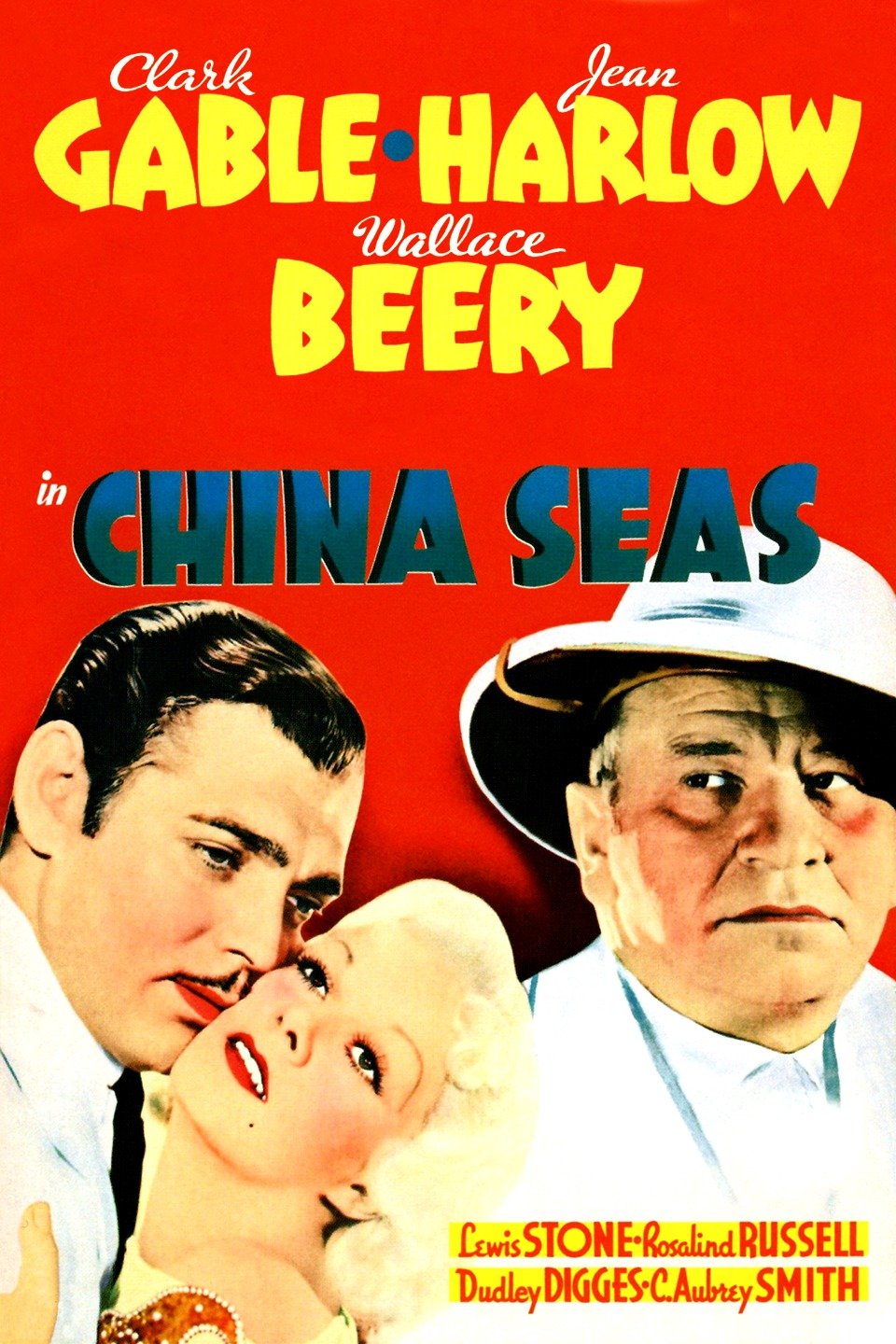

A shiny nugget of Old Hollywood entertainment, China Seas takes a standard exotic adventure tale and setting and marries it to raw star power and the proud but still pithy craftsmanship of a film industry at its zenith.

Clark Gable, perhaps warming up for Fletcher Christian, bothers not with affecting an accent as he plays Alan Gaskell, former British officer and gentleman, now captain of the Kin Lung, a passenger and cargo vessel making the run from Hong Kong to Singapore. Gaskell is a famously grouchy, demanding hard-ass equally feared and loved by his crew and employers, first introduced working off a hangover after a long and well-juiced break from his bouts with the ocean.

Jean Harlow is his favoured shore-leave pal, a garrulous, good-hearted floozy dubbed China Doll who’s stuck on this sailor boy. When she signs aboard his ship to make the voyage to Singapore, she’s left aghast when a ghost from his past catches his eye: Sybil (Rosalind Russell), his old lover from Blighty. Gaskell ran to the far side of the globe lest their adulterous affair be uncovered and to outrun heartbreak, but now newly-single Sybil has tracked him down to restore him to the bosom of English domesticity. China Doll reacts with displays of pique, trying to inflict embarrassment on Gaskell and Sybil but instead only managing degrade herself in the eyes of both her flame and the rest of the ship’s selection of international flotsam.

Around the romantic triangle runs a flotilla of colourful characterisation by a heavy-hitter cast of ‘30s actors. Wallace Beery is one of Gable’s crew, Jamesy McArdle, a bullish but covertly romantic lunk given to anaesthetising livestock with drugs and secretly conspiring with a gang of pirates to have the ship raided for a consignment of bullion stowed aboard. C. Aubrey Smith is the line’s owner, gruffly fond of Gaskell (everything Smith ever did was gruff, of course) and appalled that he might chuck over the chance to be his successor and retreat for a life of sitting by the fire.

Akim Tamiroff, pate awash with hair grease and face still baby-smooth, plays Romanoff, a White Russian roué romancing an American tourist (Lillian Bond) under her husband’s nose. Lewis Stone is former captain Davids, a nerve-shot relic serving now under Gaskell, having been disgraced by being the only survivor of a pirate attack. Soo Yong is Yu-Lan, a worldly but snotty socialite. Robert Benchley patents his sozzled avatar of the intelligentsia act, stumbling through the film as a boozy writer who barely exists on the same plane of reality as the rest of the passengers.

Hattie McDaniel has a brief but funny role as China Doll’s wiseacre companion who wants to inherit her cast-off racy dresses: the two actresses suggest nascent chemistry together that could in a different time have been spun into a long-running buddy comedy series. Russell, still some years before her liberating brush with farce on The Women (1939), is stuck playing politely dull refinement, sounding board for the audience to delight in Harlow’s fraught destabilisation tactics and outright mockery of the hoity types about her, part class rebel and part Harpo Marx with va-va-voom.

The embrace of MGM’s production gloss on this kind of movie could have been onerous, but China Seas crackles with a blend of efficiency in execution and organic sprawl. Director Tay Garnett keeps everything well-oiled. It evokes such works of ripe exotica as Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express (1931) and The Shanghai Gesture (1941) in story essentials and setting, but feels closer to pre-code films like Union Depot (1932) and evident precursor Grand Hotel (1932), rather than Sternberg’s neverland fantasias.

China Seas captures a sense of time and place with all the fecund, cosmopolitan energy of the inter-war period (and its cinema), its wobbling hierarchies and geopolitical patterns described in microcosm, this meeting place of East and West considered as the anatomy of a great and fertile chimera, a place where values are recast and discarded according to the moment’s logic. The film treats its audience like passengers on the Kin Lung, privy to a passing horizon and a host of vignettes comic and exotic—Gaskell’s dubious but amusing piece of street wisdom used to unmask some pirates posing as women, the moon-faced Chinese steward wielding a Tommy gun, Benchley trying to smoke a cigarette in the midst of a typhoon, pounding waves washing a would-be rescuer away repeatedly whilst he remains stewed and oblivious.

It’s less a straight melodrama than a tapestry, replete not just with heroes and villains and stakes and dramatic impetus, but also completely distracted and disinterested people, unruly human components in a shuddering mechanism. China Seas betrays the oncoming age of the Production Code as it wiggles through the rapidly closing door, reuniting Gable and Harlow after their hot-and-heavy dalliances on John Ford’s Red Dust (1932) and recasting the three-way travail of that film which also saw Gable’s interest gravitating from Harlow to an interloping lady of finer breeding.

But here Gable’s embodiment of a man aspiring to the pallid virtues of communal and conjugal acceptability is more reminiscent of Hollywood’s own yearning for such respectable climes, whilst Harlow’s high-calibre sex appeal, mediated by her ever-evolving skills as an actress, is rendered more sentimental as China Doll flounders with romantic rejection and vengefully turns to the dark side to earn a crust of payback. Garnett does let a wardrobe malfunction slip by almost subliminally when China Doll has a tiff with McArdle, like a farewell for the time being to any trace of Harlow’s famously oft-braless bravado and its place in Hollywood film.

Of course the element that links this film to Sternberg and Howard Hawks is co-screenwriter Jules Furthman, who penned Only Angels Have Wings (1939), where Furthman would recycle the theme of a disgraced professional confronting a festering yellow streak and eventual finding redemption through gruelling trials. Garnett isn’t half as interested in that theme as Hawks: Garnett, who like William Wellman had been a WW1 aviator, seems to empathise more with Gaskell as an unswerving professional who adjusts to any climate and eventually decides authenticity is preferable to elevation. Garnett was setting himself up at MGM as a reliable hand, talented at finding a median zone the proclivities of audiences feminine and masculine, able to step between Bataan (1943) and Mrs Parkington (1944) without blinking.

Garnett here looks forward to his own best-regarded work as director, The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), in studying the intersections of sexual desire and criminal temptation, and happily stokes his leads’ mutual heat, although the major key here is post-Depression insouciance, not post-War psychic dry rot. The macho business blends interestingly here with the feminine-social bitchery as China Doll finds herself looking like a misfire when confronted by Sybil and Yu-Lan’s skill at clay pigeon shooting, casually and coolly blasting their physical and rhetorical distractions.

The casting of the support roles cunningly tweaks some of the actors’ familiar types. Stone’s usual aura of gallant, practical integrity, apparent when he played Nayland Smith in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932) and later when he was Andy Hardy’s father, is effectively undercut as he plays a man desperate for redemption but quite exhausted by the spectacle of his own fetid anxiety: when he does finally recapture his nerve, and he’s confronted by the same cringing fear and ignobility in one of his former persecutors, he sets off to his agonising Calvary with an ever-so-slight curl of his lip in recognising irony. Beery plays another of his big, half-smart bullies, but revels in displaying the weird pathos under McArdle’s bluster.

Garnett constantly shifts camera angles and placements to shake up the familiar stand-and-talk syntax of early sound film, and pulls off some fine displays of technical and analytical filmmaking. There’s a great crane shot utilised twice in the film, laying bare the social and ethnic relations on the ship by starting with the Cantonese human cargo who ride on the open deck, creating little worlds for themselves in such unprotected space, and moving up to the multiracial mandarins of first class, barely noticing the grim business of survival for lower deck folk and the work of the dedicated folk who make their lives a breeze.

Action scenes, when they come, are strong if brief, particularly in a bloodcurdling storm sequence when a massive steamroller breaks loose on deck and careens over the top of unfortunate coolies, a tremendously well-staged episode that takes unseemly delight in the sight of crushed bodies. Gaskell snatches a young sailor from out of the way of the mechanical monster thanks to Garnett utilising a clever special effect, before nearly being knocked into the maelstrom himself, whilst Davids cowers in terror.

The climax, when McArdle’s plotting comes to a boil and the ship is boarded by pirates, is laced with memorable sadisms, as Davids has his shins splintered with rifle butts and Gaskell gets his foot crushed in a torture boot, rendering their climactic moves to battle the villains excruciating merely to watch. The awkward final note tries to satisfy the needs of both justice and romance, but Beery has a glorious soliloquy meditating upon his ardour for his unwitting assassin. It’s all corny stuff of course, pure pulp magazine fodder magnified not by pretensions like spiritual or symbolic dimensions like Strange Cargo (1940) or by auteurist fine-tuning a la Hawks and Ford’s many trips around similar latitudes, but by the sheer élan of the cast and filmmaking.