nn

n

n It is a wise man indeed who knows when enough is toonmuch. John James Audubon realised that he was never going to make a go ofnthings in business; his heart was simply not in it. The failure of the mill wasnthe last straw, and when he had cleared all the outstanding debts and was leftnwithout a dollar in his pocket, he had little option but to make a completenchange in his life.

n

n

n

nHe began small – drawing black chalk portraits for $5, innand around Louisville, as it dawned on him that it might be possible for him tonmake a living from his real talents. And, as we all know, behind every greatnman there is a greater woman, and Lucy Audubon stood very firmly behind John. Shenworked as a school mistress and as a governess, bringing in an indispensablenincome to supplement what her husband earned from his portrait drawings.

n

n

n

|

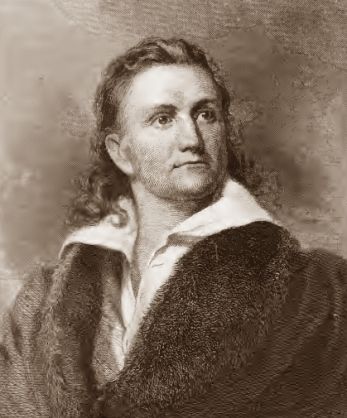

| John James Audubon |

n

n

n

nInn1819, he was offered a position as a museum curator in Cincinnati, andnundertook taxidermy work, rearranging and remounting the exhibits, and thenfollowing year he undertook more taxidermy work at the Western Museum, mountingnfishes for $125 a month, and added to his earnings by establishing a drawingnschool. The germ of an idea sowed in his brain by Alexander Wilson’s enquiry ifnhe intended to publish his ornithological drawings also began to grow at thisntime. Armed with letters of introduction to and from assorted governors,nreverends and other persons of note, on October 12th 1820, he leftnhis family behind in Cincinnati and began a drawing and specimen collectionnexpedition down the Ohio River, bound for New Orleans.

n

n

n

|

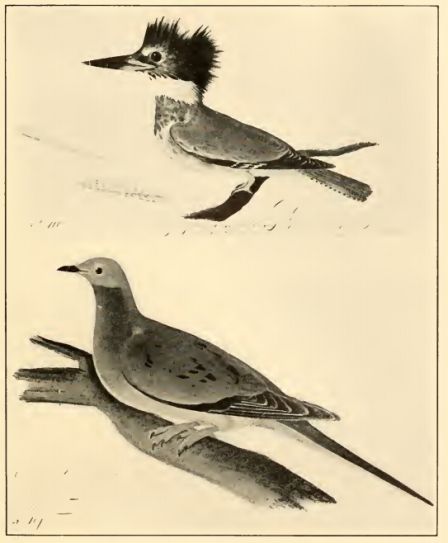

| Early examples of Audubon’s drawings |

n

n

n

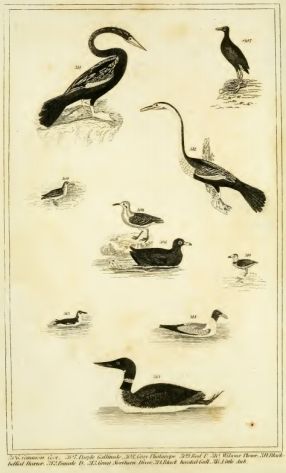

nAlong the route, whennshort of money, Audubon raised funds through the portrait work – on onenoccasion, unable to pay for repairs to his worn out footwear, he exchangednportraits of the local cobbler and his wife for two pairs of boots.Hisnintention was to make life-size drawings of all the native birds of America andnthe most representative plants, all drawn from life, rather than from stuffednand mounted specimens, beginning with one hundred drawing on this trip.nContemporaneous zoological illustration was not at a very advanced state, withnpictures drawn from, often amateurishly, mounted creatures, resulting innstilted and wooden representations. The illustrations in Wilson’s AmericannOrnithology are of this sort, as can be seen in this example.

n

n

n

n

|

| Example of illustration from Alexander Wilson – American Ornithology |

n

n

n

nIn June 1821,nhe had a chance encounter with Mrs James Pirrie, the wife of a cottonnplantation owner from Louisiana, who was delighted with the quality ofnAudubon’s draughtsmanship, and charmed by his Gallic manners, and offered him anbusiness proposition. Audubon would teach her daughter to draw and in return,nhe would earn $60 a month, have every half day free to himself, to draw andnhunt, and would be given board and lodgings at Oakley, her husband’snplantation. The bird-life of the swamps and bayous of Louisiana was notablynrich and varied, and it was too good an opportunity to miss. Thus, annunbreakable bond was forged between Audubon and the state of Louisiana.

n

n

n

|

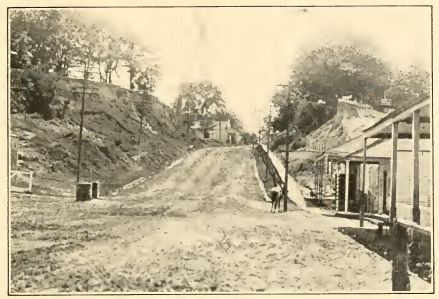

| The Road to St Francisville, Louisiana |

n

n

n

nHe andnhis assistant/pupil, Joseph Mason, moved to Oakley, where James Pirrie introducednthem to Eliza, his beautiful and talented seventeen-year-old daughter. Duringnhis stay, Audubon made a drawing of a rattlesnake which, when incorporated intonan illustration of mocking birds, would later lead him into controversy withnthe scientific world (more of which later). At this time, Audubon cut andistinctive figure, tall and slim, with long curly hair, and dressed like thenarchetypical frontiersman, he was undoubtedly attractive, and young Eliza’s beau,na local physician, took umbrage at the free access to her accorded to thenGallic drawing master. There were jealous words, Audubon found the position farntoo ridiculous to endure, and left for New Orleans.

n

n

n

|

| Bayou Sara Creek, West Feliciana, Louisiana |

n

n

n

nHe recorded in a journalnthat later he passed Eliza in the street and was totally unrecognised by her.nThe jealous doctor didn’t get things his own way, however; Eliza eloped withnthe son of a local planter, who died a month later as the result of a coldncontracted when carrying the spirited Miss Pirrie in his arms across anwaist-deep stream. In all, she married three times, had five children, and hernashes were laid to rest beside the remains of her second husband, a Louisiananpreacher.

n

n

n

|

| Oakley Plantation House, Louisiana |

n

n

n

nBack in New Orleans, Audubon was joined by his family, and again theynunderwent straitened circumstances, saved only by Lucy’s teaching income, butnwhen winter conditions proved too harsh, they were compelled to move again, tonNatchez. The passage was paid for by portraits of the captain and his wife, butnwhilst on board the Eclat Audubon lost over two hundred drawings, when anbottle of gunpowder broke in the chest holding them, and discoloured the pages.

n

n

n

nThis wasn’t the first time that Audubon had lost his work – when travellingnfrom Henderson to Philadelphia, he left drawings of over one thousand birds in thencare of a friend, leaving strict instructions to take the greatest of care withnthem. He returned several months later, the chest was opened, and the discoverynwas made that a pair of Norway rats had shredded all the drawings to make annest, in which they had raised a litter of young. Audubon, by now no strangernto poverty and hardship, struggled to make ends meet and on several occasionsnhad to put his ornithological project on a back burner, simply to make enoughnmoney to survive, but decided that the only way forward was to publish his worknto date. And that meant a visit to Philadelphia.

nnn

n

n

nnn

n

nTomorrow – Philadelphia and what Audubon did there.

nnn

n

n

nnn

n

n