Miss Mary Henrietta Kingsley: The name might not immediately ring a bell, but this remarkable woman defied the expectations of Victorian society and became one of the most fearless explorers of her time.

Born in 1862 into a typical Victorian upbringing, Kingsley led a life that was anything but typical. Her adventures in Africa challenged the norms of her era, and her writings provided a unique perspective on the continent and its people.

An Unconventional Start: Early Life and Family

Mary Kingsley was conceived out of wedlock, with her parents marrying just four days before her birth. Her father, George Kingsley, was a doctor and traveler, while her mother, Mary, was a former cockney servant.

Despite being born into a family with a strong academic background, Mary received little formal education—a sharp contrast to her brother Charley, who attended Christ’s College, Cambridge, to study law. Instead, Mary was expected to stay home and care for her frequently ill parents, an arrangement that would shape her early years.

Mary’s life took a significant turn in 1892 when both of her parents passed away within months of each other. At the age of 29, Mary found herself with newfound freedom and an annual allowance of £500 from her brother, who had decided to travel to China. Rather than conform to societal expectations and settle down, Mary chose to embark on a journey to Africa—a continent she had long been fascinated by, largely due to her father’s unfinished ethnographic work.

The African Expeditions: A Victorian Spinster in the Jungle

In August 1893, Mary Kingsley arrived in Sierra Leone, marking the beginning of her first African expedition. Unlike other Victorian women who might have sought the safety of home, Mary was determined to explore the uncharted territories of West Africa. Her wardrobe—a crisp white blouse, thick black woolen skirt, and a black sealskin hat—might have seemed more suited to the streets of London than the African jungle, but she was unapologetic about her choice of attire, stating, “… you have no right to go about in Africa in things you would be ashamed to be seen in at home.”

During her travels, Mary faced countless dangers, from crocodile encounters to falling into animal traps. In one particularly harrowing incident, she found herself in a mangrove swamp, battling a crocodile that had latched onto her canoe. With quick thinking and a firm hand, she managed to fend off the beast by striking it on the snout with a paddle.

Her account of the event is laced with her characteristic wit: “I had to retire to the bows, to keep the balance right, and fetch him a clip on the snout with a paddle… I should think that crocodile was eight feet long; but don’t go and say I measured him.”

Mary’s adventures also included navigating through the dense jungle, where she fell into a spike-filled animal trap. Her thick skirt, which might have seemed impractical to some, saved her from serious injury: “It is at these times you realise the blessing of a good thick skirt… had I adopted masculine garments, I should have been spiked to the bone, and done for.” Her Victorian attire, often ridiculed, proved to be an unexpected advantage in such perilous situations.

A Different Perspective: Writings and Critique of Imperialism

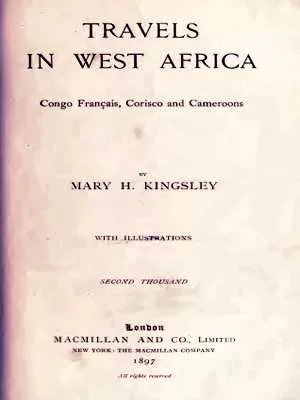

After returning to England, Mary Kingsley penned two influential books, Travels in West Africa and West African Studies. These works not only detailed her extraordinary adventures but also offered a critique of British imperialism and the prevailing attitudes towards Africans. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Kingsley did not view the African people as “savages” or “silly children.” Instead, she argued that the black man “… is no more an undeveloped white man than a rabbit is an undeveloped hare.”

Her views extended to a critique of the Church of England and Protestant missionaries, whom she accused of portraying Africans as “… drunken idiots” to excuse their own failures. Kingsley’s writings were groundbreaking in that they presented a more nuanced view of African societies, one that recognized their complexity and humanity.

Not a Feminist, But a Fearless Woman

While some have tried to paint Mary Kingsley as a feminist icon, she herself did not identify with the movement. She opposed the idea of women’s suffrage, arguing that “… the House of Commons is already packed with uninformed men and the addition of a mass of even less well-informed women would only make matters worse.” Kingsley believed that women were unfit for parliament and that parliament was unfit for them—a viewpoint that might seem contradictory given her own trailblazing life.

Despite her rejection of feminism, Kingsley’s actions spoke volumes about her belief in the capabilities of women. She ventured into territories that were considered dangerous even for men, challenging the Victorian ideals of what a woman could or should do.

The Final Chapter: Nursing in the Boer War

As the Second Boer War broke out in 1899, Mary Kingsley once again defied expectations. She traveled to South Africa to serve as a nurse, tending to Boer prisoners in the Cape. Even in this role, she remained undaunted by the dangers, with the famous writer Rudyard Kipling noting, “Being human, she must have feared some things, but one never arrived at what they were.”

Tragically, Mary Kingsley’s life was cut short when she contracted typhoid fever and died on June 3, 1900, at the age of 37. In keeping with her adventurous spirit, she requested to be buried at sea. However, in a final twist of fate, her coffin was not weighted properly and floated on the surface until a sailor attached an anchor to send it to its watery grave.

Legacy of an Unconventional Explorer

Mary Kingsley’s life and adventures have inspired countless readers and historians. Her writings offer a unique glimpse into a time when Africa was still a mystery to the Western world, and her critiques of imperialism and gender roles remain relevant today. Kingsley’s legacy is not just that of a fearless explorer, but of a woman who refused to be confined by the limitations of her time.

For those intrigued by her story, her books Travels in West Africa and West African Studies are a must-read, offering not just tales of adventure, but also thoughtful observations on the cultures she encountered. Kingsley’s life serves as a reminder that true courage is not about the absence of fear, but about facing it head-on, no matter the odds.