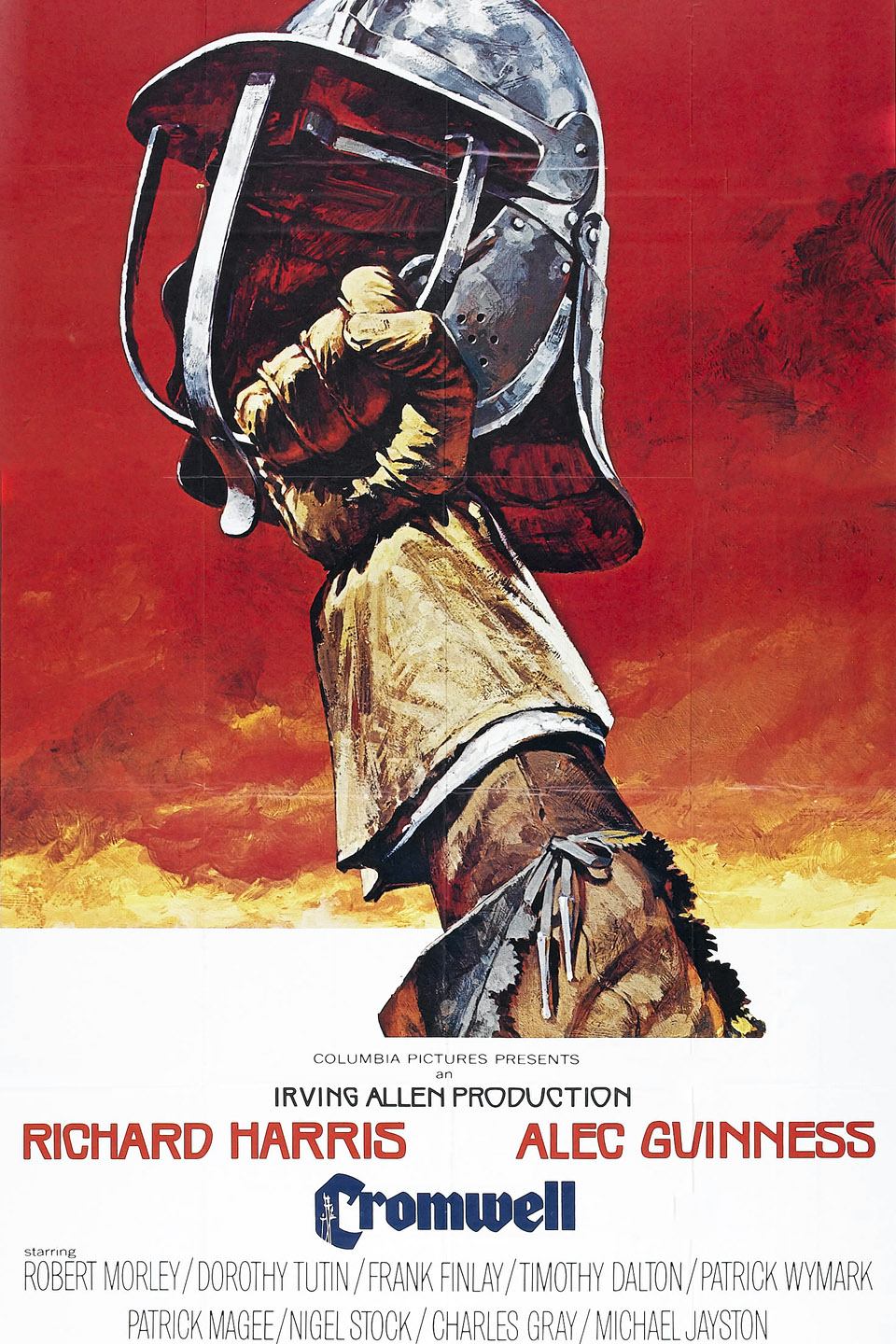

Cromwell (1970) Movie

The late 1960s and very early 1970s saw a last bloom of a short-lived genre, that of the serious historical epic, with films that tried to combine the traditional wealth of pageantry and expansive action that had long defined Hollywood’s understanding of the past, with the more sober, literate model laid out by the likes of Becket (1964) and A Man for All Seasons (1966).

Most of these were flops, and few gained any real critical regard, although some had real worth: either way their number included the likes of Charles Jarrott’s fine Anne of the Thousand Days (1968), Clive Donner’s ill-advised Alfred the Great (1969), Sergei Bondarchuk’s impressive Waterloo, James Clavell’s inquisitive The Last Valley, and Franklin Schaffner’s top-heavy Nicholas and Alexandra (all 1971). The lack of success of these films helped in large part to doom Stanley Kubrick’s storied Napoleon project, and made him turn to a more focused historical canvas with Barry Lyndon (1975).

Cromwell, helmed by experienced British craftsman Ken Hughes, was one of the most ambitious entries in this cycle. Hughes’ big previous hit had been the candy-coloured children’s film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). The journey from celebrating Toot Sweets to exploring the underpinnings of the English Civil War might have seemed a long one, but Hughes’ best-regarded film up until he made this had probably been The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960), and the historical material he tackled here offered an even greater scope of drama invoking questions of the present through the travails of the past: where Trials had been one of battery of combination punches tackling judicial treatment of homosexuality in the early ‘60s along with Victim (1961) and another Wilde biopic, Oscar Wilde (1960), Cromwell embraces the radicalism of the later decade and reflects it through the prism of the Lord Protector’s righteous but pulverising zeal in another time of upheaval and furiously questioned social precepts.

Cromwell is beset by confused approaches to its subject matter however, attempting to present a shaded portrait of its eponymous hero as a conscientious traditionalist pushed first into radicalism and then into repeating the mistakes of his enemies, finally transcending hypocrisy through the ardour of his idealism. But Hughes fudges facts and skews his portrait of Oliver Cromwell, who had elements of the visionary to him but was hardly a prototypical 20th-century liberal, as a man operating according to his period’s prejudices but driven ultimately towards far-sighted, democratising impulses.

The best thing that can be said about Cromwell as an historical study is that it does manage, with some art, to explain and encompass so much of an incredibly complex period, and explore the issues that started the war and led to Charles I’s beheading: the central schism between the King and Parliament, the background of war with Scotland and Irish religious rebels, the reasons for Charles’ intransigence, and the acts by the King that provoked his conviction and execution; are all laid out in largely coherent terms. To achieve its wider goals, however, Cromwell takes vast liberties with the historical record, mostly to give Cromwell a larger role in the lead-up to the Civil War than he really had.

Such flourishes include making him one of the five members of Parliament Charles tried to have arrested for treason, giving him a higher rank and having him participate in the Battle of Edgehill which he actually didn’t make it to in time, and having him lecture Charles on the idea of introducing democracy into the English political landscape, an idea Charles (Alec Guinness) dismisses here as “a Greek drollery.” Cromwell’s son Oliver II (Richard Cornish) is depicted as dying in the Battle of Naseby when he died of disease a year later, and Hughes is sloppy enough to show Harris standing before Oliver II’s grave with the actual date of his death clearly marked.

One can’t dismiss these distortions too blithely, but the points Hughes tries to make are valid, as is his method of quasi-Shakespearean compression: the war involved a great personal cost for Cromwell, he stood amongst a number of men who took a colossal, risky, and principled step in rebelling against royal authority at a time when the general tide of European government seemed to moving ever more implacably towards absolutism. Hughes also ably attempts to concatenate a vast war’s progress into two representations of battle rather than exact historical recreations.

More troubling, however, is the way the film avoids dealing with Cromwell’s infamously brutal repression of the Irish Catholic rebels, and the devolution of England during the Commonwealth into periods of absurd theocracy. The film fades out with Cromwell delivering a stagy tirade about bringing reform to the nation and building new institutions, as the face of what could be called responsible revolution. The slightly hollow final heroic lustre Hughes places around him doesn’t really do him any favours, however. Cromwell was a political warrior who gained victory in a far less preciously humanistic age than ours.

The steely, implacable man Patrick Wymark presented in Michael Reeves’ vivid and antipathetic anatomy of the Civil War era, Witchfinder General (1968), is arguably more convincing for all its brevity than Hughes’ and Harris’ windy fanatic. Cromwell is too often reduced to a sanctimonious, sweaty bellower, as Harris gets quite notably hoarse in many scenes from all the shouting, or, alternatively, a declaimer of low and breathily savage resolutions in close shots before dramatic scenes fade out, with lines like, “I will have this King’s head, aye, and the crown upon it!”

It’s not entirely Harris’ fault that the characterisation fails, and whatever else one can say, Harris tackles the role with compelling, bodily force, but his tendency to shout his way through roles in his more lacklustre late ‘70s and ‘80s films is certainly presaged here. Where a cooler regard for its subject might have benefited the film then, or a more engaged psychological portrait, this Cromwell is never less than adamantine in his iconic bluster.

However, the essential concept of Cromwell here has a certain authority: he’s portrayed as a battering ram of resolve, in an era clogged with feckless privilege, passionless professionalism, and musty self-interest. He channels the latent force of a repressed commonality and the shock of the new into a potent military and political force. Early in the film, Cromwell is offended by evidence of the vulgarisation of the English faith, stormily assaulting the altar of his local church when he sees it festooned with golden candlesticks and crucifix, as the King is under the influence of his French Catholic wife Henrietta Maria (Dorothy Tutin), who also preaches the necessity of unyielding royal prerogative to her husband.

The source of the elaborate paranoia for Catholicism in the English Protestant mind was indeed closely allied to awareness, as Cromwell states outright in the film, that it was tethered to the phenomenon of absolutism as practised in France. But Hughes stoops a little too close to suggesting that wars can be started by henpecked husbands bossed around by bitchy wives.

Tutin does a good job nonetheless of portraying her character’s faintly frightening blend of conceit and blind purpose, whilst Charles is stripped bare in his craven nature when he’s forced to execute his own partisan minister, the Earl of Strafford (Wymark) after she’s pushed them to try repressive tactics on the Parliament: “You see?” Charles demands of her, waving the execution warrant for the Earl at her in pathetic displacement of responsibility: “You see what you made me do?” Much like William Dieterle’s Juarez (1938), Cromwell is further destabilised as the narrative becomes dominated by a doomed royal’s journey to destruction.

Released from the necessity of playing a heroic icon and allowed free reign in his role, Guinness gives one of his best performances as Charles, a man of firmness and effete sensitivity sadly allied to a complete lack of guile, public charm, political sense, and sensible independent will. Unstoppable force and immovable object meet as Cromwell, having won the war and gained the trust of his soldiers and now determined to foist their will upon the King, is faced with Charles’ quiet refusal to countenance any such thing, even when every barrier between him and a vengeful foe has been flattened.

Another problem with Cromwell is that, intended as a three-hour film, it was hacked down to just over two, including the total removal of Felix Aylmer’s last role, and the gaps are often perceivable. Perhaps the awkwardness of its transitions and finale derive in part from this. On the other hand, the film moves at an admirably fast clip. Hughes uses some familiar devices in tracing Cromwell’s career: in a scene that evokes The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), he intervenes in a dispute between classes, as the Earl of Manchester (Robert Morley) cordons off common land for a sheep pen and has his men arrest protesting yeoman John Carter (Frank Finlay).

Carter later wanders into church during Cromwell’s anti-papal hissy fit having had his ear cut off in punishment, sparking Cromwell to an even greater rage: “God damn this King!” he declares, only for Hughes to make a neat jump-cut to Charles, smiling beatifically, praying in chapel. The proximity of the crude device to establish drama, in Carter’s disfigurement and appearance in the church, and the felicity of this cut, which brings to a fine point the violent disparity in world-view held by Cromwell and Charles and the religiously-informed certitude behind them, is indicative of the movie as a whole.

Cromwell finds his fate entwined with Manchester who, seemingly a pillar of the Royalist party, sides instead with the Puritans and other Parliamentary adherents, and becomes a leader in the army, whilst Carter becomes a ranking soldier, but gets himself hung, through Cromwell’s procedure of making the men draw lots, when he lends his voice to angry protests against negotiations with the King. Others in the Parliamentary cause include the temperate John Pym (Geoffrey Keen) and the fire-eating, ambitious Henry Ireton (Michael Jayston), who repeatedly presses Cromwell to move to extremes.

What sustains Cromwell in spite of its shakier dramatic qualities is the solidity of its production, the strength of its cast, and its visually strong storytelling, engaged with a punchy and physically convincing historical milieu. Photographed by the great Geoffrey Unsworth, the film’s pictorial palette strikes a balance between splendour and grit, capturing a society teetering mid-way between Renaissance and Enlightenment as it explores the mismatched architecture of London and the proto-modern apparel and sloganeering of the New Model Army.

Whilst hardly as incisive or creative in exploring the rhetorical style of the era as Ken Russell or Tony Richardson would have tried to be (or as Kevin Browlow succeeded with Winstanley, 1974), Hughes nonetheless evokes the furore and communal passion of a transformative moment. Particularly effective is a pageant-like scene as the country goes to war and Cromwell beholds preacher Hugh Peters (Patrick Magee), driven aloft a multitude of soldiers, preaching holy war with the aspect of a prophet-warrior out of Old Testament times, surrounded by banners that announce the birth of a new era in how political ideas are expressed and by whom.

The scene that pays off with Carter’s hanging likewise offers a hint of the newly empowered underclass gaining its voice in a moment of fractured certainties. It’s a real pity then that Hughes can only really articulate thematic heft in speeches. Similarly strong is a counterbalancing scene depicting the disintegration of patrician self-regard, as Charles mercilessly rebukes his flashy nephew Prince Rupert of the Rhine (Timothy Dalton) for abandoning the besieged city of Bristol, Rupert’s preening self-regard mitigated by genuine physical pain and belief he did the right thing, but wracked by Charles’ peevish contempt and flailing self-pity as he comprehends ultimate defeat and, as he did with Henrietta Maria earlier, taking out his feelings and failings on another.

Dalton’s Rupert is one of the film’s fleeting pleasures, a showy peacock of a blue-blood, full of all the strutting arrogance and romantic dash one would expect of the exemplar of the Cavalier side in the war, a sneaky relief from the tight-lipped grit of the Roundheads and their starkly serious wardrobe.

This is one of those roles that Dalton always seemed to appear in before his impressive but ill-fated stint as James Bond, bringing swashbuckling flash and plummy theatre to cinema screens in an age dominated by squirrely method actors, doomed by his capacity to play anachronistic roles to be second fiddle. The mid-section of Cromwell is buoyed by excellent battle scenes that, whilst not entirely accurate depictions of the specific battles, still capture in detail the tactics of the era, particularly good in visualising Cromwell’s approach to bluffing and trapping his enemy as at Naseby he engages with the cavalry of Prince Rupert, whom he suckers into a pincer move and sends scurrying from the field after close combat.

As in his crowd scenes, Hughes displays impressive craft and skill for clear analytical editing as well as forceful staging in the battles, as the close melees and cannon barrages really seem concussively violent, and he gives glimpses of the primitive but lethal duels of matchlock riflemen and pike-wielding infantry. One great shot from a camera slung on the underside of a cavalry horse in a charge captures the pounding force of a charge.

The last third of film deals, inevitably and in detailed care, with Charles’ trial and execution, and here Guinness’ performance really shines as Charles refuses to be swayed from his imperial self-regard even on the scaffold, and Cromwell becomes all the more remorseless in the face of his fretful fellows, like Sir Thomas Fairfax (Douglas Wilmer), evoking the similar frustration in Marlon Brando for his inability to wipe the smug smile of bully Trevor Howard’s face in Mutiny on the Bounty (1962).

Charles goes to his death with enviable grace, whilst Cromwell, turned into a glowering Darth Vader in black cap and hat, can only shout reassurances to his fellow Regicides that they have acted legally whilst treading away in moral and physical exhaustion. Cromwell retreats to sit before his fire with glazed depression before being called back into the political fray as the new Republic proves as corruptible as the old Monarchy. The film ends with its divided spirit again on show, as Cromwell clears out the Parliament, depicted as devolving into corrupt theatre run by oligarchs like Manchester and Fairfax.

Cromwell thus assumes the mantle of dictator, tossing the Royal mace off the table, and he’s left alone in the Commons, having repeated the King’s crime and gutted the political system of his country, leaving only his own will. Hughes zooms out to show Cromwell alone in the vast and draughty hall, but the voiceover gives a mealy reassurance that Cromwell has helped give birth to modernity.

The disparity of message and fundamental point here is deeply ironic, but Hughes exacerbates rather than explores the irony, and the film finally lacks to courage to present a lucid portrait of a tragic hero. Cromwell is an entertaining and substantial ride through a great epoch, but the great film about that epoch is yet to be made. And what Cromwell did at Drogheda, the infamous Mae West camp-fest Sextette (1978) did to Ken Hughes’ directing career.