The war in the West in 1862 Military events, meanwhile, were transpiring in other arenas.

Table of contents

Trans-Mississippi theatre and Missouri

In the Trans-Mississippi theatre covetous Confederate eyes were cast on California, where ports for privateers could be seized, as could gold and silver to buttress a sagging treasury. Led by Henry Sibley, a Confederate force of some 2,600 invaded the Union’s Department of New Mexico, where the Federal commander, Edward Canby, had but 3,810 men to defend the entire vast territory. Although plagued by pneumonia and smallpox, Sibley bettered a Federal force on Feb. 21, 1862, at Valverde and captured Albuquerque and Santa Fe on March 23. But at the crucial engagement of La Glorieta Pass (known also as Apache Canyon, Johnson’s Ranch, or Pigeon’s Ranch) a few days later, Sibley was checked and lost most of his wagon train. He had to retreat into Texas, where he reached safety in April but with only 900 men and seven of 337 supply wagons left.

Farther eastward, in the more vital Mississippi valley, operations were unfolding as large and as important as those on the Atlantic seaboard. Missouri and Kentucky were key border states that Lincoln had to retain within the Union orbit. Commanders there–especially on the Federal side–had greater autonomy than those in Virginia. Affairs began inauspiciously for the Federals in Missouri when Union general Nathaniel Lyon’s 5,000 troops were defeated at Wilson’s Creek on Aug. 10, 1861, by a Confederate force of more than 10,000 under Sterling Price and Benjamin McCulloch, each side losing some 1,200 men. But the Federals under Samuel Curtis decisively set back a gray-clad army under Earl Van Dorn at Pea Ridge (Elkhorn Tavern), Ark., on March 7-8, 1862, saving Missouri for the Union and threatening Arkansas.

Operations in Kentucky and Tennessee

The Confederates to the east of Missouri had established a unified command under Albert Sidney Johnston, who manned, with only 40,000 men, a long line in Kentucky running from near Cumberland Gap on the east through Bowling Green, to Columbus on the Mississippi. Numerically superior Federal forces cracked this line in early 1862. First, George H. Thomas smashed Johnston’s right flank at Mill Springs (Somerset) on January 19. Then, in February, Grant, assisted by Federal gunboats commanded by Andrew H. Foote and acting under Halleck’s orders, ruptured the centre of the Southern line in Kentucky by capturing Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson, 11 miles (18 kilometers) to the east on the Cumberland River. The Confederates suffered more than 16,000 casualties at the latter stronghold–most of them taken prisoner–as against Federal losses of less than 3,000. Johnston’s left anchor fell when Pope seized New Madrid, Mo., and Island Number Ten in the Mississippi in March and April. This forced Johnston to withdraw his remnants quickly from Kentucky through Tennessee and to reorganize them for a counterstroke. This seemingly impossible task he performed splendidly.

The Confederate onslaught came at Shiloh, Tenn., near Pittsburg Landing, to which point on the west bank of the Tennessee River Grant and William T. Sherman had incautiously advanced. In a Herculean effort, Johnston had pulled his forces together and, with 40,000 men, suddenly struck a like number of unsuspecting Federals on April 6. Johnston hoped to crush Grant before the arrival of Don Carlos Buell’s 20,000 Federal troops, approaching from Nashville. A desperate combat ensued, with Confederate assaults driving the Unionists perilously close to the river. But at the height of success, Johnston was mortally wounded; the Southern attack then lost momentum, and Grant held on until reinforced by Buell. On the following day the Federals counterattacked and drove the Confederates, now under Beauregard, steadily from the field, forcing them to fall back to Corinth, in northern Mississippi. Grant’s victory cost him 13,047 casualties, compared to Southern losses of 10,694. Halleck then assumed personal command of the combined forces of Grant, Buell, and Pope and inched forward to Corinth, which the Confederates evacuated on May 30.

Beauregard, never popular with Davis, was superseded by Braxton Bragg, one of the president’s favorites. Bragg was an imaginative strategist and an effective drillmaster and organizer; but he was also a weak tactician and a martinet who was disliked by a number of his principal subordinates. Leaving 22,000 men in Mississippi under Price and Van Dorn, Bragg moved through Chattanooga with 30,000, hoping to reconquer Tennessee and carry the war into Kentucky. Some 18,000 other Confederate soldiers under Edmund Kirby Smith were at Knoxville. Buell led his Federal force northward to save Louisville and force Bragg to fight. Occupying Frankfort, Bragg failed to move promptly against Louisville. In the ensuing Battle of Perryville on October 8, Bragg, after an early advantage, was halted by Buell and impelled to fall back to a point south of Nashville. Meanwhile, the Federal general William S. Rosecrans had checked Price and Van Dorn at Iuka on September 19 and had repelled their attack on Corinth on October 3-4.

Buell–like McClellan a cautious, conservative, Democratic general–was slow in his pursuit of the retreating Confederates and, despite his success at Perryville, was relieved of his command by Lincoln on October 24. His successor, Rosecrans, was able to safeguard Nashville and then to move southeastward against Bragg’s army at Murfreesboro. He scored a partial success by bringing on the bloody Battle of Stones River (or Murfreesboro, Dec. 31, 1862-Jan. 2, 1863). Again, after first having the better of the combat, Bragg was finally contained and forced to retreat. Of some 41,400 men, Rosecrans lost 12,906, while Bragg suffered 11,739 casualties out of about 34,700 effectives. Although it was a strategic victory for Rosecrans, his army was so shaken that he felt unable to advance again for five months, despite the urgings of Lincoln and Halleck.

The war in the East in 1863

In the East, after both armies had spent the winter in camp, the arrival of the active 1863 campaign season was eagerly awaited–especially by Hooker. “Fighting Joe” had capably reorganized and refitted his army, the morale of which was high once again. This massive host numbered around 132,000–the largest formed during the war–and was termed by Hooker “the finest army on the planet.” It was opposed by Lee with about 62,000. Hooker decided to move most of his army up the Rappahannock, cross, and come in upon the Confederate rear at Fredericksburg, while John Sedgwick’s smaller force would press Lee in front.

Chancellorsville

Beginning his turning movement on April 27, 1863, Hooker masterfully swung around toward the west of the Confederate army. Thus far he had outmaneuvered Lee; but Hooker was astonished on May 1 when the Confederate commander suddenly moved the bulk of his army directly against him. “Fighting Joe” lost his nerve and pulled back to Chancellorsville in the Wilderness, where the superior Federal artillery could not be used effectively.

Lee followed up on May 2 by sending Jackson on a brilliant flanking movement against Hooker’s exposed right flank. Bursting like a thunderbolt upon Oliver O. Howard’s 11th Corps late in the afternoon, Jackson crushed this wing; while continuing his advance, however, Jackson was accidentally wounded by his own men and died of complications shortly thereafter. This helped stall the Confederate advance. Lee then resumed the attack on the morning of May 3 and slowly pushed Hooker back; the latter was wounded by Southern artillery fire. That afternoon Sedgwick drove Jubal Early’s Southerners from Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg, but Lee countermarched his weary troops, fell upon Sedgwick at Salem Church, and forced him back to the north bank of the Rappahannock. Lee then returned to Chancellorsville to resume the main engagement; but Hooker, though he had 37,000 fresh troops available, gave up the contest on May 5 and retreated across the river to his old position opposite Fredericksburg. The Federals suffered 17,278 casualties at Chancellorsville, while the Confederates lost 12,764.

Gettysburg

While both armies were licking their wounds and reorganizing, Hooker, Lincoln, and Halleck debated Union strategy. They were thus engaged when Lee launched his second invasion of the North on June 5, 1863. His advance elements moved down the Shenandoah valley toward Harpers Ferry, brushing aside small Federal forces near Winchester. Marching through Maryland into Pennsylvania, the Confederates reached Chambersburg and turned eastward. They occupied York and Carlisle and menaced Harrisburg. Meanwhile, the dashing Confederate cavalryman, J.E.B. (“Jeb”) Stuart, set off on a questionable ride around the Federal army and was unable to join Lee’s main army until the second day at Gettysburg.

Hooker–on unfriendly terms with Lincoln and especially Halleck–ably moved the Federal forces northward, keeping between Lee’s army and Washington. Reaching Frederick, Hooker requested that the nearly 10,000-man Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry be added to his field army. When Halleck refused, Hooker resigned his command and was succeeded by the steady George Gordon Meade, the commander of the 5th Corps. Meade was granted a greater degree of freedom of movement than Hooker had enjoyed, and he carefully felt his way northward, looking for the enemy.

Learning to his surprise on June 28 that the Federal army was north of the Potomac, Lee hastened to concentrate his far-flung legions. Hostile forces came together unexpectedly at the important crossroads town of Gettysburg, in southern Pennsylvania, bringing on the greatest battle ever fought in the Western Hemisphere. Attacking on July 1 from the west and north with 28,000 men, Confederate forces finally prevailed after nine hours of desperate fighting against 18,000 Federal soldiers under John F. Reynolds. When Reynolds was killed, Abner Doubleday ably handled the outnumbered Federal troops, and only the sheer weight of Confederate numbers forced him back through the streets of Gettysburg to strategic Cemetery Ridge south of town, where Meade assembled the rest of the army that night.

On the second day of battle Meade’s 93,000 troops were ensconced in a strong, fishhook-shaped defensive position, running northward from the Round Top hills along Cemetery Ridge and thence eastward to Culp’s Hill. Lee, with 75,000 troops, ordered Longstreet to attack the Federals diagonally from Little Round Top northward and Richard S. Ewell to assail Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill. The Confederate attack, coming in the late afternoon and evening, saw Longstreet capture the positions known as the Peach Orchard, Wheat Field, and Devil’s Den on the Federal left in furious fighting but fail to seize the vital Little Round Top. Ewell’s later assaults on Cemetery Hill were repulsed, and he could capture only a part of Culp’s Hill.

On the morning of the third day, Meade’s right wing drove the Confederates from the lower slopes of Culp’s Hill and checked Stuart’s cavalry sweep to the east of Gettysburg in mid-afternoon. Then, in what has been called the greatest infantry charge in American history, Lee–against Longstreet’s advice–hurled nearly 15,000 soldiers, under the immediate command of George E. Pickett, against the centre of Meade’s lines on Cemetery Ridge, following a fearful artillery duel of two hours. Despite heroic efforts, only several hundred Southerners temporarily cracked the Federal centre at the so-called High-Water Mark; the rest were shot down by Federal cannoneers and musketrymen, captured, or thrown back, suffering casualties of almost 60 percent. Meade felt unable to counterattack, and Lee conducted an adroit retreat into Virginia. The Confederates had lost 28,063 men at Gettysburg, the Federals, 23,049. After indecisive maneuvering and light actions in northern Virginia in the fall of 1863, the two armies went into winter quarters. Never again was Lee able to mount a full-scale invasion of the North with his entire army.

The war in the West in 1863

Arkansas and Vicksburg

In Arkansas, Federal troops under Frederick Steele moved upon the Confederates and defeated them at Prairie Grove, near Fayetteville, on Dec. 7, 1862–a victory that paved the way for Steele’s eventual capture of Little Rock the next September.

More importantly, Grant, back in good graces following his undistinguished performance at Shiloh, was authorized to move against the Confederate “Gibraltar of the West”–Vicksburg, Miss. This bastion was difficult to approach: Admiral David G. Farragut, Grant, and Sherman had failed to capture it in 1862. In the early months of 1863, in the so-called Bayou Expeditions, Grant was again frustrated in his efforts to get at Vicksburg from the north. Finally, escorted by Admiral David Dixon Porter’s gunboats, which ran the Confederate batteries at Vicksburg, Grant landed his army to the south at Bruinsburg on April 30, 1863, and pressed northeastward. He won small but sharp actions at Port Gibson, Raymond, and Jackson, while the circumspect Confederate defender of Vicksburg, John C. Pemberton, was unable to link up with a smaller Southern force under Joseph E. Johnston near Jackson.

Turning due westward toward the rear of Vicksburg’s defenses, Grant smashed Pemberton’s army at Champion’s Hill and the Big Black River and invested the fortress. During his 47-day siege, Grant eventually had an army of 71,000; Pemberton’s command numbered 31,000, of whom 18,500 were effectives. After a courageous stand, the outnumbered Confederates were forced to capitulate on July 4.Five days later, 6,000 Confederates yielded to Nathaniel P. Banks at Port Hudson, La., to the south of Vicksburg, and Lincoln could say, in relief, “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea.”

Chickamauga and Chattanooga

Meanwhile, 60,000 Federal soldiers under Rosecrans sought to move southeastward from central Tennessee against the important Confederate rail and industrial centre of Chattanooga, then held by Bragg with some 43,000 troops. In a series of brilliantly conceived movements, Rosecrans maneuvered Bragg out of Chattanooga without having to fight a battle. Bragg was then bolstered by troops from Longstreet’s veteran corps, sent swiftly by rail from Lee’s army in Virginia. With this reinforcement, Bragg turned on Rosecrans and, in a vicious two-day battle (September 19-20) at Chickamauga Creek, Ga., just southeast of Chattanooga, gained one of the few Confederate victories in the West. Bragg lost 18,454 of his 66,326 men; Rosecrans, 16,170 out of 53,919 engaged. Rosecrans fell back into Chattanooga, where he was almost encircled by Bragg.

But the Southern success was short-lived. Instead of pressing the siege of Chattanooga, Bragg unwisely sent Longstreet off in a futile attempt to capture Knoxville, then being held by Burnside. When Rosecrans showed signs of disintegration, Lincoln replaced him with Grant and strengthened the hard-pressed Federal army at Chattanooga by sending, by rail, the remnants of the Army of the Potomac’s 11th and 12th Corps, under Hooker’s command. Outnumbering Bragg now 56,359 to 46,165, Grant attacked on November 23-25, capturing Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, defeating Bragg’s army, and driving it southward toward Dalton, Ga. Grant sustained 5,824 casualties at Chattanooga and Bragg, 6,667. Confidence having been lost in Bragg by most of his top generals, Davis replaced him with Joseph E. Johnston. Both armies remained quiescent until the following spring.

The war in 1864-65

Finally dissatisfied with Halleck as general in chief and impressed with Grant’s victories, Lincoln appointed Grant to supersede Halleck and to assume the rank of lieutenant general, which Congress had re-created. Leaving Sherman in command in the West, Grant arrived in Washington on March 8, 1864. He was given largely a free hand in developing his grand strategy. He retained Meade in technical command of the Army of the Potomac but in effect assumed direct control by establishing his own headquarters with it. He sought to move this army against Lee in northern Virginia while Sherman marched against Johnston and Atlanta. Several lesser Federal armies were also to advance in May.

Grant’s overland campaign

Grant surged across the Rapidan and Rappahannock rivers on May 4, hoping to get through the tangled Wilderness before Lee could move. But the Confederate leader reacted instantly and, on May 5, attacked Grant from the west in the Battle of the Wilderness. Two days of bitter, indecisive combat ensued. Although Grant had 115,000 men available against Lee’s 62,000, he found both Federal flanks endangered. Moreover, Grant lost 17,666 soldiers compared to a probable Southern loss of about 8,000. Pulling away from the Wilderness battlefield, Grant tried to hasten southeastward to the crossroads point of Spotsylvania Court House, only to have the Confederates get there first. In savage action (May 8-19), including hand-to-hand fighting at the famous “Bloody Angle,” Grant, although gaining a little ground, was essentially thrown back. He had lost 18,399 men at Spotsylvania. Lee’s combined losses at the Wilderness and Spotsylvania were an estimated 17,250.

Again Grant withdrew, only to move forward in another series of attempts to get past Lee’s right flank; again, at the North Anna River and at the Totopotomoy Creek, he found Lee confronting him. Finally at Cold Harbor, just northeast of Richmond, Grant launched several heavy attacks, including a frontal, near-suicidal one on June 3, only to be repelled with grievous total losses of 12,737. Lee’s casualties are unknown but were much lighter.

Grant, with the vital rail centre of Petersburg–the southern key to Richmond–as his objective, made one final effort to swing around Lee’s right and finally outguessed his opponent and stole a march on him. But several blunders by Federal officers, swift action by Beauregard, and Lee’s belated though rapid reaction enabled the Confederates to hold Petersburg. Grant attacked on June 15 and 18, hoping to break through before Lee could consolidate the Confederate lines east of the city, but he was contained with 8,150 losses.

Unable to admit defeat but having failed to destroy Lee’s army and capture Richmond, Grant settled down to a nine-month active siege of Petersburg. The summer and fall of 1864 were highlighted by the Federal failure with a mine explosion under the gray lines at Petersburg on July 30, the near capture of Washington by the Confederate Jubal Early in July, and Early’s later setbacks in the Shenandoah valley at the hands of Philip H. Sheridan.

Sherman’s Georgia campaigns

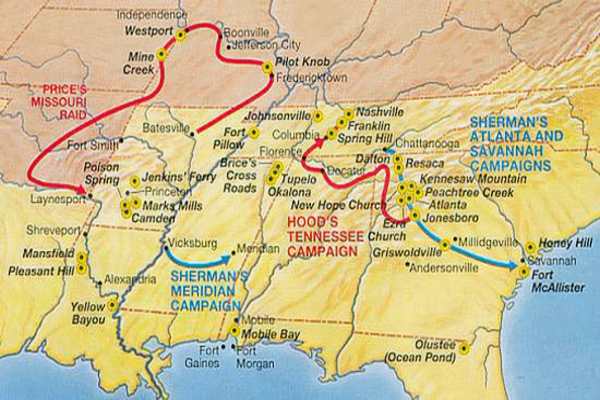

Meanwhile, Sherman was pushing off toward Atlanta from Dalton, Ga., on May 7, 1864, with 110,123 men against Johnston’s 55,000. This masterly campaign comprised a series of cat-and-mouse moves by the rival commanders. Nine successive defensive positions were taken up by Johnston. Trying to outguess his opponent, Sherman attempted to swing around the Confederate right flank twice and around the left flank the other times, but each time Johnston divined which way Sherman was moving and each time pulled back in time to thwart him. At one point Sherman’s patience snapped and he frontally assaulted the Southerners at Kennesaw Mountain on June 27; Johnston threw him back with heavy losses. All the while Sherman’s lines of communication in his rear were being menaced by audacious Confederate cavalry raids conducted by Nathan Bedford Forrest and Joseph Wheeler. Forrest administered a crushing defeat to Federal troops under Samuel D. Sturgis at Brice’s Cross Roads, Miss., on June 10. But these Confederate forays were more annoying than decisive, and Sherman pressed forward.

When Johnston finally informed Davis that he could not realistically hope to annihilate Sherman’s mighty army, the Confederate president replaced him with John B. Hood, who had already lost two limbs in the war. Hood inaugurated a series of premature offensive battles at Peachtree Creek, Atlanta, Ezra Church, and Jonesboro, but he was repulsed in each of them. With his communications threatened, Hood evacuated Atlanta on the night of August 31-September 1.Sherman pursued only at first. Then, on November 15, he commenced his great March to the Sea with more than 60,000 men, laying waste to the economic resources of Georgia in a 50-mile-wide swath of destruction. He captured Savannah on December 21.

Hood had sought unsuccessfully to lure Sherman out of Georgia and back into Tennessee by marching northwestward with nearly 40,000 men toward the key city of Nashville, the defense of which had been entrusted by Sherman to George H. Thomas. At Franklin, Hood was checked for a day with severe casualties by a Federal holding force under John M. Schofield. This helped Thomas to retain Nashville, where, on December 15-16, he delivered a crushing counterstroke against Hood’s besieging army, cutting it up so badly that it was of little use thereafter.

Western campaigns

Sherman’s force might have been larger and his Atlanta-Savannah Campaign consummated much sooner had not Lincoln approved the Red River Campaign in Louisiana led by Banks in the spring of 1864. Accompanied by Porter’s warships, Banks moved up the Red River with some 40,000 men. He had two objectives: to capture cotton and to defeat Southern forces under Kirby Smith and Richard Taylor. Not only did he fail to net much cotton but he was also checked with loss on April 8 at Sabine Cross Roads and forced to retreat. Porter lost several gunboats, and the campaign amounted to a costly debacle.

That fall Kirby Smith ordered the reconquest of Missouri. Sterling Price’s Confederate army advanced on a broad front into Missouri but was set back temporarily by Thomas Ewing at Pilot Knob on September 27. Resuming the advance toward St. Louis, Price was forced westward along the south bank of the Missouri River by pursuing Federal troops under A.J. Smith, Alfred Pleasonton, and Samuel Curtis. Finally, on October 23, at Westport, near Kansas City, Price was decisively defeated and forced to retreat along a circuitous route, arriving back in Arkansas on December 2. This ill-fated raid cost Price most of his artillery as well as the greater part of his army, which numbered about 12,000.

Sherman’s Carolina campaigns

On Jan. 10, 1865, with Tennessee and Georgia now securely in Federal hands, Sherman’s 60,000-man force began to march northward into the Carolinas. It was only lightly opposed by much smaller Confederate forces. Sherman captured Columbia on February 17 and compelled the Confederates to evacuate Charleston (including Fort Sumter). When Lee was finally named Confederate general in chief, he promptly reinstated Johnston as commander of the small forces striving to oppose the Federal advance. Nonetheless, Sherman captured Fayetteville, N.C., on March 11 and, after an initial setback, repulsed the counterattacking Johnston at Bentonville on March 19-20. Goldsboro fell to the Federals on March 23, and Raleigh on April 13. Finally, perceiving that he no longer had any reasonable chance of containing the relentless Federal advance, Johnston surrendered to Sherman at the Bennett House near Durham Station on April 18. When Sherman’s generous terms proved unacceptable to Secretary of War Stanton (Lincoln had been assassinated on April 14), the former submitted new terms that Johnston signed on April 26.

The final land operations

Grant and Meade were continuing their siege of Petersburg and Richmond early in 1865. For months the Federals had been lengthening their left (southern) flank while operating against several important railroads supplying the two Confederate cities. This stretched Lee’s dwindling forces very thin. The Southern leader briefly threatened to break the siege when he attacked and captured Fort Stedman on March 25. But an immediate Federal counterattack regained the strongpoint, and Lee, when his lines were subsequently pierced, evacuated both Petersburg and Richmond on the night of April 2-3.

An 88-mile (142-kilometre) pursuit west-southwestward along the Appomattox River ensued, with Grant and Meade straining every nerve to bring Lee to bay. The Confederates were detained at Amelia Court House, awaiting delayed food supplies, and were badly cut up at Five Forks and Sayler’s Creek, with their only avenue of escape now cut off by Sheridan and George A. Custer. When Lee’s final attempt to break out failed, he surrendered the remnants of his gallant Army of Northern Virginia at the McLean house at Appomattox Court House on April 9. The lamp of magnanimity was reflected in Grant’s unselfish terms.

On the periphery of the Confederacy, 43,000 gray-clad soldiers in Louisiana under Kirby Smith surrendered to Canby on May 26. The port of Galveston, Tex., yielded to the Federals on June 2, and the greatest war on American soil was over.

American Civil War: (1861 – 1865) Part 1

American Civil War: Part 2, Eastern Campaigns, 1861-65

American Civil War: Part 4, The Naval War