We’re moving into an age in which institutionalised gay marriage is becoming a norm. Concussion, the debut film from Stacie Passon, surely operates from a perspective that the familiarity of the phenomenon is already a given, certainly in the tamer hinterlands of the larger American cities. Concussion unfussily presents a tale of marital infidelity that is also sexual exploration and self-discovery, albeit it in the context of a lesbian marriage. A marriage which is, in its rhythms of staid routine, companionship, child-rearing and a sense of enveloping security that’s both reassuring and suffocating, utterly normal. This notion lends Concussion some of its originality, the conviction that this aspect of its focus is the least radical. The general proposition here could easily be described as Belle du Jour (1967) with a queer twist. But there are subtle and unsubtle differences. Bunuel’s film was littered with surrealist digressions amidst filmmaking rendered with the glossy sheen of its era’s high-end cinema, whereas Passon’s approach sits comfortably in contemporary Indieville with the most minimalist stylistic flourishes and occasional jolts of aptly cool classic rock, like some Bowie to set the scene. Bunuel’s subject was female sexuality trying to escape cast iron bourgeois armour by engaging in prostitution but noted with irony how this only extended its own perversion (whilst fetishizing that perversion, of course). Passon’s subject is more contemporary, probing how to reconcile committed relationships with desires that cannot be met by those relationships. To wit, the talented Robin Weigert (who was, I recall, easily the best thing about Steven Soderbergh’s The Good German, 2006) plays Abby, a former interior decorator and renocator who’s been playing the housewife to her two children with Kate (Julie Fain Lawrence), but at the start of the film has just reached the end of her tether when her son’s roughhousing has given her a nasty gash and the title condition, and she alternates angry abuse of the kids and sobbing frustration.

Abby feels encaged not just by her rambunctious children but by her partner’s disinterest in sex, and her attempts to express her arty, transgressive side in writing is shot down when she tries to submit a candid article to a bland mothering magazine run by her gym pal, and social circle queen bee, Pru (Janel Moloney). To escape her growing unease and ugly epiphanies stirred by her injury, Abby decides to take on a renovation project, fixing up a gutted apartment in a near-empty building in a downtown urban area. She works on this with Justin (Johnathan Tchaikovsky), a younger hipster. Abby tries to sate her sexual frustration by visiting a prostitute, but finds the encounter with the drug-using demimondaine a discomforting turn-off. When she mentions this to Justin, who’s at ease in the city’s erotic nightlife, he has his girlfriend, a pre-law college student who works as a high-class pimp and is known only as “The Girl” (Emily Kinney), to dig up a better encounter for her. This leads to a night with the confident and talented Gretchen (Kate Rogal), and Abby who soon makes the jump into sex work herself. She takes on a variety of clients, many of whom are young, inexperienced, and anxious rich kids unable or unwilling to engage their desires in other ways, like a hefty young student (Daria Feneis) who’s too caged by anxiety over her weight. Abby takes to this sideline like a duck to water but finds keeping it secret difficult, particularly when one of her clients turns out to be a woman from her own social circle, Sam (Maggie Siff), who had already caught Abby’s roving eye across the rows of exercise bikes at the local gym.

Passon’s achievement here is noteworthy but uneven. She effortlessly processes the more difficult feats of her project, turning Abby’s jobs into etudes possessing cool but genuine eroticism, mysterious compassion and curiosity, and a breezy, businesslike detachment all at once. Abby’s encounters with her clients are easily the most interesting aspect of the film, as she brushes against varieties of anxious and confused women who are seeking to liberate an aspect of themselves, whilst Abby does the same thing. Passon blurs the line between prostitute and client, the giver and receiver of pleasure. It becomes clear that Abby is an ideal sex worker, someone with a capacity to locate passion in herself with anyone, and to pass that along like a gift like a balm. Passon’s shooting and cutting are at their best here, touching the outer edges of abstraction in visual textures in the way she films encountering bodies near and on the bed, which comes to occupy the under-renovation apartment with a kind of theatrical singularity. Slowly the apartment grows into an expression of Abby’s tastes and distinct personality just as she grows with the job, but thankfully the metaphor of personal, lifestyle, and real estate renovation coinciding isn’t pushed too hard, but allowed to exist as a background idea, as well as offering a clever major plot device reminiscent of Last Tango in Paris (1972), still the long shadow in this mode of filmmaking.

The script fails to connect the facets of Passon’s dramatic interests, however. The wry comedy of modern manners enacted between Stacie and her contacts in the prostitution world, the domestic tragicomedy played out with Kate, the girl-crush fantasy of Abby’s connection with Sam, and the intimate fire of the sex scenes all seem to exist as slightly distinct movies, as if Passon really hadn’t quite decided which story she wanted to tell. At its best, Concussion suggests a ruder-minded riposte to Lisa Cholodenko’s insufferable The Kids Are All Right (2010), certainly taking place in much the same neo-suburbia as that film and wrestling with a similar proposition that although lesbian couples ironically seem best suited today to fulfil the ideal of the suburbanite nuclear family, instability still lies beneath all. Passon avoids the canard of an affair with a man with dexterity and a certain good humour: one of her wittier scenes has Abby regaling one of her curious male friends with a bogus anecdote of pornographic self-discovery, which both wryly chuckle over when she can’t sustain the act: “That was turning me on,” he says, self-deprecatingly. More importantly, Passon eagerly connects her material with the strong tradition represented by writers like John Cheever and Joyce Carol Oates of tales set in leafy prosperous commuter belts where the oceans of smug repress lodes of quiescent desire. Unlike the best works of such traditions, however, the liberationist zeitgeist Passon is exploring forbids any dramatic combustion, however, because that would smack of the reactionary.

Laila Robins has a small but effective role as another of Abby’s clients, one who’s older than her and seems much more effectively independent, who left her husband because he was attentive and conceding to a fault in a fashion that felt disengaged in a peculiar, disturbing manner, as if by answering all of her needs he was delivered from having to actually have interest in them. Kate eventually discovers Abby’s sideline, revealing a variety of truly human, perhaps inevitable hypocrisy: Kate had earlier sharply dismissed the sense behind Sam and her husband’s breakup by implying that sexual freedom should be a part of a marriage, replying to Abby’s explanation that a friend is getting a divorce because she “couldn’t breathe” with, “So she should go breathe. It’s sex, grow up.” When confronted by her own partner’s obedience to this precept, however, Kate cannot help but be dreadfully hurt. Passon has Kate confessing to virtual asexuality: “I don’t want anyone,” she retorts to Abby’s accusation that she doesn’t have desire for her. This introduces an interesting notion, but also lets Abby off the hook a bit too easily. Abby’s pining for Sam and its surprise consummation has a strong hint of idle fantasy reminiscent of much less sophisticated gay porn where the hot pool boy turns out to be totally bi, and more to the point it doesn’t lead anywhere interesting. Sam later, when they run into each-other in a casual encounter, describes it as a lovely event they can both swap private smiles over in years to come, a touch that should come loaded with good-humoured pathos but only shows up how dull this plotline is, in spite of having an actress as weapons-grade hot as Siff on hand. The film’s narrative remains, like its heroine, a bit too dilettante-ish, allowing Abby to skim the surface of a volatile demimonde that stands in such raw contrast to her native territory.

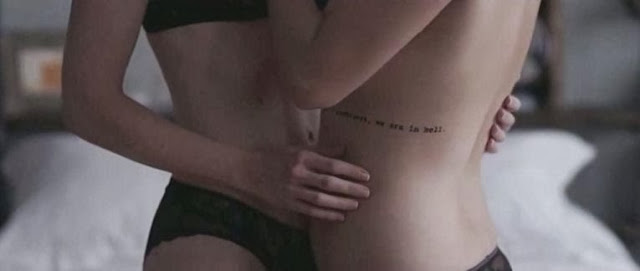

Still, Abby’s adventures with the various women exploring each-other’s bodies with a sense of discovery, retain a grasp on the sensuality of eased frustration and dissipating anxiety. Abby learns to fearlessly seduce damaged women and average ones alike. There’s no sense of patronisation or morbidity to these encounters, only an open sense of the peculiar benediction of intimacy. Passon offers one encounter that pushes Abby far out of her comfort range, with a woman who seems to want to wrestle her into submission, a moment that achieves a genuine note of discomfort and weirdness and is dropped in as a cunningly jagged flashback, a moment that reveals what the whole film could have accomplished and also shows up some of the blander, less focused passages. Perhaps Passon’s keenest image also contains an essential thesis, a close-up of Abby in an embrace with a client with a scarred breast and a tattooed quote from poet Adrienne Rich: “Without tenderness, we are in hell.” Passon’s directing style keeps everything muted and orderly without major ruptures or changes of tone, which means that the film maintains an even temperament, but the crisply photographed natural light through glass effects start to feel as drably tasteful as the greys Abby is made fun of for preferring in her décor. But this doesn’t obscure the emotional core of the film, poignantly apparent when Kate finds Abby sprawled naked on a bed after a tussle with a client, and half-angrily, half-pathetically asks her to put on some clothes. The film’s secret weapon is its often dry dialogue and keen feel for interpersonal humour: Justin replying to Abby’s decision that “I think my hooker name should be Eleanor” with “My dick just shrank.” The Girl’s garrulous explanations of how she got into her business and her sole piece of advice to neophyte prostitute Abby : “Moisturize – I dunno, that’s what my mom always told me.” Abby’s amusing reading assignments to her most body-challenged client. Most particularly Kate, after Abby’s explanation that she was “breathing,” retorting with acerbic but also actually forgiving pith, “You must be out of breath.” O brave new world.