simply to keep their head down in their adopted society but begins to carve out turf within it for the sake of self and like, and also Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) as the former warrior turns his sights on the iniquitous in peacetime, blurring the line between righteous action and maniacal, PTSD-fuelled expiation. Or perhaps it’s more Paul Schrader as a whole Audiard wants to evoke, as the more righteous rampage of Rolling Thunder (1977) is called to mind once Dheepan is stirred to use his real tactical and fighting skills.

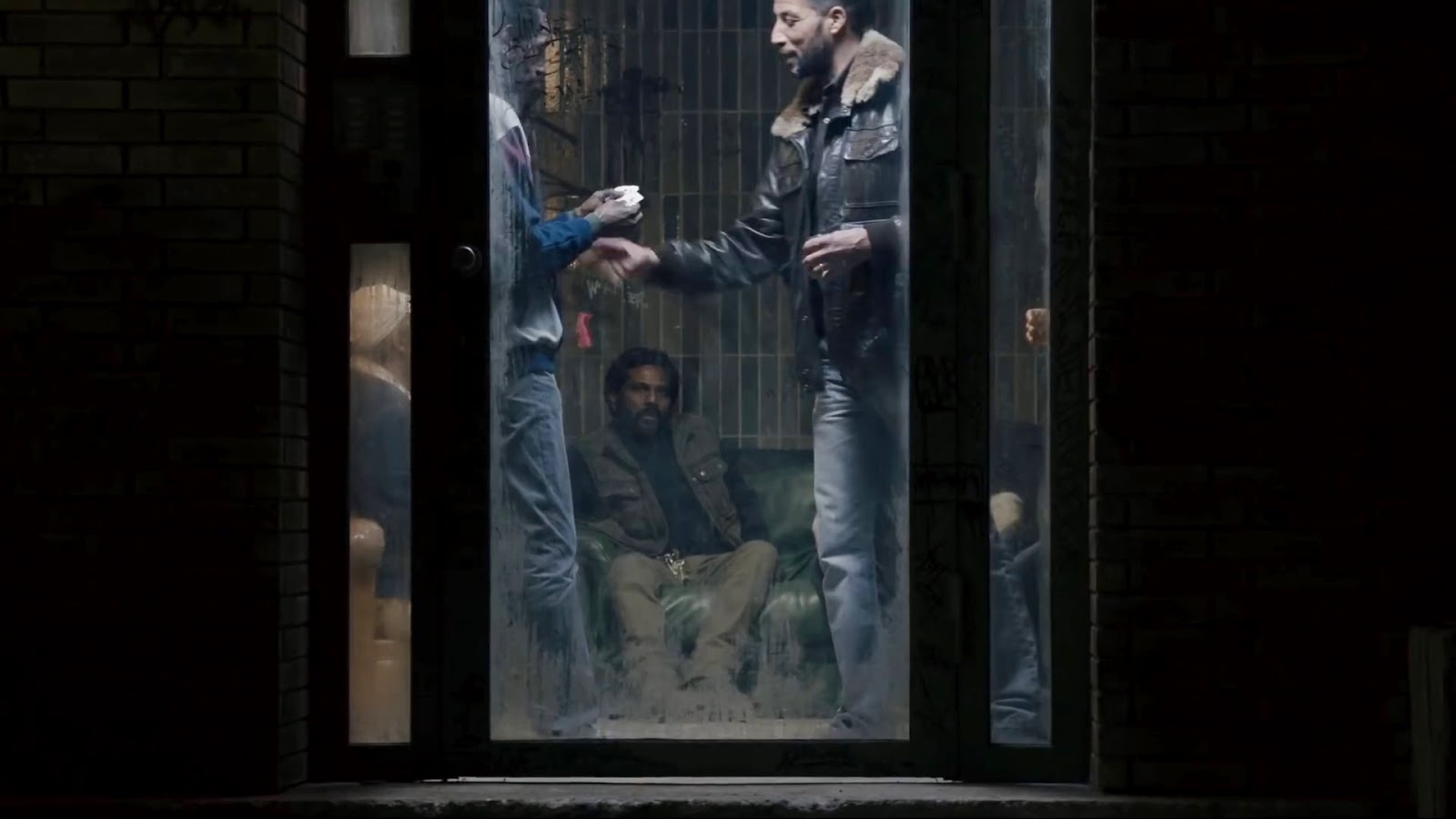

The main problem here is that Audiard tries to tell two stories that don’t quite fit together, or at least not the way Audiard handles them. For the most part he concentrates on the experience of wrenching shifts of cultural reflex and the interaction of the fake clan, absorbed in the nuances of their lives and evolving allegiances, like the gently sexy moment when Dheepan and Yalini become actual lovers. Meanwhile Yalini, to supplement the “family” income, takes a job as cook and cleaner for an elderly man, Mr Habib (Faouzi Bensaïdi), father of the local drug gang kingpin. Brahim (Vincent Rottiers), who’s just out of jail and sports an ankle monitor. At first the gang-run building, with its rooftop and doorway guardians all armed to the teeth, is like a perverse television show or installation art piece that Dheepan and family stare at in bewilderment from their curtain-less window. Yalini finds herself drawn into uneasy but diplomatic conversations with Brahim, embodying as they do two different generations of a similar experience and also two different ways of dealing with it, and their conversations are a strange mixture of mutual incomprehension – the only language they share is a smattering of English – and also reflexive understanding, as well as threat, as Yalini always knows she on thin ice.

As well as indicting the dumping grounds of the displaced and dispossessed, Audiard coolly notes other kinds of migration and exploitation going on concurrently, as the gang likes to employ white French kids from poor towns and regional areas as their mules, heavies, and pushers. Meanwhile Dheepan encounters some of his comrades who have followed on the same refugee trail but still hope to resume their struggle at some point, and Dheepan risks the wrath of his former commander when he refuses to becomes involved, explaining his war is over. But Brahim’s return to the estate brings conflict in his wake, as rivals try to assassinate him, turning the courts into something terrifyingly like the war zones Dheepan, Yalini, and Illayaal have escaped. Yalini’s first instinct is to flee whilst Dheepan becomes convinced he must draw a line, literally – he marks a divide between his tower block and the one controlled by Brahim’s gang, declaring they’re not to go shooting their guns off over this border again. Audiard’s visual syntax communicates a toey, ever so slightly paranoid, cringing perspective with his brittle hand-held camerawork, interpolated with moments of smooth motion and centred, calm visuals that communicate the moments of equilibrium, peace, and pensive remove, like a gently arcing drone shot surveying Dheepan walking through his adopted world when all is going well, and the dreamy refrains of his vision of the elephant.

Audiard makes a motif of characters melting in and out of darkness, usually at the gates of phases of experience, as when the family is on the boat leaving Sri Lanka, a moment of transformation that gives way surreally to the sight of Dheepan and others selling novelties on the streets with flashing animal ears perched on their head—an inspired encapsulation of the attractive flash of the first world and the infantalization imposed on immigrants and other fringe dwellers. Or when Dheepan follows Yalini into the bedroom as she undresses. By contrast, Audiard’s action finale is startlingly executed in one of his most visually adventurous sequences to date, filmed in a series of shots that manage at once to be tightly focused on Dheepan’s person but also oblique and ambiguous, experienced in raw immediacy but through the fog of adrenalin and twisting, chaotic perspective, like a sequence out of one of Gareth Evans’ The Raid films reshot as impressionist fugue. But for all its qualities, Dheepan isn’t as cumulatively powerful and convincing as either A Prophet or Rust and Bone. Both those films felt like highwire acts, relying purely on creative nerve to hold them together. The former blended grimy immediacy and insights into its milieu with a storyline of near-mythic simplicity in watching the weak become strong. The latter saw Audiard daring himself to stretch his tale ever taller, into ever more odd and visceral places in his desire to grasp the essence of the burning life force. Here the models he quotes result in narrative swerves that don’t feel that well thought-through and rushed when they arrive. Personally I wished Audiard had made more of the edge of Loach-esque people-power Dheepan starts to assemble to push out the gangs, and the film probably required the less hurried expanse of A Prophet’s running time to build to the catharsis Audiard tries provide, for Dheepanlurches suddenly into crisis mode and leaves off with a coda that feels unearned. That said, this is for the most part an intelligent, deceptively high-tensile piece of cinema.