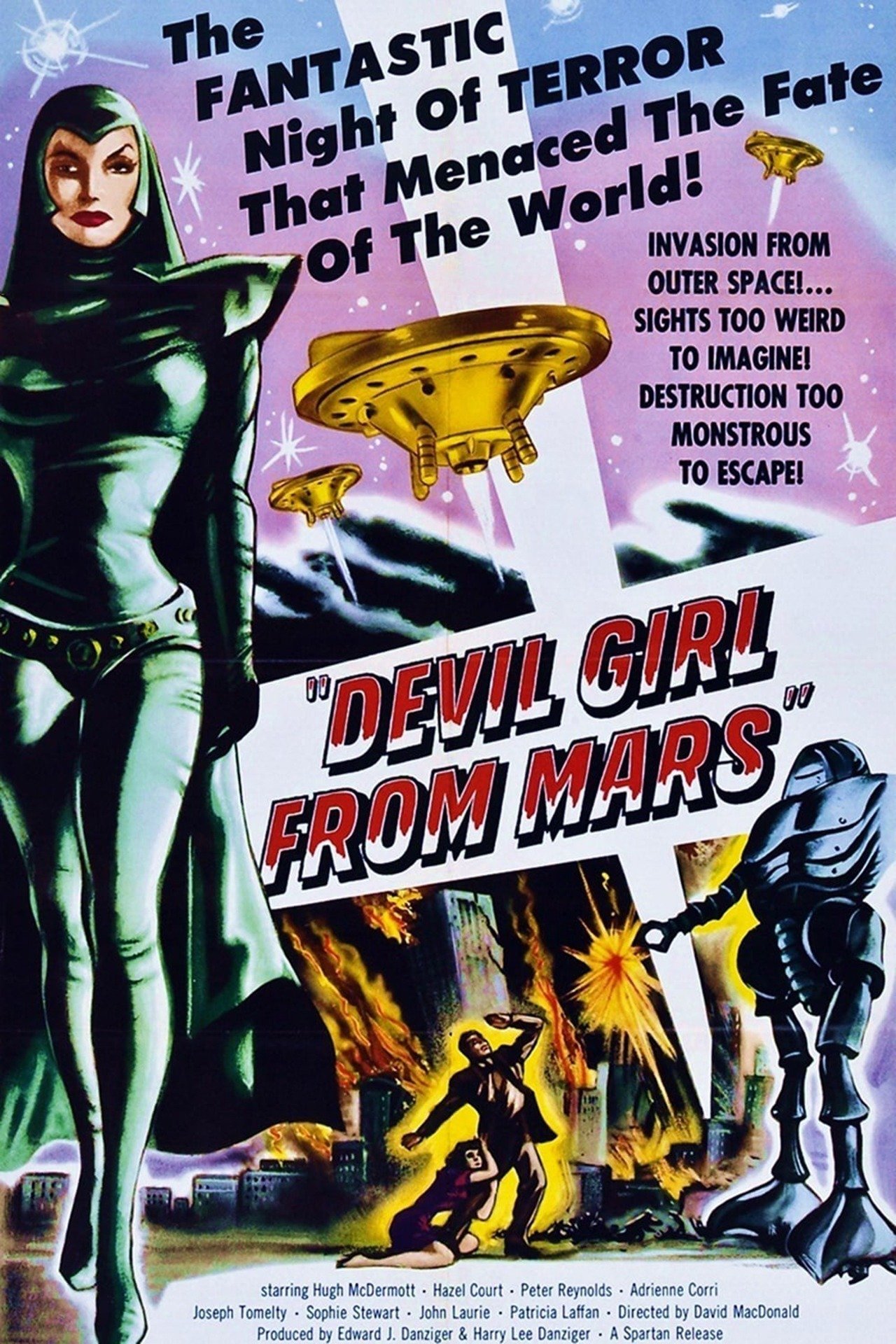

Devil Girl From Mars (1954) Movie

In spite of plentiful competition, few film titles of 1950s are as strikingly, screamingly, irresistibly camp as Devil Girl From Mars, a low-budget British attempt to get in on the decade’s sci-fi craze.

This contender from director David MacDonald came out a year before the film adaptation of Nigel Kneale’s The Quatermass Xperiment properly defined a peculiarly British version of sci-fi cinema, but there is something to this film’s heavily contrasted visuals, and sense of flailing impotence in the face of overwhelming threat, which presages the parochial genre. Devil Girl From Mars is, sadly, less Nigel Kneale than Nigel Tufnell.

Many of the cheaper ‘50s sci-fi flicks tried to dress up their seamy wares with soft-core titillation and incidental sexism, and Devil Girl From Mars, with its PVC-clad, mini-skirted dominatrix from outer space having come to Earth to search for masculine breeding stock, encapsulates a dichotomy of a fetishist dominant femininity and terror of gynocracy, a mixture that often bobs up in genre films from this era.

But describing this film in such a fashion places me at risk making it sound entertaining in a trashy kind of way. In fact, it’s not really trashy, and it’s not entertaining either. It is, rather, dull, slow, self-serious, and betrays its origins as a play so baldly you can practically hear the smoker’s cough of the stage hand and smell the stale tea in the dressing room kettle. Like Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Man From Planet X (1950), this film chooses rural Scotland as the place where mankind and alien meet; but unlike Ulmer’s even cheaper film, director MacDonald can’t wring much atmosphere out of this felicitous locale.

Which is a pity, because the essential situation is close to that of the most impressive of MacDonald’s films I’ve seen, the claustrophobic thriller Snowbound (1948), but this is closer in result to some of his other credits, like the awful biopic The Bad Lord Byron (1949), and the better but still very stodgy Christopher Columbus (1949).

The action is mostly restricted to a homey, isolated inn, kept by a cheerily bickering couple, the Jamiesons (John Laurie and Sophie Stewart). Reports of strange fiery objects falling from the sky in the area bring scientist Professor Hennessey (Joseph Tomelty) and journalist Michael Carter (Hugh McDermott) to the inn.

Amongst the inn’s few guests is model Ellen Prestwick (Hazel Court), who’s on the run from heartbreak in London, whilst barmaid Doris (Adrienne Corri) has taken a job so she can be close to her former boyfriend Robert Justin (Peter Reynolds), who’s in jail nearby for killing his domineering wife. Justin chooses the same night to bust out and pose as an itinerant eager to work for his keep at the inn, as the cast find themselves confronted by the eponymous black-clad femme fatale, Nyah (Patricia Laffan).

Nyah parks her spaceship nearby and explains she’s been forced to make an emergency stopover by engine trouble. Because she had planned to land in London, Nyah is reduced to showing off her incredible power and scientific advancement for the sake of cowering the collective at the inn, including parading her robot, which, sadly, evokes not its clear precursor, Gort from The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951), but a ‘30s radio with legs and amusing vestigial arms. The model work for Nyah’s spaceship and the sets depicting it are standard-issue for ‘50s interstellar craft, all sliding external hatches and glowing recessed lights to suggest mysterious power sources without anything our puny ape minds would think of as controls.

It is diverting to see Court and Corri together in this prototypical work, as both would become popular faces in the oncoming boom of British horror and sci-fi films. Laffan’s role exploits her minor stardom after playing Poppaea in Quo Vadis? (1951), where she was the decadent, feline opposite to Deborah Kerr’s goody-goody Christian lass; here she’s pitched to offset Corri’s emotive, selfless reject and Court’s anguished professional beauty, parading into the film clad in her fetishist’s delight garb.

Nyah’s costume, with modified Inquisitor’s helmet, black glistening cape, and threateningly proffered penis-envy-powered ray-gun, provided ‘50s genre cinema with one of its purest, most easily excerpted icons: Nyah has stalked her way through countless genre surveys and television encomiums to retro cheese. But the fun provided by Nyah’s outlandish look drains away after about five minutes, and in spite of the high-contrast gender-coding, Nyah proves less an icon of insidious, order-destroying feminism than just another high-toned, big-talking alien invader, one who continually promises to astound mankind with infinitely superior technology, whilst failing to properly browbeat the bunch of losers she’s confronted with.

She also flies about in a spaceship that can, apparently, be sabotaged with a good hard punch to the reactor. The film’s mid-section is little more than a succession of sequences in which Nyah, after dismissing feeble acts of resistance, shows off some piece of hardware to browbeat the characters, like history’s most evil Tupperware party host.

The script, by James Eastwood from the play he wrote with John C. Mather, promises early on to offer fleshed-out characterisation and contrived but potentially interesting dramatic intersections, but as it plays out the characters are revealed as insipid, the dialogue painfully dull, and the drama weakly developed. Time seems to stand still as Carter and Ellen romance, and it’s not because Nyah has some beam that can make that happen, but merely because of boredom. Nyah hypnotises Julian to go and do her evil bidding, which is, apparently, that he should sit in an upstairs room glowering for the next half-hour of running time.

What is obvious is that the original play structure was barely revised, in spite of the occasional moves outside to the vicinity of the space craft, as most of the action takes place in the inn’s dining room, and Nyah repeatedly enters stage left, marching in through the inn’s French windows, to speak haughtily at the Earthlings and deliver some sort of ultimatum, and then leaves them to argue, fret, form swift bonds, and try their various lame attempts to outsmart and kill her.

The climax is predictable, nay, inevitable from the first moment Justin is introduced, as he, the doomed transgressive outcast, is the logical choice to go on a suicide mission, having proved he’s competent at eliminating bitchy females. I do jest, but the film does not. Still, there’s an ever so slight hint of something deeper, a sense of pubescent forbidden delights in the way Nyah takes local boy Tommy (Anthony Richmond) under her wing, or cape, and leads him into her spaceship for a tour, a metaphorical induction into mysteries of adulthood for the lad in a moment aimed exactly at the disquieting nexus of maternal and sexual interest, a point which is fleshed out when Nyah later confirms she plans to take Tommy back to Mars as her choice for breeding stock, unless another, more developed male volunteers to take his place. Fortunately, Julian is ready to prove that a human male would rather die than accept the status of intergalactic man-ho with nothing to do other than service a race of latex-clad hotties.