Imagine a time when the Tory government was not the dominant force it is today. In the early 1790s, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger faced significant opposition from radicals who were unhappy with his policies. In a bid to silence dissent, Pitt’s administration enacted laws that would redefine treason and suppress political opposition.

Key Points

This fascinating chapter in British history reveals the lengths to which a government might go to maintain control and the brave individuals who dared to challenge it.

Rise of Repressive Legislation

In 1351, an Act had defined seven offenses as high treason, including the grave crime of “imagining the King’s death,” punishable by hanging, drawing, and quartering. Fast forward to Pitt’s era, and we see a similar atmosphere of fear and repression. The government passed two significant pieces of legislation known as The Treasonable and Seditious Practices Act and The Seditious Meetings Act—collectively referred to as ‘The Two Acts.’ These laws expanded the definition of treason to include actions that brought the Crown, the Constitution, or the Government into contempt.

One of the most vocal opponents of these acts was the London Corresponding Society for Reform of Parliamentary Representation (LCS). This group advocated for social reforms, including extending voting rights to more working-class individuals. They published pamphlets criticizing the government, which were viewed by authorities as treasonous. Among the writers was Dr. James Parkinson, who used the pseudonym ‘Old Hubert’ for his works, including the notable pamphlet titled Revolutions without Bloodshed.

Pop-Gun Plot: A Government Conspiracy?

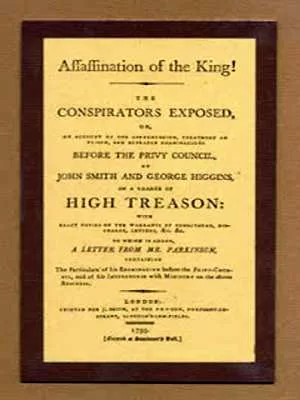

In October 1794, Dr. Parkinson found himself in a precarious position when he was summoned before Pitt and the Privy Council to explain his alleged involvement in a plot to assassinate King George III. This supposed conspiracy, known as the Pop-Gun Plot, involved radicals who allegedly planned to shoot the King with a poisoned dart fired from an air gun. However, many historians believe this plot was likely a fabrication by the government to justify stricter laws and rally public support against dissenters.

Dr. Parkinson and several other LCS members were suspected of involvement in this plot. Although they were imprisoned, there was insufficient evidence to convict them, and they were eventually released without charges. The government’s obsession with air guns as a threat to the monarchy was further illustrated when, on October 29, 1795, a projectile—likely a pebble—was thrown at the King’s carriage, leading to exaggerated claims of an air gun attack.

Political Climate and Public Dissent

The political climate of the time was charged with tension. As King George III traveled back to the Palace after the alleged air gun incident, his carriage was attacked by a mob shouting anti-war slogans and demanding peace. The crowd’s anger was palpable, with chants of “No Pitt, No War, Bread, Bread, Peace, Peace!” echoing through the streets. Although five individuals were arrested, no trials followed, and rumors circulated that government agents had incited the mob. Such tactics raise questions about the lengths to which authorities would go to suppress dissent—echoing concerns that resonate even today.

Shift in Focus: From Politics to Medicine and Geology

Perhaps fearing the repercussions of sedition, Dr. Parkinson shifted his focus away from political activism. He dedicated more time to his medical career and his burgeoning interest in paleontology. In 1804, he published The Villager’s Friend and Physician, a work aimed at promoting preventative medicine to the general public.

As a surgeon, Parkinson made significant contributions to medical literature, including studies on gout, appendicitis, and the condition that would later bear his name—Parkinson’s Disease. His work in medicine was complemented by his passion for geology. Frustrated by the lack of descriptive literature on fossils, he authored a three-volume series titled Organic Remains of a Former World, published between 1804 and 1811. This work was highly regarded and influenced other prominent geologists of the time.

Birth of the Geological Society

Parkinson was also one of the founding members of the Geological Society of London, which held its first meeting in 1807 and received its Royal Charter in 1825. The popularity of geology surged among gentlemen scholars in the early nineteenth century, with fossil hunting becoming a respectable pastime for both men and women. The society’s membership at one point threatened to surpass that of the Royal Society, highlighting the growing interest in the natural sciences.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Change

The early 1790s were a tumultuous time in British history, marked by political repression and the struggle for reform. Figures like Dr. James Parkinson exemplified the courage to challenge authority, even in the face of severe consequences. His transition from political activism to medicine and geology illustrates the resilience of the human spirit and the enduring quest for knowledge.

As we reflect on this period, we are reminded of the importance of dissent in shaping our society. The legacy of those who stood up against oppressive regimes continues to inspire movements for change today. In a world where political tensions still exist, the lessons from history remain relevant, urging us to value our rights and the voices of those who dare to speak out.