In 1327, the town of Bury St. Edmunds witnessed an uprising that shook the foundations of the powerful Benedictine Abbey. This dramatic event, known as the “Great Riot,” was fueled by the long-standing grievances of the townsfolk against the Abbey’s oppressive rule.

The riot saw angry citizens storm the Abbey, assault the monks, and loot its treasures. Among the most intriguing figures in this story is Ralph le Smeremongere, a candle maker whose profession ties him to a rich tapestry of medieval folklore.

The Great Riot of Bury St. Edmunds

The Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds was one of the most powerful religious institutions in medieval England. However, its wealth and influence came at a price. The townspeople, who lived under the Abbey’s jurisdiction, were subject to heavy taxes, harsh punishments, and countless other abuses. By 1327, their anger had reached a boiling point.

While the Abbot was away in London, the townsfolk seized the opportunity to act. Led by six prominent citizens, including Ralph le Smeremongere, the rebels attacked the Abbey, kidnapping the Prior and twelve monks. They forced the monks to sign a document indebting the Abbey to a staggering £10,000 and absolving the townspeople of all debts and trespasses.

The rioters also looted the Abbey, carrying away gold and silver chalices, books, vestments, and other valuables.

Ralph le Smeremongere: The Candle Maker

Among the leaders of the Great Riot was Ralph le Smeremongere, a man whose name offers a glimpse into his profession. The term “smeremongere” comes from the Old English word “smere,” meaning fat, grease, or tallow. A smeremongere, therefore, was a candle maker, a vital trade in an era before electric lighting.

Candles were essential for both domestic use and religious ceremonies in medieval times. The process of candle making involved melting animal fat or beeswax, which was then poured into molds or dipped repeatedly to form candles. Candle makers like Ralph played a crucial role in their communities, providing light in the dark and supplying candles for churches and homes alike.

Medieval Candle Folklore

The ancient craft of candle making is steeped in folklore and superstition. In medieval England, candles were more than just sources of light; they were believed to possess magical properties. For instance, it was said that a young woman could test her lover’s fidelity by pushing a needle through a candle and lighting it. If the needle remained in the wick, her lover was true; if it fell out, he was unfaithful.

Another superstition warned against lighting three candles with the same match, as this was believed to bring bad luck. In Lancashire, there was a tradition known as “leeting” or “layting” witches, in which people would carry boughs of rowan and bay along with a lighted candle up Pendle Hill on Halloween night. If the candle stayed lit between eleven and midnight, it was thought to protect the bearer from witchcraft for the coming year.

The Grisly Legend of the Hand of Glory

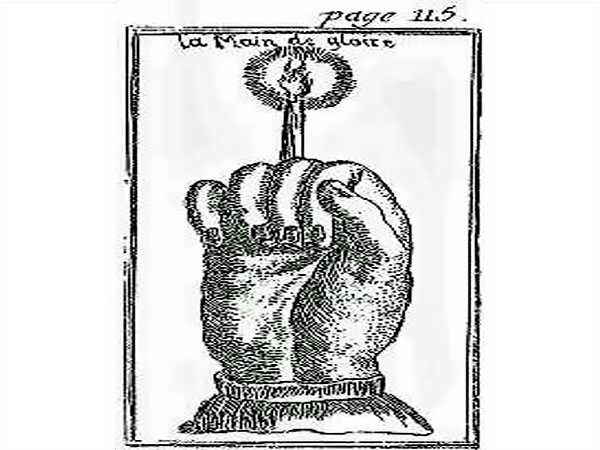

One of the most macabre and fascinating aspects of medieval candle folklore is the legend of the Hand of Glory. This gruesome artifact was said to be the hand of a hanged man, which had been dried and preserved, with a candle made from the fat of a hanged criminal placed in its grip. When lit, the Hand of Glory was believed to possess terrifying powers. It could render sleepers in a house unconscious, open any lock, and make the holder invisible. The only way to extinguish its flame was with milk.

This eerie legend likely arose from a mistranslation of the French term “la Main de Glorie,” which referred to a mandrake root, not a human hand. The mandrake plant itself was steeped in mythology, believed to scream when uprooted, with its cries capable of killing anyone who heard them. The connection between the mandrake and the Hand of Glory adds a chilling layer to the folklore surrounding medieval candle making.

The Legacy of the Great Riot

The Great Riot of 1327 was a turning point in the history of Bury St. Edmunds. While the Abbey eventually regained control, the riot exposed the deep-seated resentment and anger of the townspeople. It also highlighted the significance of seemingly ordinary figures like Ralph le Smeremongere, whose involvement in the rebellion linked him to both the political turmoil of the time and the rich traditions of medieval craftsmanship.

Today, the legend of the Hand of Glory and other candle-related folklore serve as reminders of the dark and mysterious beliefs that shaped the lives of medieval people. As for Bury St. Edmunds, the memory of the Great Riot remains a testament to the power of collective action in the face of oppression, a story that continues to intrigue historians and capture the imagination of those who delve into England’s medieval past.