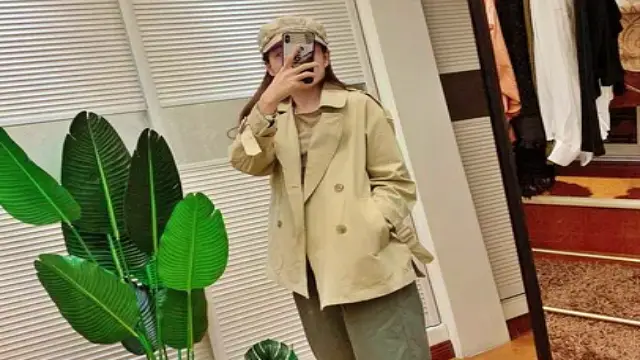

Faraz Ansari, Shabana Azmi, Swara Bhasker and Divya Dutta (rear row) meet Haima Simoes and Shruti Venkatesh. Location Courtesy/The Latit. Pic/Ashish Rane

Swara Bhasker, Divya Dutta, Shabana Azmi and the maker of their characters meet a female queer couple to see if the L in LGBTQi is getting enough screen time

Anju Maskeri (MID-DAY; October 13, 2019)

In 2017, Faraz Ansari released the 20-minute silent film, Sisak. Mostly self- funded and partially crowdfunded, it told the story of unspoken love between two men who travel on a Mumbai local. The film won awards at 44 film festivals.

Two years later, Mumbai-based Ansari is back with Sheer Qorma starring Swara Bhasker and Divya Dutta, women in love with each other, and Shabana Azmi as Bhasker’s mother.

Bhasker and Dutta agree to meet for a chat with Haima Simoes and Shruti Venkatesh, a young lesbian couple from Mumbai. The women work as programme coordinators for One Future Collective, a feminist youth led not-for-profit organisation that works on building compassionate youth social leadership in India, and are occasional models.

Edited excerpts from a freewheeling conversation on what it means to be gay in India after 377 was decriminalized, and how realistically straight characters can play queer on screen.

Making women count

Faraz: When I travelled with Sisak to over 150 film festivals, I realised that patriarchy exists within the queer community too. I met a Pakistani lady, who felt the protagonists in my film could have been women. The only reason I hadn’t chosen women was because I wouldn’t have managed permissions to shoot inside the ladies’ compartment. But, her words stayed with me. Among the queer section, women of colour are the most underrepresented. As a filmmaker, I enjoy a certain privilege and there was little point if I didn’t use it.

Swara: The day the Sheer Qorma trailer released, an assistant director I’ve worked in the past, gushed how happy she was that I was playing a gay character. She is lesbian and has been trying to get her parents to come around. Her family has dismissed her choice and wants her to get therapy. She asked if she could work on the film, because if she was part of the crew, her family would at least watch it. I realised how powerful film can be for social change.

Shabana: Yes. I play a parent who has reservations about her daughter’s sexual orientation, and for me to say, ‘yeh kudrat ke khilaf hai’ is something I don’t believe in. I’m saying exactly the opposite of what I, Shabana, believes. But the character graph was so very important that it’s a story that had to be told. A couple of years ago, I did this American film, Signature Move, which was screened at Tribeca. I played a mother who moves into her daughter’s home after her husband has passed away and spends all her time through looking through binoculars at prospective husbands for her daughter. Later, not only do I realise that she is gay, but that she is also a lucha libre wrestler. That was more comedy; this is much more emotional.

Mumbai the LGBTQi mecca

Shabana: Deepa Mehta’s Fire released in 1997. Since then, there’s so much more discussion on queer subjects, and not just in films. If you decided to make a queer film now, you’ll have a safer passage than you did then.

Faraz: I remember watching Fire at Regal Cinema. I was underage but had managed to get access because my dad somebody who worked at the theatre. I was so moved and happy to learn that there are more people like myself in this world. Before that, nobody had attempted a true representation of same-sex relationships in Indian cinema.

Haima: Being queer is much easier in Mumbai than in other [Indian] cities. Shruti and I met each other in college. The non-judgmental, liberal atmosphere on campus helped our relationship blossom. The fact that the college was accepting and full of strong feminist women— we even had a queer professor— helped us come to terms with our sexuality.

Shruti: It was so liberal that that you’d have to be closeted if you were homophobic, in fact!

Shabana: What you just said is significant. This is true transformation.

Shruti: But when you move from a safe space such as that one into society, you feel at sea. That’s when you feel the discrimination. Although we live together now, renting an apartment is always difficult. There’s prejudice everywhere. For instance, I have stopped going to gynecologists. There are always uncomfortable questions asked regarding your sexuality that are far from relevant to the issue. Similarly, trans people have it much worse when it comes to healthcare.

Haima: Bathroom signages depicting skirt and pants to differentiate men and women can be quite stressful for trans and non binary people. Every time I step inside the ladies restroom, I get the stares just because I don’t fit into the accepted idea of a woman.

Love is love

Swara: I’ve never played a gay character, and so, while I did wonder if I should speak to a gay person before filming, I later asked myself if I would have done it before playing a heterosexual. I decided against it. I don’t know if that was right but I wanted to discover the character within me.

Divya: I think acting is all about reacting. When I am playing the role of Saira, I think the idea is to find the complexes and vulnerability within you. Love is love, whether you are queer or straight.

Shruti: As the audience, I am more importantly looking for the right treatment of the character. What I want to see is a realistic portrayal minus the caricature.

Faraz: I’ve made a family film, but I’ve also not shied away from giving room to intimacy, because it supported the narrative. But the reason I chose to name it after a dish is because food is a metaphor. When I came out to my mother at 21, she did not speak to me for six months. And when she eventually did, she decided to make it up by preparing biryani. Food can unite.

Love is love, whether you are queer or straight – Divya Dutta