n

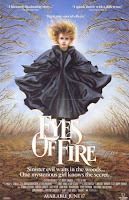

nOther people talk about movies that shaped them as children with a nostalgia-laced glee. Unfortunately, I didn’t really watch movies as a child. Oh, sure. I saw one or two a year, but they didn’t really make that much of a lasting impression on me. Now, you might be thinking to yourself: If you didn’t watch movies as a child, what did you do instead? Um, duh. I was out frolicking in the woods. What were you doing? Which brings me to the amazing, the one of a kind, the wonderfully lush and the creepy as all get out, Eyes of Fire. A movie that not only scratched the living fuck out of at least seven of my primary itches, it managed to reinvigorate my love of the forest. (Wait. I thought you despised nature?) Nah, I love nature. Granted, I’m not a big fan of jungles. But that’s mostly to do with my dislike of dank, humid weather and khaki-coloured clothing. Anyway, even though I’m drawn to the city, the forest is where I’m most comfortable. Which, in a way, explains why Avery Crounse‘s sinister ode to devils, ghosts, magic, fairies and witchcraft is the first film to remind me of my childhood in a long time. In fact, you could view it as an eerily accurate documentation of my early days growing up in the wilds of suburbia. You see, whereas most suburbs are simply a collection of bland subdivisions, mine was surrounded by a glacial ravine that formed after the last Ice Age. Isn’t that rad? Well, I think it is.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nEnough about my childhood. You know why so many prayers go unanswered in North America? That’s because their religion probably doesn’t work here. In order to make your particular brand of voodoo function properly, you need to practice it in the place it originated. For example, if your belief system was founded in, oh, let’s say, the Middle East, you’re going to have a better chance of getting it to work over there.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nIt’s true, I first got wind of this theory from a mentally-ill man who used to scream at shoppers near Yonge and Dundas in Toronto, Ontario. Nevertheless, I think this nut-job was onto something, because the Christian characters in Eyes of Fire come face-to-face with “The Great Spirit” of The Shawnee and things don’t exactly go their way.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nIt should be noted, however, that the pious characters have an Irish faerie in their midst. Meaning, her voodoo originated in Ireland. Which, as most of you know, is closer to North America than the Holy land. You see what I’m getting at? The shock-haired Leah, “Queen of the Forest” (Karlene Crocket), has a better chance of defeating the devil witches that populate the pristine woodlands of 1750’s America than Will Smythe (Dennis Lipscomb) and his puffy-shirted brand of Christendom.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nOf course, I’m not saying that every forest in 1750’s America was crawling with devil witches, and, not to mention, deformed tree people. It just so happens that the forest that Will Smythe and his wives and children decide to call their promise land is home to the spirits of the dead.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nEverything that enters this deceptively serene valley is eventually absorbed by the forest. If you look closely, you can see human faces peppered across the trunks of the trees in the early going. Or, at least, I saw faces. Don’t forget, I spent the bulk of my childhood inside an ancient glacial ravine. In other words, I some times have trouble distinguishing trees from people and vice-versa.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nThe Shawnee, despite the intrusive nature of the settlers, try to warn outsiders by draping the entrance to the valley with white feathers. But Will Smythe dismisses it as Native American poppycock, and continues on his merry way. Come to think of it, I think the feathers were put there to warn other Shawnee, not wayward white people. Either way, Will Smythe ignores the warning.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nQuirky fun-fact: Most European settlers during this period didn’t view themselves as intruders, but as pioneers.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nStumbling upon the ruins of a previous settlement, the pompous preacher/polygamist declares it to be their new home.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nShocked to discover that his wife and daughter have fled into the wilderness with a perverted preacher, Marion Dalton (Guy Boyd), a rugged frontiersman, catches up with them just they’re about to put down roots in the valley.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nWhile Leah and Marion (who is quite knowledgeable when it comes to Shawnee folklore) are keenly aware of the evil that surrounds them, Will Smythe and his followers remain blissfully ignorant to the danger. The big question being: Will Marion be able to convince his wife and daughter that this Will Smythe guy is a fraud in time before the forest absorbs their souls? Probably. I mean, I hope so.

n

n

n

n

n

n

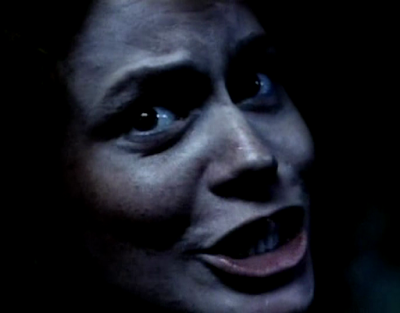

nNonetheless, the foreboding atmosphere the film manages to maintain throughout its spry running time is the film’s strong suit (we only get brief shots of the ghosts at first). The film’s unique (Ken Russell-esque) special effects are also an important factor, as they add an almost surreal element to the proceedings.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nAs expected, out of all the characters, I related to Leah and her pale knees the most. Call me crazy, but the shots of her acting weird and slightly demented in the woods were like looking directly into a mirror (minus, of course, the 1700s nightshirt and large mane of curly red hair).

n

n

n

n

n

n

nI don’t know if I still have this ability, but there once was a time when I could hear the trees talking to one another. I’m almost tempted to revisit the glacial ravine of my not even close to being misspent youth to see if I still possess this power. What I think I’m trying to say is, I miss the woods. And Eyes of Fire managed to rekindle my desire to lose myself within its verdant splendour.

n

n

n

n

n

n

nOh, and to my surprise, the film isn’t Canadian. Believe it or not, it’s American (shot in Missouri). Nonetheless, it has this strange Canuck vibe about it.