Good Friday is a day of profound significance in Christian tradition, commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. But this solemn day is also entwined with other historical events that cast a shadow over its meaning, from lunar eclipses that may have marked Christ’s death to infamous assassinations and historical mysteries.

The First Good Friday and a ‘Moon of Blood’

According to the synoptic Gospels, the death of Jesus Christ was marked by darkness over the land. This event has long been thought to be a reference to an eclipse. A study by Professor Sir Colin Humphreys and W.G. Waddington suggests that the first Good Friday could be dated to April 3, 33 CE, based on a lunar eclipse. The phenomenon of a “moon of blood,” where the moon takes on a dark red hue, is believed to have been caused by atmospheric dust dispersing light, an effect noted by St. Peter in the Acts of the Apostles. This connection between the death of Christ and a cosmic event has fascinated historians and theologians alike, as it ties together celestial phenomena with earthly events.

Another Tragic Good Friday: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

Good Friday took on a new tragic significance in American history on April 14, 1865, when President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. Lincoln, accompanied by his wife and guests, was watching the play Our American Cousin when John Wilkes Booth, a famous actor and Confederate sympathizer, shot him in the head. Booth, who knew the play well, waited for a loud moment in the performance to fire his fatal shot, then escaped by leaping from the presidential box to the stage. Despite breaking his leg in the jump, Booth managed to flee the scene on a waiting horse.

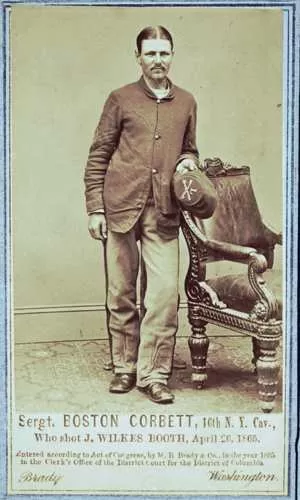

After his escape, Booth sought refuge at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd in southern Maryland, who set and bandaged his broken leg. Despite the attempt to evade capture, Booth’s luck ran out on April 26th at Garrett’s tobacco farm, where he was shot and killed by Union Sergeant ‘Boston’ Corbett. A reward of $100,000 was offered for Booth’s capture, with Conger receiving $15,000 for his efforts.

Boston Corbett: The Mad Hatter

Thomas “Boston” Corbett, the man who shot Booth, was an enigmatic figure. Born in London and raised in America, Corbett was a hatter by trade. The hat-making process of his era involved mercury, which often led to mercury poisoning—a condition that affected the brain and caused erratic behavior, giving rise to the phrase “mad as a hatter.” Corbett’s eccentricity went further than most; after losing his wife in childbirth, he castrated himself with scissors to avoid the temptation of prostitutes.

Corbett’s life after his military service was plagued by erratic behavior, and he was eventually committed to an insane asylum in Topeka, Kansas. After escaping, he lived in a hole in the ground in Concordia, Kansas, until his presumed death in the Great Hinckley Fire of 1894.

The Strange Case of Dr. Tumblety

David Herold, a co-conspirator of Booth, had worked for Dr. Francis Tumblety, a quack doctor who sold dubious medicines like “Dr. Morse’s Indian Root Pills.” Arrested for complicity in Lincoln’s assassination, Tumblety was eventually released without charge. However, his notoriety didn’t end there. In 1888, Tumblety was arrested in London for “gross indecency” and fled to America, where he fell under suspicion of being Jack the Ripper.

Dr. Tumblety had a reputation for misogyny, and his connections to London during the Ripper murders put him in the spotlight. However, most modern “Ripperologists” dismiss him as a serious suspect, despite his self-promotion and flamboyant lifestyle.

The Trial of Lincoln’s Assassins

After Booth’s death, his co-conspirators were arrested and brought to trial. On May 10, 1865, eight were charged with conspiracy, and on June 29, all were found guilty. Four—Mary Surratt, David Herold, Lewis Powell, and George Atzerodt—were hanged on July 7, 1865. The remaining conspirators, Samuel Mudd, Michael O’Laughlen, and Samuel Arnold, were sentenced to life imprisonment, while Edmund Spangler received a six-year sentence. O’Laughlen died of yellow fever in 1867, but Mudd’s medical efforts during the outbreak earned him a pardon, and he was released in 1869 along with Arnold and Spangler.

Misconceptions Around “Your Name is Mud”

The phrase “your name is mud” is often thought to be related to Dr. Samuel Mudd, who treated Booth after Lincoln’s assassination. However, this connection is false. The expression appeared in print as early as 1823, long before the assassination, and is unrelated to Dr. Mudd.

The Origins of “Assassin”

Another word with a murky history is “assassin.” It is commonly believed to derive from the Arabic “hashishiyyin,” meaning “hashish-users,” associated with the Nizari Ismaili Muslim sect during the Crusades. Under the leadership of Hasan ibn al-Sabbah, also known as the “Old Man of the Mountain,” these early assassins reportedly used hashish to transport themselves to a paradise-like state and were promised a return to this paradise if they obeyed their leader’s orders, which often involved assassination. However, some scholars argue the term comes from “asasiyun,” meaning “people faithful to the foundation of the faith,” while others believe it was used as a pejorative term for enemies or disreputable people.

Connecting the Dots: Good Friday’s Web of Mystery

What ties all these events together? From the crucifixion of Jesus to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the legends of assassins, Good Friday emerges as a day steeped in both religious reverence and historical mystery. Each story—from the celestial sign of a lunar eclipse marking Jesus’s death to Lincoln’s tragic end on Good Friday, 1865—reflects humanity’s enduring fascination with fate, faith, and the unpredictable twists of history.

This kaleidoscope of assassinations, rumors, and strange occurrences reminds us that history is as much about the stories we tell as it is about the facts. And whether it’s a “moon of blood” or the mystique of the word “assassin,” Good Friday has a way of intertwining itself with some of the most compelling narratives of our past.