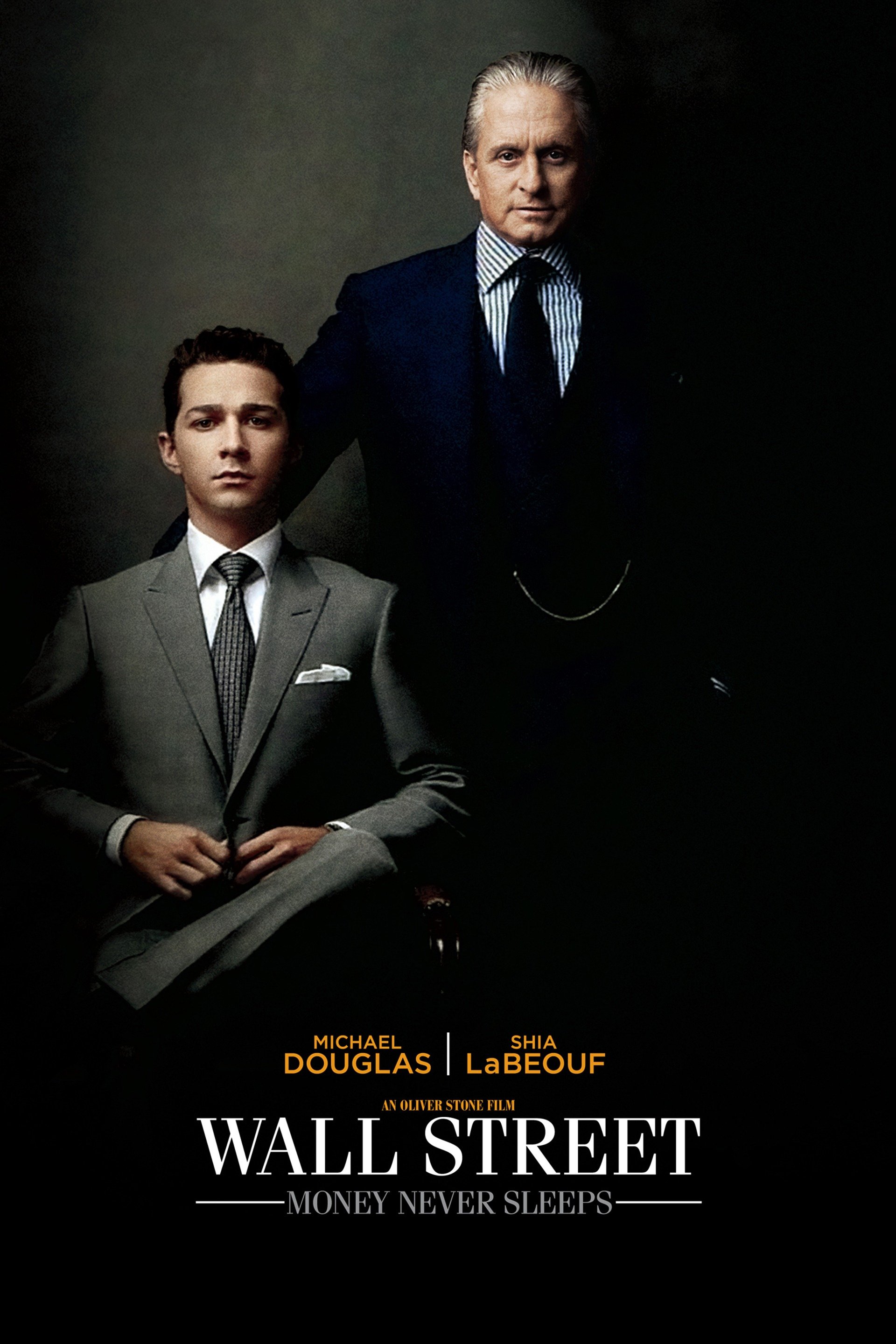

Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010) Movie

Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps sports a marvellous performance by a suavely aging movie star playing a tycoon who’s both avuncular yet subtly seedy and corrupt.

That performance is by Eli Wallach, who, at age 95, walks off with this film under his arm in his small but eye-catching role as Julie Steinhardt, senior partner in business to the film’s chief villain Bretton James whose unique battle cry is one of whistling like a bird whenever he’s sealed an irrevocable deal, be it assassinating business partners and rivals, or signing on with new ones. Oh yes, and Michael Douglas returns to his Oscar-winning role as Gordon Gekko.

I don’t really mean disrespect to Douglas, who essays the role with authority and a supple, if not exactly subtle, mix of the Machiavellian, the grasping, and the emotionally wearied. But how his performance impacted upon me is far more bound up in how well the film and its screenplay work, in spite of the fact that Douglas grasps the character with an intuitive sympathy well beyond what the filmmakers can wield.

Oliver Stone returns here both to the laurels of past movie hits and the integral storytelling of his ‘80s work, as opposed to his grandiose, sprawling pseudo-experimental ‘90s and early ‘00s films, in offering another melodrama that also offers a panorama of financial culture in 2008. As Gekko once embodied the rampant spirit of greed in Stone’s 1987 original, here he’s something more of an anti-hero, both attempting to leverage a comeback by any means necessary, but also a figure of astuteness who both predicts the Global Financial Crisis and knows how to make great wads of money during its darkest days.

Reviving a figure like Gekko for such a purpose is both apt and also incidentally places him in the company of the predators, terminators, Hannibal Lecter and Indiana Jones, except he’s a franchise figure from a more “serious” type of moviemaking.

The fact that Douglas’s young co-star Shia LaBeouf comes straight off Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull exacerbates the likeness. It’s not, however, a bad idea, at least in theory, and the desire to see how time has changed Gekko, or if it’s changed him at all, is initially the film’s biggest attraction.

Bravely, however, Stone and screenwriters Allan Loeb and Stephen Schiff keep Gekko off-screen for the film’s first act, except for a brief opening scene when he’s being released from prison. Warning bells about what will follow are rung when Stone cues a cute laugh at the huge size of the ‘80s-model mobile phone he took to jail with him, except that subsequent revelations about when he actually went to prison, in the ‘90s, reveal this as a cheap and anachronistic joke.

Nonetheless, the film’s first third is surprisingly engaging as it lays out the stakes of a more contemporary drama. Gekko’s grown daughter Winnie (Carey Mulligan, in full winsome waif mode) now runs a left-leaning journalism website, and is shacked up with young stockbroker Jake Moore (Shia LaBeouf). Jake has an idealistic interest in green technology, and is working to secure funding for a fusion reactor development, but he actually works for Louis Zabel (Frank Langella), an investment banker who finds his company under assault from rumours of toxic debt and hollowed assets.

Jake and Louis have a strong, practically familial relationship, Louis having helped get Jake through college and taken him under his wing since meeting him as a teenaged caddy. Zabel is driven to the wall in an excruciating sweetheart bailout by Bretton James (Josh Brolin, returning to work with Stone after doing right by him in W.), and realises the whole deal was somehow concocted by James as revenge for a long-ago clash. Zabel, after selling out to James for a humiliating share price, throws himself in front of a train.

“No-one else in these markets had the balls to commit suicide, it’s an honorable thing to do,” Gekko pronounces, when he meets Jake, in assessment of Zabel’s fate. Jake comes to listen to Gekko give a lecture at his old alma mater, Gekko having reinvented himself as a writer and guru predicting inevitable meltdown.

But Gekko is still angling for a way to get back on top, humiliated by financial titans who don’t recognise him and harbouring his own grudge against James, whose testimony sent him to prison for a much longer stretch than his finagling in the original film would have earned him. Jake is intrigued by Gekko both as a potential new father figure and as a willing partner in vengeance on James.

He agrees to help Gekko get back in touch with Winnie, who bears deep emotional scars from her father’s imprisonment and venal behaviour, which she blames for her mother’s suicide and her junkie brother’s death. There is a stake behind Gordon’s interest in reuniting with Winnie, as well as an emotional imperative: she controls, unbeknownst to Jake, a $100 million fund in a Swiss bank which her father set up in her name before his jail time. Conniving ensues.

Whilst Stone resists the overt fragmentation of narrative and vision essayed in his most ambitious films, his familiar ability to set multiple story strands and explore a milieu on both a micro and macrocosmic level is still on display, through montages, cunning reproductions of real-life events, and visual aids that range from the witty (superimposed trading graphs that skip and trace the skylines of cities) to the hammy (recurring metaphors like falling dominoes and drifting bubbles).

This helps get Money Never Sleeps off to a rocketing start. The new subtitle is a paraphrase, for Gekko describes money as “a bitch that never sleeps”, which is rather punchier but understandably not friendly to movie marketing. Stone’s auteurist fondness for stories that pit good and bad mentors at odds in guiding his naïve heroes is reconfigured into the trinity of Zabel, James, and Gekko between them as a newly ambiguous figure, evoking Al Pacino’s similarly haggard but still determined coach in Any Given Sunday (1999). James, played by Brolin with the beautiful cool and lazily cocked eyes of a lion who’s just eaten but is eyeing his next meal, keeps a draft version of Goya’s “Saturn Eating His Son” in his study.

He challenges Jake not only to take a job with him when he learns of a scam Jake pulled to get some payback on James, but also to a motorbike duel which evokes, just faintly, the chariot battle of Boyd and Plummer in The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). And empires are shaking, if not all falling, as James has to talk the Federal Reserve honcho (Jason Clarke) into the colossal bailout with the words – yes – “We’re too big to fail.”

A cameo by Charlie Sheen as Bud Fox, the hero of the first film, has a sly quality in letting him appear as, well, Charlie Sheen, and performs an amusing rewrite of the priorities of the progenitor: whilst Gordon has remained hungry and interesting, Fox, having become rich rebuilding his father’s airline, has grown into a plump, smarmy playboy in a bubble of hedonism and “philanthropy”. This is actually the film’s most original touch, presenting the main protagonist of the earlier drama as having grown less than the villain.

But Stone’s familiar weaknesses dog him as well. The screenplay, which in the first third of the film sets a number of elements in play with care, runs out of ideas with stunning rapidity, and the basic flatness and contrived quality of the characters and story becomes increasingly obvious. The key to Stone’s breakthrough with his early films like Platoon (1986), Wall Street itself, and JFK (1991), was his learning to reduce complex processes and crises to emblematic conflicts and dramatic personae that could be grasped by just about anyone. But this reductive sensibility has consistently sabotaged him and his attempts to be taken seriously as America’s foremost cinema intellectual.

Even that illustrative capacity seems to have failed him here, for in spite of Brolin’s fine playing and the traits mentioned above, Bretton James never even momentarily gains the sort of self-animating life Gekko retains. Signifiers of power and evil collect about James, rather than him seeming to attract them. His comeuppance is rushed and flimsy on both the plot and dramatic levels, hinging on a particularly high-speed version of the old “write the story, win the war” crusading journalist motif.

Jake gets over his uncertainty whether or not to zap James and risk his own Wall Street future sees him hand all of the details about shady deals, which he and Gekko have uncovered without even a decent investigative montage, over to Winnie to publish on her site. The complexity of both collecting such information and disseminating it with effect to result in a tycoon’s downfall is dismissed as mere business for some other movie.

Where it needed the unpredictable ingenuity of Scorsese’s The Color of Money (1986) for reviving and exploring an iconic character’s redemption, Money Never Sleeps becomes increasingly flat and predictable as it proceeds, even having the gall to pass off the fact Gekko is manipulating Jake and angling to get hold of the money as a momentous twist worthy of flashbacks to telling moments, a la The Sixth Sense and Fight Club. What the hell else would Gordon Gekko be doing other than fucking someone over? That’s like trying to pass off Godzilla stomping on Tokyo as a surprise ending.

The attempt to marry the main drama to the financial crisis is oddly ineffectual, in large part because the fates of both Gekko and James are divorced from the crisis itself: James weathers the storm after conveniently being presented as the one who argues for saving big banking by the government, and Gekko’s canny enough to know how to beat it entirely. A subplot involving Jake’s efforts to prop up his mother’s (Susan Sarandon) real estate chicanery which falls prey to the credit crunch is more to the point, but Sarandon’s diva overacting and the cheap convenience in how this strand is introduced and played out nullifies its relevance.

Virtually nothing that happens in the final third is believable, and this taint is all too clearly observable in the young heroes. Jake, with his mixture of gullibility and ethical-investor cool, is committed to a scheme that is way over the top as far as movie dreamer projects go, and his stunning idiocy in handing over $100 million to a convicted felon and then getting huffy when he doesn’t do exactly what he said he would defies belief. Likewise, Winnie, with her righteousness, planning to casually give away said millions to charity, and treating her father like a leper to avenge her dead brother, is, in spite of Mulligan’s admirable playing of deep emotional trauma and I-learned-the-hard-way wisdom, still never feels like anything but a screenwriter’s convenient embodiment of everything noble and victimised. Winnie and Jake’s bust-up merely reminded me of how irritated I am by scenes in modern movies where weak-willed guys prostrate themselves before pitilessly judgmental women, which play out by rote.

Given that the original Wall Street gave itself away as a cheesy morality play masquerading as an intense contemporary drama, especially in the finale’s glimpse of Fox climbing the stairway to grace via the judicial system, it’s no surprise the sequel should follow in its footsteps. But the sententious thematic roll-out of Money Never Sleeps never comes close to the original’s earned zeitgeist impact, coming a distant second even to a film as glib as The Social Network in that regard.

The later twists and turns of the story are execrably handled. Gekko’s resurgence as a kingpin thanks to the pilfered money, jamming huge stogies in his mouth and leaning back with satisfied gall, is bad enough, and that’s before we have Jake shaming him with womb shots of his unborn grandson. What a tawdry place for a film with such collaborators to end up, especially after the fine scene when Winnie and Gordon partly reconcile, both revealing their pain with an actor concision that surprisingly resists bathos, the duo each retaining some nobility in their separate, equal agony.

The notion that just like the shark he acts like, Gordon needs to keep moving or be suffocated by shame and grief is mooted, but then sidestepped. The whole film has a tone common to so much of Stone’s recent output, as if the project had not been brought far enough along in the per-production and what was finally assembled on screen is a misbegotten, pared-down version of the original intention. The final, intolerably sloppy reconciliation scenes merely underline the complete failure of imagination and inspiration.