nn

n

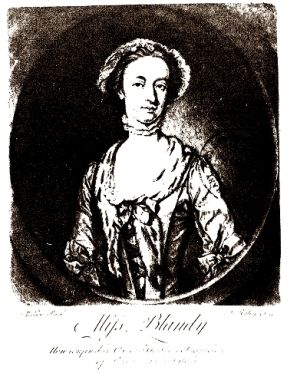

n Miss Mary Blandy received just the sort of educationnsuited to an eighteenth century, middle-class lady, furnishing her with all thenrefinements, graces and accomplishments society required in one of her station.nShe was the only daughter of Mr Francis Blandy, a town clerk and attorney ofnHenley-on-Thames, a dour, sharp-witted, social climber whose profession broughtnhim into the acquaintance of those very people he sought to emulate. Whether itnwas true or not, Mr Blandy let it be known thereabouts that he had settled andowry of ten thousand pounds on his daughter, something which, inexplicably,nsuddenly made her quite an attractive prospect to the young men of the HomenCounties.

n

n

n

|

| Miss Mary Blandy |

n

n

n

nAlthough she was comely and educated, Miss Blandy bore the marks ofnsmallpox on her ordinary face, and she had reached the age of twenty-five yearsnwithout yet walking down an aisle. Her father and mother had instilled a strongnmercenary caution in her, although it was rumoured that she had developed annoverly strong predilection for the military officers stationed in Henley andnthere were no objections raised when she became betrothed to a captain there,nalthough the prospect of this union faded when he was posted away on servicenoverseas.

n

n

n

|

| Miss Blandy and Captain Cranstoun |

n

n

n

nThen, in 1746, fate brought another suitor into her life, anlieutenant of marines, one Honourable William Henry Cranstoun, the fifth son ofnthe Scottish baron, Lord Cranstoun, and although Miss Blandy blew somewhat coldnin the beginning, she was encouraged by her father, a regular diner with Cranstoun’snuncle, General Lord Mark Kerr, who had bought his nephew’s commission in thenarmy for him. So, for Mary, it was off with the old love and on with the new,nher head turned by Cranstoun’s boasts that he was related to at least half ofnthe royalty or nobility of Scotland.

n

n

n

nFriends of the Blandy’s were astonishednwhen the old lawyer began babbling about ‘my Lord of Crailing’, and hisnwife tattled with her gossips about ‘Lady Cranstoun, my daughter’s new mamma’.nThe prospect of a title blinded the Blandys, and they seem tonhave wilfully ignored the fact that Cranstoun was merely the fifth son of anfinancially embarrassed baron. That, and he was forty-six years old,npockmarked, weedy, weak-eyed, bandy and very nearly a dwarf.

n

n

n

|

| Miss Mary Blandy |

n

n

n

nThese inconveniencesnbecame mere irrelevancies, however, when Lord Kerr, concerned for his lawyernfriend and his daughter, wrote a letter to them revealing that his nephew wasnalready married and was the father of an infant daughter. Cranstoun was alreadynahead of the game; he had already intimated to Mary that he was involved in anlawsuit with a Scottish woman who claimed, illegally, that she was his wife.

n

n

n

nInnthe mean time, he had written to his wife (who was ignorant of what was goingnon in Henley), explaining that his only hope of gaining a valuable promotionnwas to convince his superiors that he was a single man, and asking her to writento him, using her maiden name, and clearing up this inconvenientnbeing-married-to-her rumour. When her letter arrived, he had copies made andncirculated, which eventually brought him into the courts, where the validity ofnhis marriage was legally confirmed, when his original letter to his wifenoutlining his devious scheme was revealed, and he was ordered to provide annannuity of forty pounds for his wife and a further ten pounds for the daughter.

n

n

n

nCranstoun’s fortunes faded further when, after the Treacy of Aix-la-Chapellenwhich ended the War of the Austrian Succession in 1748, his regiment wasndisbanded and he was placed on half pay. Mrs Blandy’s cherished dreams ofnchatter with her noble in-laws over the tea-cups in the parlour of Crailingnwere slowly withering away and when she passed away soon after, the scalesnseemed to fall from his grieving husband’s eyes. He banned his daughter from anynfurther dealings with the disgraced Cranstoun, but she, blinded by hisnflatteries, could only see the errors in the words of those who spoke againstnhim and secretly continued the affair. By now she was past thirty, thenindignity of spinsterhood was now a distinct possibility and it would only takena stroke of a pen by her increasingly grouchy father to deny her the tennthousand pounds.

n

n

n

|

| Park Place |

n

n

n

nCranstoun met her secretly at Park Place, their normalntrysting-place, before he left Henley for the last time, and he promised tonsend her a love philtre which, when introduced into her father’s food, wouldncause him to change his mind and sanction their union. This powder, he toldnher, would be labelled, ‘Powder, to clean the Scottish Pebbles’,nScottish pebbles being greatly in fashion as jewellery at the time. Early inn1751, a box of table linen and Scottish pebbles arrived at the house in Henley,nfollowed some weeks later by another. During the year, the old lawyer’s healthnbecame worse and worse, his clothes hung from his withering limbs, his teethnbegan to fall from his gums, and his ill temper grew.

n

n

n

nHe quarrelled constantlynwith his daughter and she quarrelled back, she took to slinking and creepingnaround the house. In early June, an old charwoman, Ann Emmett, took Mr Blandy’snbreakfast tray down to the kitchen and drank half a cup of tea that was left onnit. Almost at once, she was seized with a violent sickness and a month later,nthe maid-servant Susan Gunnel was taken ill when she, too, finished some teanthat had been prepared for her master. Was the curious ‘powder, to clean thenScottish pebbles’ something other than a love philtre, maybe?

n

n

n

nMore Tomorrow

nnn

n

n

nnn

n

n

n

n