The Capture and Execution of Monmouth

The Monmouth Rebellion of 1685 ended in disaster at the Battle of Sedgemoor. But the story didn’t end there. Monmouth’s flight, capture, and eventual execution marked a dramatic and tragic conclusion to his ill-fated attempt to claim the English throne. This is the tale of his final days, filled with desperation, betrayal, and a gruesome execution that shocked the nation.

Monmouth’s Flight: A Desperate Escape

After the crushing defeat at Sedgemoor, Monmouth fled the battlefield. In the early hours of July 6, he discarded his armor and blue riband, symbols of his royal ambition. Accompanied by Lord Grey, his servant, his doctor, and a few loyal friends, Monmouth sought refuge among sympathizers.

They stopped at Chedzoy to change horses and then took the Bath road. Moving through the New Forest and Cranbourne Chase, Monmouth disguised himself as a shepherd to evade capture. At the Woodyates Inn, they released their horses and hid their bridles, hoping to disappear into the countryside.

The Hunt for Monmouth

The King’s forces were relentless in their pursuit. On July 7, Lord Lumley and his scouts captured Lord Grey and a New Forest guide at Holt Lodge. An elderly cottager, Amy Farrant, directed Lumley to a hedge where she had seen two men eating peas. This led to the discovery of Anthony Busse, one of Monmouth’s close companions.

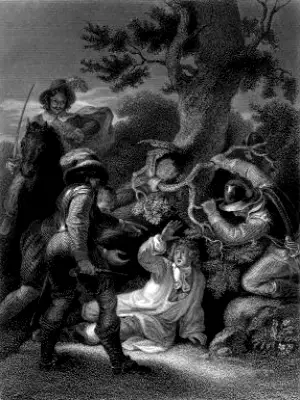

Busse revealed Monmouth’s hiding place in exchange for a possible pardon. On the morning of July 8, a militiaman named Henry Parkin found Monmouth hiding in a ditch, covered with ferns and brambles. Parkin reportedly burst into tears, regretting his role in the capture.

Monmouth’s Capture and Humiliation

Monmouth was exhausted and broken. He confessed he had not eaten a proper meal or slept peacefully since landing at Lyme Regis. Taken to Holt Lodge, he was handed over to the magistrate, Anthony Etterick, who ordered his transfer to London.

Over the next week, Monmouth was transported under heavy guard to the Tower of London. During this time, he wrote desperate letters to King James II, Queen Mary, and others, begging for mercy. His once-proud spirit was shattered.

When brought before the King, Monmouth fell to his knees, weeping and clutching his uncle’s legs. He invoked his father’s name, spread blame to others, and denied knowledge of the rebellion’s scale. Despite his pleas, the King remained unmoved.

The Trial and Sentencing

Monmouth’s crimes were too grave to pardon. He had declared war on the kingdom, killed the King’s men, and claimed the crown for himself. Such treason could not go unpunished.

Lord Grey, captured alongside Monmouth, faced the King with dignity. He admitted to the charges without begging for mercy, earning even the King’s respect. Both men were taken to the Tower of London through Traitor’s Gate, a symbolic entry for those condemned.

The Final Days

On July 13, Monmouth’s wife, Anne, visited him in the Tower. She brought the grim news that his execution was set for July 15. Monmouth received her coldly, more focused on seeking a pardon than comforting his family.

The night before his execution, Monmouth wrote more letters, pleading for his life. But his fate was sealed. On the morning of July 15, his wife and children bid him a tearful farewell. Monmouth, however, remained emotionless, resigned to his fate.

The Execution: A Gruesome Spectacle

At ten o’clock on July 15, 1685, Monmouth was taken to Tower Hill. A massive crowd gathered to witness the execution. Accompanied by bishops and clergymen, Monmouth mounted the scaffold with steady steps.

His first words were to the executioner, Jack Ketch:

“Is this the man to do the business? Do your work well.”

Monmouth then addressed the crowd, declaring,

“I shall say but very little: I come to die: I die a Protestant of the Church of England.”

The bishops interrupted, disputing his claim to the Church of England. Monmouth then spoke of his mistress, Lady Henrietta Wentworth, but the bishops condemned the relationship as sinful.

Monmouth handed Ketch six guineas, urging him to perform the execution cleanly. He referenced Ketch’s botched execution of Lord Russell in 1683, where multiple blows were needed.

Ketch’s performance was disastrous. His first blow barely nicked Monmouth’s neck. The second and third attempts failed to sever the head. Monmouth, still alive, glared at Ketch in reproach.

Finally, after two more blows and a knife, Monmouth’s head was severed. The crowd, horrified and enraged, threatened Ketch, who was quickly escorted away under guard.

Aftermath and Legacy

Monmouth’s head and body were placed in a coffin and buried under the altar of St Peter’s Chapel in the Tower. Rumors swirled that a substitute had been executed, and Monmouth lived imprisoned as the Man in the Iron Mask. These tales, though baseless, persisted for years.

The Monmouth Rebellion and its brutal aftermath left a lasting impact on England. The King’s retribution in the West Country was severe, with hundreds executed or transported as punishment.

Conclusion: A Tragic Chapter in History

Monmouth’s rebellion and execution mark a tragic chapter in English history. His ambition led to a bloody conflict and his own gruesome end. Yet, his story remains a powerful reminder of the consequences of treason and the fragility of power.

As we reflect on Monmouth’s fate, we are reminded of the human cost of political ambition and the enduring lessons of history.

Engage with History

Visit the Tower of London or the sites of the Monmouth Rebellion to connect with this fascinating period. Share Monmouth’s story to keep history alive for future generations.