After two and a half harrowing weeks at sea, the HMS Bounty, battered by squalls, heavy rain, and even a waterspout, finally approached Anamooka, an island familiar to Lieutenant William Bligh from his earlier visit with Captain Cook in 1777.

On April 23, 1789, the Bounty landed, and Bligh was eager to reconnect with the islanders. However, he was dismayed by the condition of the natives, many of whom bore sores and self-inflicted wounds from ritualistic mourning, including amputated fingers, even among small boys.

Despite the unsettling sights, the crew managed to procure supplies, including hogs, fowls, and yams, while also taking on fresh water and wood. However, during the process of filling the water casks, the sailors were surrounded by the islanders. In the ensuing chaos, tools were stolen, and stones were thrown at the crew. Fearing further violence, the work party retreated to the safety of the Bounty.

In a bid to recover a missing grapnail (a small anchor), Bligh threatened to detain some of the chiefs aboard the Bounty until it was returned. He had precedent for this approach; Cook had employed similar tactics during his visits. However, Bligh was not Cook. As the sun set, witnessing the chiefs weeping and beating their eyes with their fists, he relented, offering them gifts and allowing them to leave.

On April 27, the Bounty departed Anamooka, setting a northerly course for Tofua. Tensions flared among the crew over coconuts, with Bligh accusing some of theft, while the men denied the claims. This dispute, though not recorded in his official logs, hinted at the growing discontent among the crew. As was his custom every third evening, Bligh invited Fletcher Christian to dine with him, but Christian declined, citing indisposition.

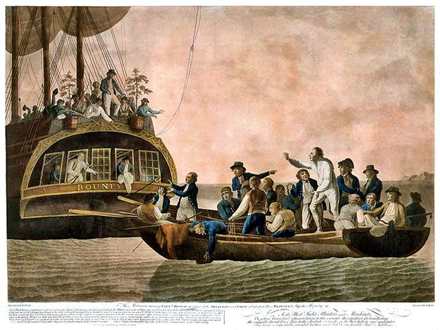

At 11 PM on April 28, Bligh went on deck to give orders to Fryer, the master, who was on watch. Shortly after midnight, a party of armed men, led by Christian, stormed Bligh’s quarters. He was dragged from his bed, tightly bound, and clad only in his nightshirt. As he cried out for help, he was met with threats to remain silent: “Hold your tongue, Sir, or you are dead this instant.”

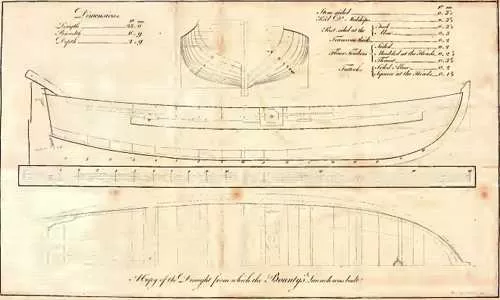

The crew quickly divided into factions—those loyal to Bligh and those following Christian. Tensions escalated, with cutlasses, muskets, and bayonets brandished. The mutineers attempted to put a smaller launch into the water, but it was found to be rotten. Instead, they launched the larger 23-foot boat, loading it with essential supplies: twine, canvas, sails, a compass, a quadrant, 150 pounds of bread, 32 pounds of pork, six quarts of rum, six bottles of wine, and 28 gallons of water—enough for about five days.

In a remarkable act of bravery, the clerk John Samuel managed to salvage Bligh’s logs, journals, and some ship’s papers. Bligh and eighteen loyal men were forced into the launch, while four others who wished to join were denied due to lack of space. As they were set adrift, Bligh’s calm assessment of the mutineers was astonishing, given the circumstances. He noted in his log, “I can only conjecture that they have ideally assured themselves of a more happy life among the Otaheitans than they could possibly have in England…”

Bligh speculated that the allure of the islands, combined with the charms of the local women, had led the crew to mutiny. He described the women as “handsome, mild in their manners and conversation,” and suggested that the chiefs had encouraged the sailors to stay, promising them large possessions. This insight into the motivations behind the mutiny highlights the complex interplay of desire, power, and survival.

Tofua lay ten leagues to the north, and Bligh raised the launch’s sail, catching a light breeze that carried them toward the island. However, due to steep cliffs, they were unable to land until the following day. Finding food and water proved challenging, and they made camp in a cave. Soon, they encountered some natives and traded what little they had for food. However, as more islanders arrived, the atmosphere grew increasingly hostile.

When about 200 islanders approached, banging stones together—a clear sign of aggression—Bligh calmly led his men back to the launch. Suddenly, the situation escalated as the islanders began hurling stones. With most of his crew aboard, Bligh attempted to cast off, but quartermaster John Norton was surrounded and brutally stoned to death. In a desperate bid to escape, Bligh cut the rope that tethered their launch to the shore, but a group of about twelve men in a canoe continued to attack.

Just when it seemed all hope was lost, Bligh began throwing clothing overboard. The islanders, distracted by the floating garments, paused to collect them, giving the launch a crucial opportunity to row away and escape into the open sea. The Friendly Islands were proving to be anything but friendly.

Bligh’s journey after the mutiny was fraught with peril, but his leadership and quick thinking saved the lives of those who remained loyal to him. The harrowing experiences of Bligh and his men highlight the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity. Their story is a testament to survival, courage, and the complexities of human relationships in the unforgiving environment of the Pacific Ocean. As they navigated the challenges ahead, the legacy of the Bounty mutiny would continue to resonate through history, reminding us of the thin line between civilization and chaos.