The Gregorian Calendar Shift: Separating Fact from Fiction

The Battle of Sedgemoor, fought on July 6th, 1685 (Old Style), is a pivotal moment in British history. But what does “Old Style” mean? It refers to the Julian calendar, which was replaced by the Gregorian calendar in 1752. This change sparked myths, including the infamous “Give us back our eleven days” riots. Let’s explore the truth behind the calendar reform and its impact.

The Julian Calendar: A Brief History

The Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BCE, was a significant improvement over earlier Roman calendars. It divided the year into 365 days, with a leap year every four years. However, it had a small error: it overestimated the solar year by about 11 minutes.

Over centuries, this discrepancy added up. By the 16th century, the calendar was 10 days out of sync with the solar year. This misalignment affected religious observances, particularly Easter, which is tied to the spring equinox.

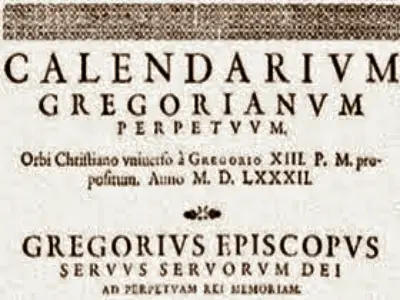

The Gregorian Reform: A Solution to the Problem

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar to correct the Julian calendar’s inaccuracies. The reform involved:

- Skipping 10 days to realign the calendar with the solar year.

- Adjusting the leap year rule to exclude centurial years not divisible by 400.

Catholic countries like Spain, Portugal, and Italy adopted the new calendar immediately. Protestant countries, including Britain, resisted the change due to its association with the Catholic Church.

Britain’s Adoption of the Gregorian Calendar

Britain finally adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752. By then, the discrepancy had grown to 11 days. To correct this, September 2nd, 1752, was followed by September 14th.

Contrary to popular belief, this change did not spark riots. The myth of the “eleven days” riots likely originated from political satire and later misinterpretations.

The Myth of the Riots

The idea that people rioted over the lost days is a persistent myth. It gained traction from two sources:

- William Hogarth’s Satire: In his 1755 painting An Election Entertainment, Hogarth depicted a placard reading, “Give us our eleven days.” This was a satirical jab at political corruption, not a reflection of public sentiment.

- Misinterpreted Historical Accounts: Writers like Archdeacon William Coxe later embellished the story, claiming widespread public outrage.

In reality, there is no contemporary evidence of such riots. The transition was smooth, with only minor complaints from bankers adjusting to the shorter month.

Why the Myth Persists

The “eleven days” myth endures because it fits a familiar narrative: people resisting change due to ignorance or superstition. It’s often used to mock past generations, much like the myth that people once believed the Earth was flat.

However, this myth overlooks the practical reasons for the calendar reform and the public’s general acceptance of it.

The Impact of the Calendar Reform

The adoption of the Gregorian calendar had several important effects:

- Religious Observances: It ensured that Easter and other movable feasts were celebrated at the correct times.

- International Consistency: It aligned Britain’s calendar with those of other European countries, simplifying trade and communication.

- Scientific Accuracy: It brought the calendar in line with astronomical observations, improving timekeeping.

Lessons from the Calendar Reform

The Gregorian calendar reform teaches us two key lessons:

- Change Takes Time: Even necessary reforms can face resistance, especially when tied to political or religious controversies.

- Myths Can Outlast Facts: Stories like the “eleven days” riots persist because they are compelling, even if they are untrue.

Conclusion: Separating Fact from Fiction

The shift from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar was a significant moment in history. While it inspired myths like the “eleven days” riots, the reality was far less dramatic. The reform was a practical solution to a long-standing problem, and its adoption marked a step forward in timekeeping and international cooperation.

Next time you hear about the “lost eleven days,” remember: it’s a myth, not history.