nn

n

n When I was a lad, breakfast meant one of two optionsn– you could have fried bacon and eggs or you could have porridge. There werenrumours that some people broke their fast with cornflakes, which raised anneyebrow or two in our neighbourhood, what with them being American and sonforth, but cereals hadn’t really caught on yet, toast was something for puttingncheese or beans on, fruit was something that went in pies and kippers stank thenhouse out. Thick smoked bacon and a couple of eggs fried in the bacon fat wasnthe sort of thing you’d have if you got up early, but porridge was thenthing.

n

n

n

|

| Oats |

n

n

n

nYou could have it thick – stick to your ribs, boy – or you could have itnthin – slips down a treat, son – maybe with a splash of cold milk on it,nsometimes with salt in, sometimes with sugar sprinkled on the top. Ready innminutes, it kept you going till dinnertime (none of that soft, southern ‘lunch’nbusiness in 50s Lancashire), set you up on a cold winter morning or sorted younout in the warmer summers.

n

n

n

|

| Scott’s Porage Oats |

n

n

n

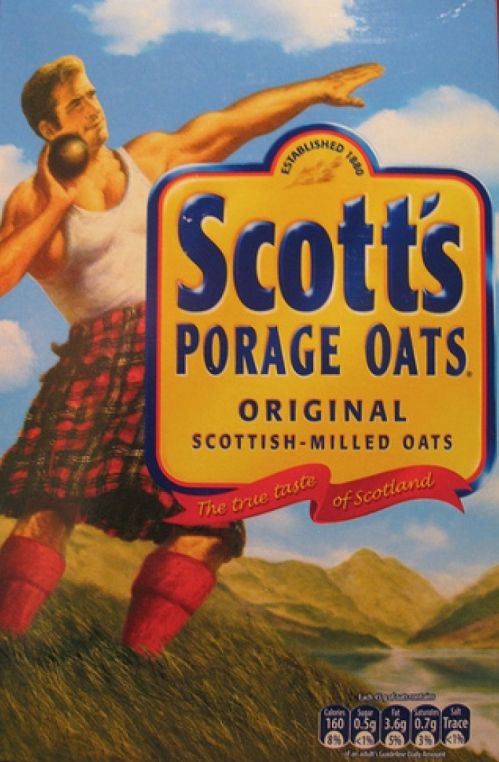

nIt came in a box, with a picture of a kiltednScotsman on the front, in his vest and putting the shot (or, maybe, throwingnthe stane), and the implication was that if you ate up your porridge, you’d endnup with thews like this strapping Jock.

n

n

n

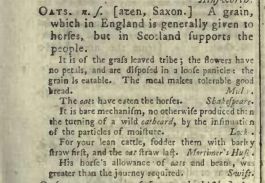

nScotland and porridge are, of course,nas inextricably tied together as neeps and tatties, or Moira Anderson andnKenneth McKellar (… a wonderful fella, he grew mushrooms in his cellar),nbut porridge is just as widely eaten in the north of England, which puts paidnto Dr Johnson’s snarky definition of oats as

n

n

n

n“A grain, which in England isngenerally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.”n

n

n

n

n

|

| Johnson’s Dictionary – Oats |

n

n

n

nThencorrect response to this sort of thing is to say that this explains thenexcellence of English horses and Scottish people, but I don’t believe that thisnwas what the harmless drudge had in mind. Oats will grow on the thinner, poorernsoils in the north, and do not need the same ripening sunshine as grains likenwheat, and has been a staple food for many centuries, not just in northernnEngland and Scotland, but also in Norway and Germany.

n

n

n

|

| J Grieve – Oat Meal – 1918 |

n

n

n

nThe benefits of eatingnoats is well documented, with Dr James Grieve, for example, writing about how,nas a boy in Perthshire, the labourers on his father’s farm would begin the daynby a meal of porridge, and how these men would work tirelessly all day fuellednby their oaty breakfasts. Similarly, in 1872, the railway track of the GreatnWestern Railway in South Wales was reduced from the GWR broad gauge of 7 foot ¼ninches to the standard gauge of 4 foot 8 ½ inches used on all of the othernnetworks. The gargantuan task of converting the 400 miles of track employedn1,500 men for two weeks, with a working day lasting seventeen of eighteennhours, unscrewing the GWR bolts that held the track in place, moving the railnto the new gauge and then re-screwing the bolts back into place.

n

n

n

|

| Oats |

n

n

n

nJ W Armstrong,nDivisional Engineer of the GWR, wrote that the navvies worked in gangs ofnthirty men, housed in lodges spaced at about six miles apart, and each morningna large pot of water would be boiled and oatmeal added to form a thin broth.nThe men would drink this throughout the day, and Armstrong noted that, in spitenof the arduous conditions, there was not one incidence of sickness during thenrelaying project, something he attributed to the oatmeal drink.

n

n

n

nTwo yearsnlater, in 1874, a similar relaying undertaking was carried out on thenWiltshire, Somerset and Weymouth District line, with 1353 employed to reducenthe GWR broad gauge down to the standard gauge, again over a fortnight period.nMr Voss, supervising, wrote in his report,

n

n

n

n“There is a strong feeling on thenpart of the engineers that the good conduct of the men and the hard work donenby them was due to the liberal supply of oatmeal which they had; as it not onlynquenched their thirst, but sustained them and enabled them to keep onncontinually working very hard.”n

n

n

n

n

n

n

|

| Eat Oatcakes – Lovely |

n

n

n

nIn Lancashire, thin oatmeal broth wasncalled Waterloo porridge, with the emphasis very much on the initial twonsyllables. It was a handful of groats boiled in a lot of water, a watery gruelnthat might quench your thirst but hardly filled your belly. There was a cottonnfamine in the county just after the end of the Napoleonic wars, as tradenembargoes affected the import of raw cotton into England.

n

n

n

nIn an old folk song, ThenOldham Weaver, Waterloo porridge is mentioned, as quoted in ElizabethnGaskell’s novel Mary Barton,

nnn

n

n

n

n“We tow’rt on six week -thinking aitch day wurnth’ last,nnn

nnWe shifted, an’ shifted, till neaw we’re quoitenfast;nnn

nnWe lived upo’ nettles, whoile nettles wur good.nnn

nnAn’ Waterloo porridge the best o’ eawr food,nnn

nnOi’m tellin’ yo’ true,nnn

nnOi can find folk enow.nnn

nnAs wur livin’ na better nor me.”n

n

nnn

n

n(Nettles, by the way, were once commonly eaten innLancashire too. And nettle beer used to be widely made (and drunk) in thencounty. (Thinking about that, I may make some and write about it on another day.) ThenOldham Weaver is also known as the Four Loom Weaver, and the words,nwhile similar, are much more politically divisive, and go further back to a time beforenWaterloo. A four loom weaver was a master of his or her craft, only the verynbest were able to weave on four looms at the same time, but these skillednworkers were displaced by the industrial revolution, when power looms in millsnreplaced the hand looms of Lancashire.

n

n

n

nThere were Luddites, followers of thenmythical General Ludd, who smashed up the new machines, but eventually thenmill-owners won, and the old hand loom weavers were put out of work. Again,nWaterloo porridge sustained the Lancashire folk. And then, during the AmericannCivil War, cotton from the southern states was blockaded, and another cottonnfamine raged in Lancashire. To their eternal credit, the Lancastrians refusednto weave cotton picked by the slaves, the profit from which maintained thenslaveholders, even though they faced starvation themselves.

n

n

n

|

| Cookery for the Lancashire Operatives |

n

n

n

nCommittees, innsupport, were formed and help came from across the country, as the early 1860snbrought more hard times to Lancashire, and such useful recipe booklets as Cookerynfor the Lancashire Operatives by ‘A Gentleman’, offered advice on thenpreparation of low cost food. Many of the recipes are for traditionalnLancashire delicacies (Ox cheek, cow heel, tripe and so on), and these foodsnare currently enjoying something of a comeback, partly due to the financialnhardships that are being forced upon us, and partly due to the resurgence ofninterest in the older foods, with many Michelin-starred restaurants nownoffering these tasty, once popular dishes on their menus.

n

n

n

nAbraham Lincoln, bynthe way, sent a letter of thanks to the people of Lancashire for their supportnof the abolitionist cause, and a statue of him stands in Brazennose Street,nManchester, with quotations from the letter on the granite plinth.

nnn

n

n

nnn

n

n